Photos and text by Collin Mayfield. Opinions expressed are the author’s own and do not reflect Atlas News.

PORT-AU-PRINCE, Haiti. Criminal factions control most of the capital city, and as different gangs fight to expand their respective territories, the local populace suffers. The violence persists at a time that Haiti also endures food insecurity, extreme poverty, fuel shortages and a resurgence of cholera. Crises compound other crises, and the overlapping horrors have caused mass exodus from the country.

Haiti is constantly wracked by crisis – natural and political. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the capital city Port-au-Prince. Flying in, it looks gorgeous. Luscious green mountains surround a vibrantly-painted coastal, Caribbean city. From above it appears an idyllic vacation spot, and some parts of Haiti are – but not Port-au-Prince.

Haiti and its capital lack a properly functioning government. Buildings lie in ruin – destroyed by earthquakes and neglect. Protest has been ongoing since 2018; tire fires are an almost daily occurrence. Nearly half of Haitians face acute hunger, including over 20,000 famished souls in Port-au-Prince. Cholera’s returned, exacerbating the dreadful situation.

Parts of the city are defined by knee-high piles of garbage. There’s so much that my fixer and I had to walk through rotting rubbish or drive our motorcycle through it; a moto is the best way to traverse the capital. The city’s trash disposal method is to bulldoze and burn, contributing to the poor air quality. The seashore is covered in trash and excrement, but it’s too dangerous to visit anyway. Gangs control the coastline and most of Port-au-Prince.

Brazen violence holds the city hostage. Haiti’s capital is saturated with dozens of major gangs and hundreds of smaller ones. An estimated 60-75% of the city is gang-held. Their territories surround Port-au-Prince, and thus control city access. Former Prime Minister Laurent Lamothe, despite allegations of gang connections himself, called Haiti’s abysmal security situation ‘urban guerilla warfare,’ and that’s no exaggeration. Port-au-Prince residents struggle to survive in the constant gang war.

Per the UN, over 1000 people have been killed in gang fighting in 2022. Different factions are actively competing for influence and territorial hold over the city. The Haitian National Police (HNP) are unmotivated and under-equipped to quell gang fighting, if police officers themselves aren’t directly complicit.

Initially, I tried to count all the gunshots I heard, whether around town or at my rental, but I quickly lost track. Shooting happened throughout the day, and particularly at night. Sometimes it was two or three shots. But other times it was dozens, from different areas and their sounds overlapping – indicative of a fight. I heard hundreds of gunshots over my few weeks in Port-au-Prince.

Gangs are mostly financed by kidnappings, alongside extortion and drug trafficking. This gives gang-filled Port-au-Prince the world’s highest per capita kidnapping rate, but the entire island faces abductions. Most victims are middle class, and ransoms average about $20,000. Over 1000 people were kidnapped in 2022, and many remain in captivity.

Gangs find most prey in the morning rush, from about 6 to 9 AM, but victims are often seized in the evening rush from 3 to 6 PM as well. Very few people go out at night. When riding the motorcycle after dark, I only saw dozens to hundreds, depending on how far we went, out of the metropolitan area’s over 3 million residents.

One gang will invade the territory of another. Invading gangsters try killing any rival they see, which translates to killing any men unlucky enough to live there. Rape is a weapon in gang arsenals. Women and girls are sexually assaulted by gangbangers for living in a rival’s territory. Some victims are sexually assaulted in front of their children, while others are made to watch their loved ones be murdered before being raped themselves.

These atrocities are documented by the National Network for the Defense of Human Rights (RNDDH), the nation’s leading human rights group. Executive Director Pierre Esperance met me for an interview where we discussed the state of the country.

“Theyre were about 60 women who were raped – and it was a collective [gang] rape. And then those people [victims], they tried to get support from the state. They don’t receive any support. The internally displaced don’t have any place to go,” Esperance explained.

To increase safety, institutions that can afford to hire private security. Grocery stores, fancy restaurants, nice hotels and even a hookah bar I patroned are maintained by private security with pistols or pump action shotguns. Middle and upper-class homes are encircled with walls topped by barbed wire, and these relatively nice areas stand in stark contrast to the sprawling slums.

Some churches are armed too. With my rental hosts, I attended a church service at the Quisqueya Chapel. While most of the congregation is Haitian, many parishioners are foreigners. Aid workers, missionaries, diplomatic and NGO personnel worship at Quisqueya.

While most people kidnapped are Haitians, foreigners are a preferred target because of their higher ransoms. In 2021, the 400 Mawozo gang famously kidnapped 17 North American missionaries. The gang demanded $17 million ransom before all 17 captives were released at an undisclosed, lesser price.

At Quisqueya, a security guard named Maurice protected the congregation. Armed with a pump action shotgun, he manned the steel door at the entrance of Quisqueya’s grounds. He let parishioners in and kept kidnappers out. Yet his pump action shotgun is little match to a gang member’s semi, or sometimes fully, automatic rifle.

Presidential Assassination and Power in Port-au-Prince

In July 2021, Haiti’s president Jovenel Moïse was gunned-down in his private residence. Police subsequently arrested about 20 Colombian mercenaries. Over a year later questions still abound. None of the Colombians, or anyone else, were tried for the murder. Judges don’t want the case; it’s already on its fifth judge. Everyone has an idea who was responsible for the killing, but most Haitians I met shared the same general notion – the bourgeoisie had Moïse killed for threatening their interests.

President Moïse was replaced by the unelected Prime Minister, Ariel Henry, who is allowed to rule without a president until the next election. But what started as a provisional government is here to stay. Henry disbanded the Provisional Electoral Council (CEP) and suspended elections. Even before Moïse’s assassination, the date for elections was a point of contention, and now more so.

Henry’s administration says there will be “free and democratic elections” at some point in 2023, with a new government supposedly coming in 2024.

Now, there’s a power vacuum in Port-au-Prince, and at least 200 gangs have expanded their control in the wake of Moïse’s murder. At best, the fighting is tolerated by the government. At worst, it’s state-sponsored.

Henry is fiercely unpopular, electoral hijinks aside. Some suspect his involvement in Moïse’s murder, and when a chief prosecutor attempted to charge the PM in connection to the killing, Henry had him dismissed. The PM also ended fuel subsidies last September, increasing prices and revamping already ongoing protests. Haiti’s most powerful gang, G9, responded to Henry’s subsidy removal by blockading the Varraux fuel terminal. It’s Haiti’s largest, and G9’s blockade starved the nation of petrol. Even government vehicles struggled to get fuel.

Human rights groups, such as the RNDDH, allege that the gangs are intrinsically linked to self-serving politicians and government officials. The government, human rights activists say, is directly responsible for the gangsterization of the country.

The Haitian authorities, explained RNDDH director Pierre Esperance, “provide guns and munitions to the gangs to remain to stay in power [sic]. And the authorities are behind the gangs!”

Politically affiliated gang-militias, often with quasi-official powers, have been a regular element of Haitian politics throughout the country’s history. Port-au-Prince has seen gang activity for decades, but beginning in the 2010s, gangs started becoming more politicized. Politicians funded their preferred groups, and the gangs acted with more and more impunity. This applies to both incumbents and their opposition. All sides support their respective gangs, and the gangs return the favor by securing votes and attacking political opponents.

This politicization was especially prevalent under Moïse (allegedly), and factions like G9 and its break-off G-Pep have increased the violence to previously unseen levels. Some gang leaders have attempted to present themselves as community leaders rather than crime bosses, and a few have limited support in territories they control.

“The gangs – they have a lot of power,” Esperance explained. “They are everywhere … the authorities, they don’t protect Haitian people. They protect the gangs.”

Now, criminal groups are more powerful than the state. Even PM Henry struggles to traverse between his home and office because gangs control much of the area. I saw Henry travel through the city center once, from a distance. He rode in a convoy of armored vehicles and police Toyotas to dissuade attacks from gangsters.

There are frontlines, as in other armed conflicts, where the territory of one group collides with another. Like other warzones, buildings lie abandoned in ruin permeated by bullets or scorched from fire. Port-au-Prince is filled with these frontlines, and some 96,000 people are displaced by the gang fighting in the capital alone.

Now, former and current members of government are calling the international community to act. They want an anti-gang task force, but most of the Haitian public would view any military or police intervention as foreign powers backing the unelected Henry.

The United Nations already came to Haiti in 2004 after a coup forced President Jean-Bertrand Aristide from office. Over 5000 UN personnel participated in the mission. The military force fought the gangs before the UN reduced their operations and troop numbers in 2017, finally leaving Haiti in 2019.

Aid groups like the RNDDH don’t view intervention as a viable solution; foreign intervention could cause more bloodshed. Besides, the UN’s previously failed interventions saw rampant sexual abuse committed by ‘peacekeepers’ – along with other abuses. Hundreds of children are thought to have been fathered by impune UN personnel. Sri Lanken peacekeepers were even implicated in a child sex ring with victims as young as 12.

The United Nations also brought cholera into Haiti, killing at least 10,000 in their clumsy mistake. The UN didn’t adequately check Nepalese peacekeepers who came to bolster the existing mission after the 2010 earthquake. They begrudgingly acknowledged their fault, but did not take responsibility.

The Top Gangster

One of Port-au-Prince’s most prominent gang leaders is a former policeman named Jimmy Chérizier – better known as Barbecue. There’s debate over where he’s gotten his moniker. He claims it comes from working with his street-vending mother selling chicken. Barbecue’s critics say it’s because he sets people on fire.

Barbecue leads a coalition of gangs called the Revolutionary Forces of the G9 Family and Allies, or G9. Founded in 2020, G9 is a collection of about 95 smaller gangs in Port-au-Prince. Their grasp extends through the center of the capital to the northern and southern entryways. They hold territory in Martissant, Village de Dieu, Bel Air, Grande Ravine, Cité Soleil and their likely stronghold of Delmas, where I stayed. G9 can separate the capital from the rest of the country at a whim.

Barbecue is considered to be one of, if not the most, powerful gang leaders in Haiti. He has powerful allies too – Barbecue aligned G9 with the slain Moïse’s Tèt Kale Party (PHTK).

Barbecue is widely believed to have ordered several massacres from 2017 to now, and many occurred while Chérizier was still a police officer. The most infamous was the 2018 La Saline massacre where 71 people were killed and 400 homes were burned.

The neighborhood was a bastion for the former president’s opposition and a frequent site of anti-government protests. Survivors maintain that the massacre was political. The neighborhood was a threat to Moïse’s power.

Witnesses claim that a police truck, with uniformed officers, arrived in La Saline before opening fire on residents. Meanwhile, gang members either hacked residents to death or simply shot them. Corpses were found mixed into animal feed at a La Saline pig farm.

Barbecue was fired from the Haitian National Police the next month over his alleged perpetration of the La Saline massacre, and the United States later sanctioned him and two officials in Moïse’s government for their alleged involvement.

But allegedly, as long as G9 maintained peace in its territory, the Moïse government didn’t prosecute gang members, and police didn’t intervene in killings. In many instances, police have been near massacres allegedly perpetrated by G9 but failed to respond – not receiving any orders from superiors.

Massacres in Cité Soleil and Bel Air saw no police reports filed, prosecutors heard nothing from surviving victims, and police equipment was suspiciously present, per an RNDDH report. Many victims were burnt to a crisp. Again, human rights activists allege the deceased Moïse ordered the killing of dissidents.

Despite frequent allegations, Barbecue denies being involved in any massacres or human rights violations. He’s instead an active community leader in an armed struggle against corruption and impunity in government. Barbecue says G9 doesn’t kidnap and he routinely condemns the abductions – despite allegations to the contrary.

He wears a black beret and styles himself as a revolutionary, frequently comparing himself to heroes of the revolution like Jean-Jacques Dessaline. Signs and murals of Che Guevara dot G9 territory.

After his death Moïse became a martyr, and Barbecue led over 1000 supporters in a march through Delmas while demanding that the killers face justice.

Since then Barbecue has only gotten more bold, and he’s against the popularly despised Henry. On Oct. 17, 2021, G9 members fired automatic weapons at the Prime Minister while he was laying a memorial wreath at the monument to self-proclaimed Emperor Dessaline. It was the 215 anniversary of the Emperor’s assassination. The monument was in gang-held Pont Rouge, Port-au-Prince. Henry and his delegation ran from the gunfire. Then, dressed in a white suit, Barbecue walked up to the Emperor’s monument and placed a floral arrangement at the base.

Starting in mid-September, G9 blockaded the Verreaux fuel terminal. This is Port-au-Prince’s main petrol depot; it holds about 800,000 gallons of kerosene and about 10 million gallons of gasoline and diesel. The siege exacerbated the already existing fuel shortage. Gas stations closed. Taxis stopped driving. Many businesses had to cut hours because of a lack of fuel and patrons. It was paralyzing. Even government vehicles were starved of gasoline.

G9 refused to lift the blockade until Henry resigned as prime minister, but a month into the blockade, Henry requested a foreign military intervention. Barbecue then backtracked on Henry’s resignation but demanded amnesty for himself and his compatriots – along with positions in government.

Shortly before I arrived in November, Haitian National Police routed G9 and a UN resolution targeted Barbecue with more sanctions. Chérizier is under a travel ban, assets freeze and arms embargo.

The blockade ended, and fuel distribution resumed.

But there’s still the perpetual fuel shortage and sporadic fighting near Verreaux pauses fuel distribution. My fixer and I waited in long queues to fill up the moto.

Two other Haitian politicians, Joseph Lambert, sitting President of the Haitian Senate, and Youri Latortue, a former senator, were recently sanctioned by the United States and Canada over allegedly using their positions to aid gangs in international drug trafficking.

Barbecue initially accepted my request for an interview through my intermediary, although he continually pushed back the date before ultimately canceling on me. Although he’s the most media-friendly gang leader, sometimes holding press conferences, he’s been quiet since his UN sanctions this past October.

Corrupt, Incompetent Police

It’s an accepted fact that Haiti is plagued with corruption, and nowhere is this more obvious than in the Port-au-Prince police. Some police have gang affiliations and provide groups with material or intelligence aid. There’s even a gang specific to police – Baz Pilate. It’s made of current and former police, and they control some territory in downtown, though their holdings are insignificant compared to other gangs.

It’s clear why some police are corrupt; most make about $300 a month so gang-affiliation helps pad their pockets. Others are unfortunate enough to live in gang territory, so they’re easily coerced for the sake of keeping themselves and their families alive.

The US backs the unelected Henry administration, and has subsequently pledged more aid for the police. In early 2022, the State Department provided $48 million to support Haitian law enforcement and sent an unspecified number of police advisors from the U.S. Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement.

In October, the United States and Canada provided the Haitian National Police with armored vehicles, mostly MRAPs (Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected vehicle), for an undisclosed price. The HNP lost control of one of these vehicles the next month. When a police station was overrun by gang members in November, the HNP sent multiple armored vehicles to the site. While police claim one MRAP broke down, witnesses claim the vehicle got stuck in a sand trap. The police abandoned the vehicle while it was being hit with molotovs. As police fled, the militants shot in the air as they celebrated their new prize. The MRAP was later recaptured.

A Cathedral in Ruins, Blood in the Street

Bullet-riddled buildings are abandoned around the city center – destroyed from repetitive earthquakes, neglect and gang war. The ruins of the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Assumption, destroyed in the 2010 earthquake, are in a particularly bad part of downtown. Coming up to the church, I immediately met a gang-affiliated man who ensured that it was okay to approach the cathedral. Its ruins are fenced off and abandoned, and we heard gun fire not far down Rue St Laurent.

After a few minutes we were back on the motorcycle. Racing south through traffic, my fixer maneuvered around mounds of trash and past an armored police vehicle. He drove south from downtown, and up the mountain into the Savane Pistache neighborhood. Fighting had been heavy there since the week before.

Bullets rained in Savane Pistache, where the Gran Ravin gang is actively trying to expand territory. In the several days before my visit, the gang was fighting to annex new land. Gran Ravin was burning houses and cars to capture territory, alongside using conventional gunfire. Local woman Cathiana Pierre was burned alive in her home while several other civilians were shot dead.

Fighting began late one November night, and early the next morning gang leader “Ti Lapli” led members of Gran Ravin in routing police and capturing the Carrefour-Feuilles sub-police station in Savine Pistache. Gangs often loot captured police stations of guns and ammunition.

The shipping container turned police station was retaken by government forces, but the gang sporadically shoots downhill towards it. At least one gang member was killed in those clashes with police.

Some HNP live in Savane Pistache, and Gran Ravin was shooting at those police to take control of the entire neighborhood when I visited on Nov. 14. One policeman dressed in civilian clothing and a balaclava raced up the hill on a motorcycle, a Glock with an extended magazine in hand. He returned downhill to relative safety with a young boy a few minutes later.

An unlucky stray bullet killed one man during the clash. Lead punctured his torso, leaving him stooped over a staircase to bleed out. The blood poured from his mouth, ears and chest into a congealing puddle on that dirty concrete.

The crackling of gunfire was still audible further up the hill. We decided not to follow. I had body armor; my fixer did not.

Residents fled down the hill for sanctuary at the bottom of Carrefour Feuilles, closer to the city center. People who abandoned their Savane Pistache homes now live in public high schools like Lycée National. About 320 people, including 85 children, sheltered there. Others fled to stay with family in safer parts of Port-au-Prince.

Later on Nov. 14, currently unknown gunmen fired at a US Embassy convoy. The state department reported no casualties, but recommends US citizens not travel to Haiti – citing concerns of kidnapping, gang violence and civil unrest. It was a lovely time for me as an American correspondent in-country.

Much of Savane Pistache is now abandoned. Empty homes are left for Gran Ravin. Neighboring parts of Savane Pistache are held by rival gang Ti Bwa. Both groups deal in kidnapping and extortion.

On Nov. 16, I was allowed to enter some gang-held areas in a different part of Savane Pistache, though my heavily-armed escorts wouldn’t disclose their group affiliation.

Masked men sat on the steps of abandoned homes, drinking and smoking. Most concealed their faces with tshirts, but others wore balaclavas or bandanas of various colors. Bandana color means nothing in Port-au-Prince. Gangsters in red bandanas fight with confederates in blue.

Some men had AR15 pistols. One had an Israeli Galil ACE – also a favorite with Haitian police. Some carried machetes. Gunshots were sporadic, though at a distance, and the odd 5.56 or 223 casing littered the road. I was not allowed to photograph the gang members, despite their obscured faces.

The gang members escorted me to their frontline – the part of Savane Pistache not held by any faction. Gang members peered from behind houses toward the opposition’s territory. We all ran quickly across the streets and took cover behind buildings. The odd shots rang in the distance, and I didn’t stay long. We were told to leave because some corrupt police were coming to do unspecified business with our gang tour guides.

These frontlines are across Port-au-Prince. Miserable people constantly plead to a compromised, overwhelmed police force to take action against Gran Ravin and other gangs. Refugees from other dangerous areas congregate throughout the city, and many in Haiti’s impoverished, gang-ridden slums believe they are forgotten by the current Henry government.

“Nou bezwen yon souf” — “We need a breath.”

Haiti’s compounding crises have had protesters in the streets for the past several years, but protests have only increased under the unpopular Henry – especially with his government requesting another international military intervention. Massive anti-government, anti-occupation protests happen regularly.

Protesters convened in downtown Port-au-Prince the morning of Nov. 18. I arrived in the morning when the crowd was still small. One protester waved a massive Russian flag, and multiple smaller Russian flags were present.

Some of the pro-Russia posturing comes from anti-American sentiment; the US embargoed Haiti for much of the 19th Century and US Marines occupied it in the early 20th. Then the US supported brutal, anti-communist Haitian dictators like François Duvalier.

Conversely, the Federation has raised concerns about another Haitian intervention at the UN Security Council.

Russian official Dmitry Polyanskiy said at the Security Council last October that “external interference in Haiti’s political processes, and subjugation of the country to the ambitions of certain regional actors (insinuating the US) who regard the American continent as their ‘courtyard’ is unacceptable.”

Other demonstrators carried the flag of the First Haitian Empire, a vertical bicolor of red and black. It was under revolutionary hero and Emperor Jean-Jacques Dessalines that, after victory over the French was secured, all the French remaining on the island were massacred.

The day’s protest began within an apropos Vodou ceremony. Folks congregated around an Oungan, or Vodou priest, as he drew a veve from a lightly colored powder onto the pavement of Rue Capois. A veve is a religious symbol used in West African Vodun and its diaspora religions. A veve serves as a beacon for the Loa, which is a spirit or saint in Vodou, while also representing that Loa.

Other Oungans and a Manbo, or priestess, placed and lit white candles on the edges of the veve while stacking wood scraps in the center. A police MRAP drove over the veve with impunity, angering worshipers.

One Oungan held an icon of Saint Expeditus – a Centurion martyred in Armenia and synchronized with the Loas Baron La Croix and Baron Lakwa. The Oungan kissed the icon before placing it in the pyre, while the old Oungan drank and spat rum libations around the veve. Rum dripped from his wispy beard. The pyre was lit. Practitioners orbited around the veve, chanting, as the flames rose from its center.

Hundreds piled onto Rue Capois during the ceremony. As the fire died and the ceremony closed, an impassioned crowd began their march through Port-au-Prince. Their lamenting was accompanied by drumbeats and blasting horns.

Police drove alongside to monitor the protest. Though they were armed with teargas launchers, M4s and Galils, most police watched with disinterest. Apathetic officers had headphones in their ears and listened to music instead of paying close attention to the protesters.

The tire fires began as we marched up John Brown Avenue. Frustrated youth, hidden under t-shirt balaclavas, ran into the streets with petrol and loose tires. Mounds of burning rubber permeated the streets. Police didn’t extinguish any, instead just driving around the flames.

It was scorching, miserably hot. I was dripping sweat and my camera was frequently overheating, but that was the least of my concerns.

My fixer and I had inexplicably separated. About four or five people singled me out for the obvious reasons. Fuming and screaming in my face they shouted unknown threats in kreyol, which I don’t speak. At least “Fuck you!” was in English.

One in the mob hand-gestured a knife slitting across his throat while he made the universal “schlick” noise. I heard a yell of Ameriken while someone else grabbed the back of my plate carrier. Immediately I broke into my limited Spanish.

“!No soy de los Estados Unidos! ¡Soy salvadoreño! !Soy de Ilobasco!” I shouted in my defense, with Ilobasco being the Salvadoran city where my partner’s family lives.

I pointed to the liberty pole tattooed on my right arm, pulled from the Salvadoran flag and coat of arms. I got that tattoo in Ilobasco, so my lie had some truth to it. One in the crowd did recognize that the tattoo was indeed from the Salvadoran flag.

Despite my atrocious accent, the ruse worked and they left me alone. I was free to continue my work.

The march ended at one of the multiple UN offices still in the city. One shipping truck, which accompanied the demonstrators, parked opposite the office building and multiple HNP Toyotas. Six or seven men climbed on top of the shipping truck, giving impassioned speeches.

One militant activist, clad in an ironic American OCP camo pattern while holding a Russian flag, condemned the government and the dismal situation in the country:

“They are selling their soul for [a] visa, and your kids are in the United States! Look what happened in Savane Pistache! Look what happened in Carrefour Feuille! Look what happened [to Haitian immigrants] in the Dominican Republic!”

“The Embassy of Canada and the Embassy of the US. We let you know the Haitian Nation is cutting its friendship with you. Madam Lalilem. She is the one federing (sic) the gangs and Michelle Natelly makes the gangs legal.”

The gangs, contrary to what the protester said, are not legal. However, prominent gang members are seldom prosecuted. For the most part, only low-level gangsters face any imprisonment.

“Today the Haitian people have to take their destiny in their hands. Today people have to save people. Today we have to help each other! Thank you for the people who are fighting with us.”

The protest ended shortly after without any further incident.

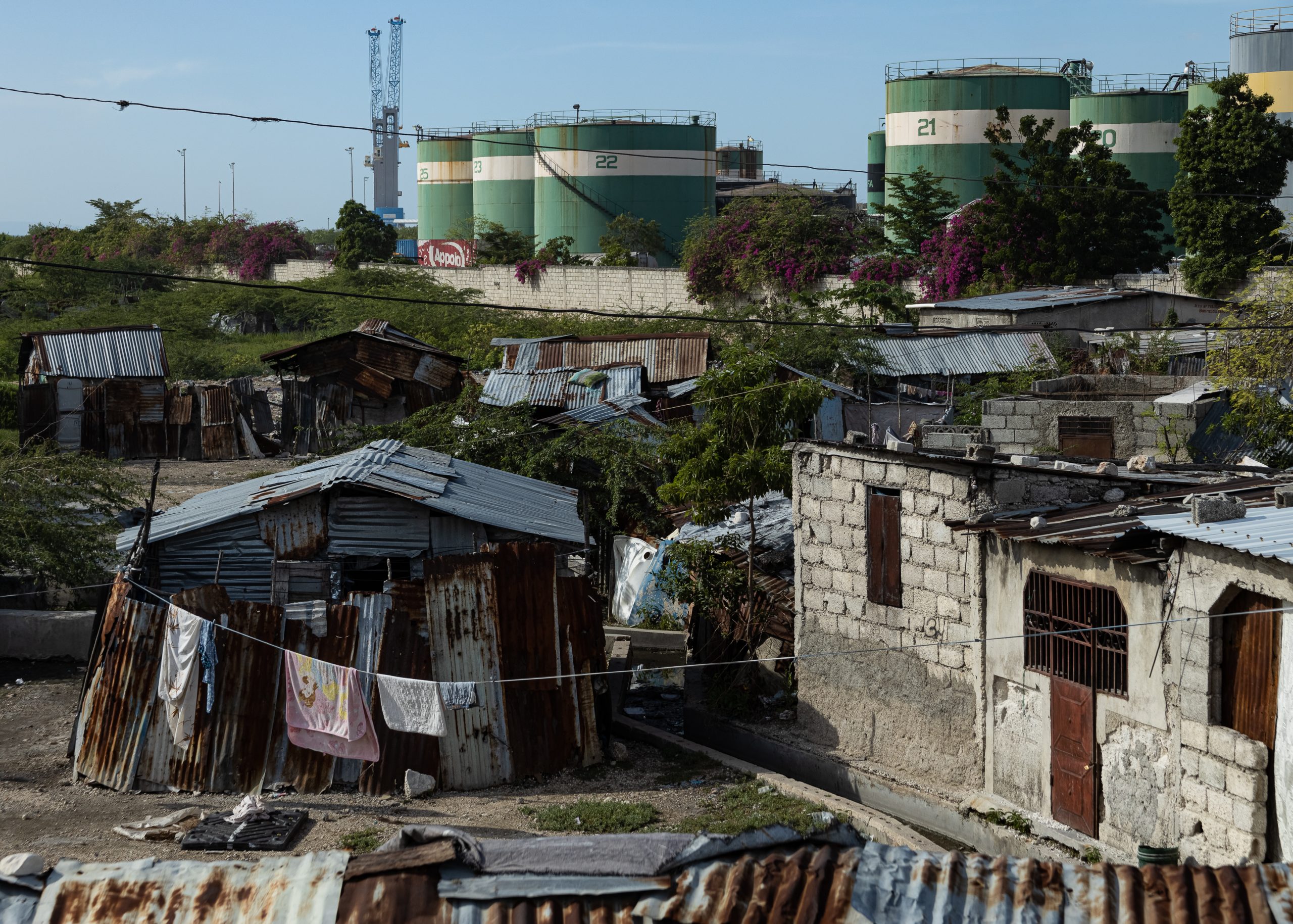

The Slum Cité Soleil

One of the worst areas in Port-au-Prince is Cité Soleil, bordering the international airport. The slum houses between 200,000 and 400,000 people in extreme poverty. It’s among the hemisphere’s biggest, most dangerous slums. People live in sheet metal shacks. The more fortunate reside in homes built from concrete blocks. Sewage flows through the slum in barely maintained, open canals – especially in the waterlogged ‘Brooklyn’ area. Unemployment persists, and many residents are illiterate.

Cité Soleil residents die more frequently than those outside the slum; they contend with brutal gang violence, starvation, endemic rape, complications from AIDS and a cholera resurgence. Two factions vie for control of the neighborhood: the aforementioned G9 and its dissenting breakaway G-Pèp. Allegedly, G-Pèp is tied to the Tèt Kale Party’s (PHTK) opposition. The bulk of fighting in Port-au-Prince is between these two gangs.

Different gangs have been in Cité Soleil for decades. Territorial lines shift as power has ebbed and flowed between upwards of 30 armed factions. The gangs forced police out of the neighborhood in the mid-90s and kept aid workers from entering the area. Violence increased through the early 2000s. Shacks were torched, and warring factions killed civilians.

United Nations troops, mostly Brazilian, tried to wrangle control of Cité Soleil from the gangs after 2004’s intervention. Government control of the slum was established in 2007, and the UN manned a checkpoint at the entrance. After the UN withdrawal, gangs quickly regained control.

Significant fighting broke out in 2022 when G9 men entered G-Pèp territory to depose leader “Ti Gabriel.” From July 8-9, a battle between the two rivals killed 89 people. 47 were gang members and 42 were civilians. At least 74 others were injured in the fighting. Fighting blocked all the roads in the Brooklyn neighborhood, trapping residents with gunfire.

In the five days between July 8 and 12, at least 234 people were killed in Cité Soleil. During that period, at least 50 women were gang raped – many in front of their children.

Police, who lacked both paychecks for the previous month and gas for their vehicles, failed to respond despite being nearby. Or, as activists say, used those excuses to not respond.

Nevertheless, a nominally concerned UN enacted a small arms embargo against “non-state actors.” Resolution 2653 also includes asset freezes and travel bans to be used “as necessary” against offending individuals.

Ultimately, the embargo makes little difference. Gang-owned small arms are purchased on the US civilian market before being smuggled into Haiti, or they come from the Haitian National Police – either stolen from the HNP or purchased from corrupt members. The HNP is obviously not a “non-state actor,” so countries can still supply the police force with weapons.

Evicting the Refugees

Before even entering Cité Soleil, I met refugees who fled the infamous slum and neighboring Tabarre. Violence erupts without warning, and bullets tear through flimsy tin walls. Some 3000 people fled from the neighborhood-turned-warzone.

At first, the displaced families found refuge in Plaza Hugo Chávez. The park, complete with a statue of the beret’d man himself, was provided by Venezuela in the PetroCaribe era. Some slept there for weeks, others months. However, as my fixer and I approached on Nov. 17, police were forcing the refugees out of their de facto camp.

The homeless screamed in despair, and many shoved a little piece of paper into my camera. The authorities, in lue of providing a place to stay, gave the people a paper slip that indicates how they once lived in Cité Soleil. It was a slip that helped the government take note of how many were displaced. Little more.

Other people received World Food Program coupons that listed food distribution times.

“We can’t eat! We are sick and have no water! We have cholera! The gangs took over [our] house and destroyed it. We need help!” one woman with a broken voice screamed.

Another older woman held up a photograph of her son’s corpse and indicated to me where he’d been shot. Bullets peppered his torso, and tore through the young man’s jaw and face.

Police were an impediment to reporting. When we first approached, masked cops told us we couldn’t go further. One grabbed my fixer by the back of the shirt and yanked him back. Then they argued in kreyol. Police made empty threats about detaining us before we left and approached Plaza Hugo Chávez from a different angle.

Government-commissioned workers were rapidly constructing a fence around the park to keep more refugees from entering while police were working to evict those inside. We found a choke point where people were being forced out and worked our way against the crowd. Once inside, we were again met with police. This time they were much more hospitable. They barred us from going further into the park, forbade us photographing them, and politely made us leave. We hopped over a 2×4 board that was tacked up at the choke point to dissuade more people from entering, and then we left the park.

The next morning, the police used teargas to evict the families that remained in Plaza Hugo Chávez. We met those who were gassed, sleeping on the streetside in Delmas by a mural of a woman in a covid mask. About 100 people were there.

Cracked voices shouted their pleas. “This is abuse!” a woman repeatedly bellowed. Again, the displaced angrily waived those damned slips of paper. One refugee named Diveanal spoke English and was eager to explain their plight.

The assistance promised was hardly anything. Some were ‘lucky’ enough to have received 2000 Haitian Gourdes – about $14 US. Others received much less, if anything at all.

“Some people that were fortunate to get the money only found $200 Haitian dollars. Some found $400 Haitian, some found $300 – which is not enough to find us a place to stay or afford us a place to stay,” Diveanal explained.

The police fired teargas into the families that refused to leave the park, having nowhere else to go. Diveanal said it well: “The police came and offered us teargas as compensation for our pain.”

Frantic parents tried putting toothpaste in the nostrils of their children in a feeble attempt to protect them from the gas. Some adults tried using toothpaste on themselves. It made no difference, and two infants died from inhaling the gas that morning.

It seemed silly to me with my respirator to use toothpaste to try stopping teargas, but I’m not a parent trying to save my child. Desperate people will try anything to survive, and tear gas will kill children.

Diveanal introduced me to a woman whose infant daughter survived the gas. The woman changed her weeping baby, and there was residue from toothpaste still in her eyebrows. Most was wiped off, but it showed an attempt by the mother to keep teargas from her baby’s eyes. Her little eyes were still red.

“This baby right here was one of the babies that were there during the time that the teargas was going out. Unfortunately there were two other babies that lost their life this morning because of the teargas,” explained Diveanal.

Seated behind her, another woman wept as she clutched her young son drinking juice. Surrounding women cried over the morning’s events.

“You know, the baby mother was fortunate enough to take the baby and run with her before anything worse happened. But unfortunately we lost two babies this morning.”

Homeless, Cité Soleil’s former residents have nowhere to go. They can’t afford new homes or much food. Some of those forlorn people swarmed around an aid van that drove by with supplies.

Before I left, Diveanal had some final remarks:

“We have been out of Cité Soleil for the past 4 months of war. We can not support this anymore. This is unfair. This is unfair. This is my country. I’m not supposed to be suffering like this.”

Avèk Gang la

Immediately after meeting the displaced, I entered Cité Soleil and the surrounding slums for the first time, but only after passing by the filth of Solidarite Market on Boulevard La Saline. The produce market reeked of discarded, rotting goods piled on the opposite side of the road. Rancid sludge turned the dirt road to a putrid mud. A goat picked at the street side garbage pile.

We had permission to enter the gang-controlled neighborhood, and an escort took us in deep. I know what gang my heavily-armed guides were in, but they and my fixer requested it not be disclosed. Much of La Saline and Cité Soleil were visible from our locale, as was the recently blockaded Verreaux fuel terminal by the coast.

Our escort wore a red bandana over his face, but refused to be photographed. I pointed out that his AR pistol was missing its forward assist – a small button behind and above the trigger that pushes the bolt forward in the event that a round doesn’t seat in the barrel properly.

The forward assist is a mostly unnecessary feature, but there was a gaping hole where it should have been. While surprised I’d noticed, he declined to explain why it was missing. He did, however, exhibit good trigger discipline, much to my relief and surprise.

Per the World Food Program, some 19,000 impoverished tenants face starvation in the slum. The gangster took us to see the most visible indication of this food insecurity – mud cookies. To stave off hunger, starving Haitians eat air-dried, not cooked, disks of strained chalk, vegetable oil and salt. They cost only a few cents, and taste as bad as expected. I could only manage a few bites of mine, and felt ill after. Dirt isn’t particularly nutritious.

We returned to the slum the next day. This time, the gang members allowed photographs. I just needed to tell them first, so they could remove their shirts and wrap balaclavas. Without shirts their ribs were on full display. The slum’s streets were sometimes flooded with filthy, excrement ridden water. It was here, in trash-filled water I clumsily stumbled through, that the cholera resurgence was discovered.

Four gang members took us to one of their frontlines, and we met a few more men on the way. Their territory stopped at a concrete wall that ended at a waterway. Trash washed downstream and piled against the wall. One militant stood atop the mound of trash, and he positioned his AR15 through a gap between two cinder blocks. The man aimed his rifle at the enemy’s territory, positioned to fire at members of the opposing gang. He didn’t fire this time.

No one peaked too far around the concrete wall for that reason. The enemy gang had snipers too, and there were several choke points in Cité Soleil where we kept our heads low to avoid being a target.

The Murder of the Activists

The funeral was at Notre Dame d’Altagrace, a modest Catholic church on Route de Delmas. That road is a kidnapping hotspot. This was no ordinary funeral, no civilians killed by stray bullets. These five men were targeted specifically because of their activism. And now, they have become martyrs.

The five slain were Enock Merisier, Dieupuissant Orestil, James Mondesir, Paul Ezekial and Andy Moriseau. They were found murdered a few weeks earlier on Oct. 31, 2022. Their bodies were dumped near the US Embassy in Tabarre 43. Allegedly, they were killed by police – or at least men pretending to be police.

The deceased were activists from a group called Baz 47, which campaigns for the Platfòm Pitit Desalin political party. Platfòm Pitit Desalin promotes Haitian nationalism, leftwing populism and social democracy. The party opposes the Henry Administration, leading to accusations that the Henry government was behind their supporters’ deaths.

Paul Ezekial, one of the victims, started the Bwa Kale protest actions in response to the Henry government’s decision to remove fuel subsidies.

Jean-Charles Moïse, Secretary General of Platfòm Pitit Desalin, quickly condemned the arrest on Twitter before it was known that the five were dead. “We denounce this illegal act and demand their release. We hold Ariel [Henry] responsible for the criminal acts committed in the country,” he wrote.

Per the Gazette Haiti, the HNP has not clarified if it was real or fake police that apprehended the Baz 47 members. However, it’s widely accepted that gang members sometimes disguise themselves as police.

Earlier in September, 2022, three other members of Baz 47 went missing. The three were riding a motorcycle to meet the leader Sekté Popilè, another group, when they were allegedly intercepted in Croix-des-Bouquets by members of 400 Mawozo.

In a courtyard outside the church Jeune Presmy, a delegate from Baz 47, held an impromptu press conference. Baz 47, he said, is an activist group that fights to improve conditions for the Haitian people. “Our battle is for a better life for each Haitian person and for security and [for] everybody [to] get something to eat, he said.”

Presmy explained what happened to his friends the night they were abducted. He looked into my camera specifically, imploring the international community to pay attention to the plight of Haitians.

According to Presmy, he and other Baz 47 members were getting together to “talk about politics” when a police car approached. A second police car was short behind. Presmy then got suspicious and fled.

“When I saw the second car, I then thought this might not be real police and I left,” he explained.

From a hiding spot, Presmy claims he heard the ‘police’ point their guns at the remaining Baz 47. The officers shouted “Get in the car! Get in the car!” and apprehended five of the men. Two others escaped.

Thinking their friends would be taken into custody, Presmy and a few others tried calling the police to see where the five were being held. Calling showed no results, so they went to the nearby police station to inquire. The police had no record of the five being detained.

The police meanwhile had no clue about the five abducted. Then, they received a phone call saying five men were killed and their bodies were found near the US Embassy. Baz 47 sent someone to the morgue, and he identified the bodies as the missing members.

Presmy made explicitly clear that Baz 47 is no gang, but instead a political party. “We are not a base of people who are holding guns in our hands,” he said. “We never kidnap people. We are not going to force people to give us money.”

Lamenting over his slain comrades, Presmy said this:

“Today it’s the criminal Government, instead of helping us they [are] choosing to destroy us instead. They are trying to destroy the young people who have a dream. Those guys who have a dream, they asked for a better system. But they are taking us and killing them instead.

They label us as a robber so they can kill us. We are young , we [have] been together for 10 years doing politics. Nobody before [has] said anything bad about us before. Since then, the intel police have never found anything guilty on us, but the Government [is] sending fake police to take us and kill us.

We don’t deserve this because we want a change for Haiti. Ariel, we don’t deserve this. Baz 47 doesn’t deserve this. We are not a gang. Please the international [community] think about us.”

People congregated outside the church prior to the service beginning – loved ones and supporters alike. Mourners wore everything from t-shirts to three piece suits. Some smoked cheap cigarettes. Others drank.

A few mourners smoked seedy cannabis wrapped in sweet tobacco leaves that I came to know well over my two weeks in Port-au-Prince. Cannabis mixed with tobacco is a common scent in parts of downtown. The herb was always dry and crumbling, filled with seeds and stems that no local ever wanted to throw out when rolling up. But the flavorful wrap more than made up for the mediocre quality. It was a full bodied, delicious smoke. A leaf-rolled blunt is the preferred method for Port-au-Prince stoners. I never saw any papers.

One demonstrator outside the church wore a sign: “USA and Canada FUCK YOU!!! Stop your killing against Militants and Journalists.” In Haiti, the words ‘activist’ and ‘militant’ seem used almost interchangeably. Anyone can be a protester, but only dedicated activists are called militants.

Again, some Haitian outside Notre Dame d’Altagrace was mad at me specifically. He shouted profanity over me being a US citizen. My government, he felt, was responsible for much of his country’s calamities. He perceived my taxes, vote and complacency as a cause for his suffering.

Even though he spoke very little English, we ultimately reconciled through an intermediary before he and others shared a blunt on Route de Delmas. Again, the quality was abysmal, but I’m told it smoked nicely.

Soon the memorial service began, and it seemed more a chaotic skit than a funeral. About a third of those in attendance were streamers – local media that live streams events with their cell phones mounted in stabilizers. They were the most annoying group, always blocking my camera.

The rest in attendance were community members, friends or activists themselves. A few mourners were familiar faces I recognized from the protest a few days prior – including some of the Oungans that blessed the demonstration.

Grieving loved ones cried or shouted profusely as if in physical pain. The mothers of the slain wailed. Streamers crowded around crying family members – eager to broadcast the tears to their roughly 30 viewers. The living activists shouted their rhetoric at the cameras present. The chaos and shouting made the priest performing the funeral rites barely audible, despite his microphone.

Mourners started pouring out of the church and onto Route de Delmas immediately at the wake’s end, meeting other activists already assembled in the street. The crowd marched north from the church to the banging of drums and chants decrying the Henry government and the dead activists. No tire fires this time.

“Those guys were trying to tell Ariel [Henry] that he represents the system and if we want to go against the system we have to fight him first,” a friend of the deceased and member of Baz 47 told me after the service.

“We ask for the minimum, but instead of helping us out, they are making us cry. [Henry is] choosing to disappear us and take us to the jail,” the man said.

“They are choosing to assassinate us. Then we have Baz 47. As activists this is a normal battle. This is a battle for the next generation. This is a battle for the people who suffer in the ghetto. This is a battle for people who can’t afford food and children who can’t go to school. The battle is for the police also, who are doing oppression on the people. We are a good gang.”

Uncertainty Remains

Since I left Port-au-Prince, the situation has deteriorated further. On November 25, 2022, the day after I left Haiti, the head of the Haitian National Police Academy was assassinated by unknown gunmen. Academy director Harington Rigaud was gunned down while inside a police vehicle by a police training center in Port-au-Prince.

Shootings remain a daily occurance, and several dozens of civilians have been killed in gang clashes over the passed few months. Haitians continue being kidnapped.

Most recently, six police were killed after the gang Gan Grif attacked a police station in Liancourt on January 25, 2023. They were stripped naked and their mangled bodies were shown in a widely shared video. The gang members sadistically propped their guns against the naked, dead police, like hunters with their quarry.

Per the HNP, Gan Grif still has their corpses

Police responded with protest yesterday in Port-au-Prince – guns in hand. Members of the police gang Fantom 509 and their supporters lit tire fires in the streets, shot guns in the air and blocked roads with commandeered buses. Rioting cops smashed car windows. Some of the rogue police stormed the international airport. More brazen ones attacked Prime Minister Henry’s home, breaking through the outer gates. The Prime Minister was unharmed.

Fantom 509 demands better conditions for police, that the government put down the gangs and that Prime Minister Henry resigns. At least 78 police have been killed since Henry assumed power.

Foreign intervention seems a real possibility. The Haitian government continually stresses that an anti-gang task force is needed. Last December, the Canadian UN ambassador visited Haiti to discuss a potential intervention with members of the Haitian Government.

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres suggested a “rapid action force” of Special Forces personnel to suppress the gangs late 2022. Although any foreign intervention likely wouldn’t be a UN mission, it would have UN backing.

Most likely, a potential international force wouldn’t target gang strongholds, but rather control critical infrastructure in Port-au-Prince. By occupying the ports, airport and key roads, the multinational force would create safe corridors of travel for people and goods. This would allow locals, self quarantining to avoid kidnappers and gang fighting, to seek often neglected medical help, go work or go to school. The control would provide the abysmal economy with much needed support.

Earlier this January, President Biden and Canadian Prime Minister Trudeau discussed sending a multinational force to Haiti to quell the violence. At a bilateral meeting in Mexico City, the leaders mulled over a possible multinational police contingent that would assist the Haitian National Police. But neither the United States or Canada is eager to head such a police force. Brazil also refused to lead the force, after being the main military component of the last UN intervention.

So far, despite international consensus that Haiti needs an intervention, no country seems willing to lead one. The last intervention failed and the Haitian people suffered under impune occupiers. Besides, any foreign action would be seen by many Haitians as backing the unelected, unpopular Ariel Henry. For now at least, crises will continue to compound, and the Haitian people will continue to suffer.