The Colombian Conflict is an ongoing 60-year-long multifaceted war between government forces, leftist guerillas, and right-wing paramilitaries. The conflict has taken an estimated 450,000 lives while hundreds of thousands of others have been declared missing amid the fighting between belligerent forces. The conflict itself has gone through numerous changes, from active military engagements to long-term ceasefires with some groups ultimately disarming and disbanding following successful peace deals with the government, although recidivism is rampant in Colombia’s deals with militant groups with cycles of peace and rearming. Peace for Colombia is a goal of current President Gustavo Petro, who established a controversial plan to bring “total peace” to the nation the president seeks to end the internal armed conflict through a series of ceasefires with the hope of a long-term solution.

The Start of the Conflict

The origins of the Colombian Conflict lie in the rise of left-wing political activist and presidential candidate Jorge Eliecer Gaitan. Gaitan was a key figure within Colombia’s Liberal Party, championing workers’ rights and the inclusion of minorities in Colombian society and campaigning against the nation’s ruling landowning elite, which held significant sway in the nation’s politics.

Gaitan was assassinated in 1948, sparking a massive riot in Colombia’s capital of Bogota which quickly spread to other cities within the country. The riot in Bogota, referred to as the Bogotazo, culminated in the lynching of Gaitan’s killer and rioters converging on the Presidential Palace with the alleged goal to kill acting Conservative president, Ospina Perez, who many believed to have orchestrated the killing of Gaitan.

Once the riot was quelled, a period of violence engulfed Colombia. This period, aptly named “La Violencia” saw leftist guerillas and right-wing paramilitaries enter into a fierce war with the government alongside each other. Leftist guerillas began ambushing government forces while right-wing paramilitary groups, with the complicity of public officials, seized the land of those who they deemed communist supporters. These attacks would lead to the deaths of hundreds of thousands, and displace millions of peasants from the countryside who would flee to the urban cities of Colombia. Their relocation would lead to the formation of communist popular brigades in the cities, and would help form future guerilla groups such as the National Liberation Army (ELN).

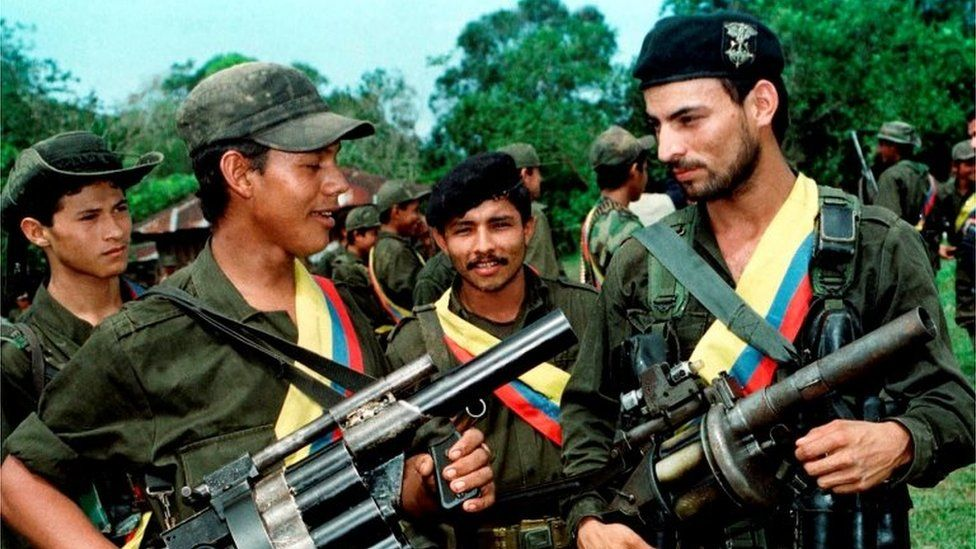

From the conflict, a number of armed groups were formed. These groups included the aforementioned leftist guerilla group, the ELN, alongside one of Colombia’s most prolific groups which is active to this day, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). The group’s origins trace back to an attack in 1964, where 48 armed FARC defenders stood against 16,000 Colombian troops. Despite being outnumbered and outgunned, the survivors regrouped and retreated to safety in nearby mountains where the early form of the FARC took shape. The FARC quickly expanded operations, at first only attacking government convoys in small-scale guerilla attacks before they found their primary source of income, cocaine.

This new source of income was the result of the “Coca Boom,” a period in which the production of coca, the key ingredient to the production of cocaine, would increase exponentially, expanding the groups’ coffers with more funds for operations. This allowed the FARC to bring in more guerillas, offer proper training, and obtain better weapons for their war against the government. With the increased funding, the FARC would transform into a true rebel power, and at a FARC leadership meeting now known as the “Seventh Guerrilla Conference” in 1982, the group would expand their operations to urban areas of Colombia, while sending promising soldiers to the Soviet Union and Vietnam for professional training.

Alongside cocaine, the FARC also began a series of kidnappings, holding those they stole from their homes for ransom. The group would also extort locals and businesses, collecting “taxes” in order to fund their efforts against the government and their right-wing rivals, the United Self Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC).

The group continued operations until a windfall peace deal with the government in 2016 under the presidency of Juan Manuel Santos that saw the bulk of the FARC disarm and return to regular civilian life. Despite the ceasefire, however, several remaining hardline members of the FARC and those who did not wish to forfeit their exclusive and profitable careers continued their operations against the government and the people of Colombia. These groups would label themselves as “fronts,” a leftover from the group’s original structure, and break into two factions.

Among those who rejected the ceasefire was the Estado Mayor Central faction of the FARC (FARC-EMC), formed by one of Colombia’s most wanted criminals, Miguel Botache Santillana, going by an alias Gentil Duarte, who was a main negotiator during the peace conference between the FARC and the Colombian government held in Cuba. After negotiations failed, Duarte returned to Colombia and attempted to unite FARC’s other fronts into one body and continue the organization’s armed struggle against the government. This would succeed, and in 2017, Duarte and another commander, Ivan Mordisco, would announce the birth of the united FARC-EMC.

Their main rival would prove to be the Second Marquetalia, which was formed by several former FARC commanders, many of whom previously accepted the ceasefire but would rearm in 2019. The group’s main territory encompasses the Venezuelan-Colombian border, where the FARC has historically enjoyed a great deal of protection from authorities in Venezuela. The Second Marquetalia would even come into conflict with another dissident faction of the FARC. This faction, known as the 10th Front, had refused to support the leaders of the Second Marquetalia, who had attempted to pull rank on the dissidents in Venezuela following their rearmament. Following the refusal, the 10th Front would face direct action by Venezuela’s military, in what Insight Crime reports was an attempt to grant further power to the Second Marquetalia.

It was these operations conducted by the early FARC that led to the formation of the AUC, another group that has persisted through their own agreed-upon peace agreement and subsequent disbandment. The AUC draws its origins back to some of the first paramilitary groups in Colombia, most notably the Peasant Self-Defense Forces of Córdoba and Uraba (ACCU). The ACCU was founded in Córdoba by three brothers, Fidel Castano, Carlos Castano, and Vicente Castano, after their father, a wealthy landowner and right-wing supporter, was kidnapped and killed by the FARC.

The group would adopt a number of similar methods in order to raise funds as the FARC, extorting locals and producing cocaine to be sold in the United States and other nations. The AUC officially continued operations until 2003, when the government offered a peace deal to the group. The deal originally allowed disarmed members to keep their illegally-procured assets and avoid prison, serving what little time they were sentenced to on lucrative private farms. Those terms continued through 2006, when the Colombian government refined the terms of the peace deal to appease widespread demands that punitive action be taken against those wishing to disarm for their previous crimes and activity.

However, a large number of members refused to lay down their arms and accept the terms, leading to the AUC’s collapse into dozens of splinter groups. The most noteworthy offshoot was Clan del Golfo, a narco-terrorist organization active in the AUC’s old territory in northern Colombia. This newly born group would be led by Vincente Castano, and under his leadership, the group would continue many of the AUC’s methods to raise funds, including extortion, kidnapping for ransom, and, most importantly, producing and trafficking cocaine.

Clan del Golfo would go on to dominate the cocaine trade after conquering rival criminal and splinter groups from the dissolution of the AUC, quickly becoming one of Colombia’s most notorious criminal groups with the government dedicating large-scale military operations in an effort to bring them down.

The National Liberation Army (ELN) was founded in 1964 by a group of Colombian communist rebels who were formally trained in Cuba. The group would later be led by Catholic priests who practiced Liberation Theology, a belief system focused on addressing wealth inequality within Catholic teaching and through the clergy. A number of similar theological methods would also be adopted by Catholic priests in nations spanning from the United States to South Africa and even South Korea.

The ELN also historically operated in Venezuela for decades; these operations only increased following the disarmament and disbanding of the FARC in 2016. Following the FARC’s disbandment, the ELN and Clan del Golfo quickly began to occupy the newly vacant territory, leading to a number of clashes between these groups and government forces.

A Peaceful End?

The current administration under President Petro seeks to end the violence that has plagued Colombia for over half a century through peaceful means rather than violent confrontations with armed groups. This strategy to end the violence was first suggested with the passage of Petro’s Total Peace law, a law that allows the president to initiate peace talks with Colombia’s rebels. The law’s passage has cemented the government’s efforts to end the conflict through negotiation and peaceful means as state policy rather than that of Petro’s administration. This means that peace agreements with armed groups cannot be overridden by following governments, which allows for more secure negotiations with participating groups.

The law not only allows the president to arrange peace talks with armed fighters, but also seeks to place the community first amid the talks. Among these efforts for community-centric solutions was the creation of the peace fund which invests in infrastructure, education, and healthcare in areas heavily affected by the conflict.

Petro also seeks to stem the conflict by attacking the smuggling routes of cocaine to foreign nations, stating that the fight against drug trafficking is “not where coca leaves are grown … It’s where cocaine becomes Colombian money.”

Among those included in Petro’s “total peace” plan are the ELN, Clan del Golfo, another right-wing paramilitary known as the Self-Defense Forces of the Sierra Nevada of Santa Marta, the FARC-EMC, and Second Marquetalia.

However, Petro’s plan has hit a number of roadblocks throughout his presidency. First, the ELN suspended peace talks with the Colombian government following the government’s decision to enter talks with the ELN’s Narino front outside of the national representatives for the armed group, a move the national leadership ultimately rejected.

The ELN claims the act was, in reality, part of the government’s plan to target the group’s command structure in one of the group’s publications, Insurreccion 947. The group claims that the peace talks with the Narino front have only matured due to the supposed government agent’s failure to target the core leadership of the ELN.

Furthermore, the publication states that this issue was brought up by the organization’s official negotiators at meetings with the Colombian government but was ultimately ignored, resulting in the ELN leaving the talks.

“Now, activating the supposed ‘dissidence,’ the government has given priority to said setup, relegating the official Roundtable with the ELN and therefore confirming that its priority is to hold peace dialogue with its own intelligence agents,” the publication stated.

In another blow to Petro’s total peace plan, the government was forced to suspend the ceasefire with the FARC-EMC following the group’s attack on an indigenous community that led to the death of a community leader and the injury of two members.

The community leader, Carmelina Yule Pavi, was killed after attempting to help two minors who were being kidnapped by the FARC, likely to serve as forced conscripts in the organization’s war against the government.

Attacks against this community did not stop, however, as the caravan that was transporting Yule’s body was also attacked by the FARC-EMC.

Following the broken truce, the Colombian military would engage in operations against the FARC-EMC, leading to an increase in engagements with the criminal structure and government forces.

These engagements are likely an effort to force the Colombian government to restart the ceasefire with the FARC-EMC, a desire largely attributed to the group’s increase in manpower, narcotics production and distribution, and territorial gains.

“No matter how much pressure these illegal organizations try to exert, we will not back down from the decision to suspend the ceasefire. Offensive operations by the Public Force [military and national police] will continue,” Defense Minister Ivan Velasquez stated in April, seemingly confirming this theory.

“This organization has only filled the communities in these departments with anguish and suffering, and it is precisely because of these criminal actions against the population that the government, the President of the Republic, decreed the suspension of the cessation. And no matter how much pressure is intended to be exerted, we are not going to decline this decision taken to suspend the cessation and develop offensive operations by the Public Force,” Velasquez continued.

Meanwhile, talks have not been established with Clan del Golfo due to the group’s classification as a criminal group rather than an insurgency like the FARC and ELN. This inability to establish peace talks is in spite of Clan del Golfo’s reported willingness to enter talks with the government in March. Despite this hurdle, the Colombian Supreme Court altered President Petro’s Total Peace law in 2023, allowing the government to negotiate with criminal groups but disallowing offering disarmament, which would allow members to return to Colombian society. If Clan del Golfo wished to negotiate disarmament, they would have to do so through the Prosecutor’s Office, weakening the power the President would normally have in negotiations.

There remains some hope, however, as the Colombian government began peace talks with the Second Marquetalia on Monday.

The peace talks are taking place in Venezuela’s capital of Caracas, a historic location for talks between the Colombian government and various armed groups within Colombia such as the FARC and fellow leftist guerilla group, the National Liberation Army (ELN). Talks are expected to last until Sunday, June 29.

Armando Novoa, who is leading Colombia’s peace delegation, told Reuters that the government hopes to arrange a long-term peace deal before Petro leaves office in 2026. Novoa further stated that he hopes the peace talks progress quickly as many of those representing the Second Marquetalia participated in the 2016 peace deal which saw the majority of the FARC disarm and disband under president Juan Manuel Santos.

These peace talks are reportedly not intended to achieve a full disarmament of the Second Marquetalia, but to achieve a “de-escalation of violence in the territories where they [Second Marquetalia] operate,” according to Otty Patino, Colombia’s High Commissioner for Peace.

The leader of the Second Marquetalia, Luciano Marin, better known as Ivan Marquez, confirmed the Second Marquetalia shares the same motives. “Today we want to state that the Second Marquetalia of the Bolivarian Army, under my command and its collective leadership, is fully prepared to contribute to the common achievement of peace for Colombia,” Marquez stated at the event.

Petro’s “total peace” plan has faced severe criticism, with many opponents of the president’s strategy claiming that illegal operations targeting Colombian citizens have continued amid ceasefires with the FARC-EMC and ELN. Those against the plan took to the streets of cities across Colombia in April to voice their displeasure, with protestors in Bogota converging in Bolivar Square, where Colombia’s Congressional buildings and Presidential Palace are located.

“This is a call we are making to President Gustavo Petro and the ministers of this government. Let’s change the policies and open the doors to people who truly work for Colombia.” Henry Cárdenas, president of Fedetranscarga told the press during the protest. “Let’s seek benefits for the drivers who, every day, work for our country. They carry the economy on their backs. Yes to them, but let’s not seek more benefits for the vandals on the streets, let’s not seek more benefits for the groups outside the law.”

The protests themselves have been peaceful, with protestors in Bogota cheering when the Mobile Anti-Disturbance Squadron (ESMAD) which specializes in observing protests and dispersing those that turn violent arrived to oversee the protest.

Protestors reportedly united from a plethora of different political parties, with a number of leaders stating that the protest is not for certain individuals or party politics but to express the dissatisfaction that protestors have with Petro.

“Colombians, the day has come to defend democracy. It’s now or never,” Jaime Arizabaleta, a journalist and activist, stated. “We do not come out for any political party or any specific leader. Everyone fits in this march; this march has no owner.”

“The Government has failed to fulfill all its promises, security is at rock bottom, vandalism took over the cities, the guerrillas returned to the rural area and the country is in free fall,” veterans of the Colombian military told Semana during the protests.

A Crackdown

Since the Colombian government suspended the ceasefire with the FARC-EMC, the military has revived offensive operations against the group. As a ceasefire has yet to be negotiated with other factions within Colombia, they too are engaged in armed conflict with the government forces.

The efficiency of direct conflict with armed groups remains questionable at best. While offensive operations have prevented groups such as the FARC-EMC from solidifying power, with their increase in operational ability largely attributed to the ceasefire negotiated under Petro, prior direct operations have yielded less than desirable results. Prior to the 2016 peace deal under President Santos and Petro’s ascension to the presidential office, the Colombian government pursued militaristic measures against armed groups active within the country.

Notably, President Alvaro Uribe who held office from 2002 to 2010 launched a number of offensives against the FARC during his presidency. Four policies enacted by Uribe stand out amid the backdrop of the conflict.

Uribe’s first move to fight against armed groups active in Colombia was the Democratic Security Policy, a plan to counter armed group’s influence in the country through increased military pressure. The plan, which was revealed in 2003 and lasted until Uribe left office, sought to increase police presence across the country after authorities were effectively cut off from areas with a large presence of armed fighters, destroy narcotics production centers and coca plantations in order to counteract armed group’s main source of income, increasing defense spending, and increasing the capabilities of Colombia’s intelligence services.

Uribe’s Democratic Security Policy was largely a success, with Colombian authorities regaining control over rural reaches of the country, offering alternatives to farmers who relied on coca for a living, and increasing the size and efficiency of the Colombian military. However, critics of the policy argued that while Uribe’s plan increased the general security of Colombia, it ignored key issues within the conflict and sought to treat symptoms rather than the root causes that led to the formation of armed groups. Critics further pointed to a number of extrajudicial killings and human rights violations, such as Colombia’s “false positives” scandal, which continued throughout the president’s tenure.

Plan Colombia was another hallmark success for the president. Originally negotiated by Uribe’s predecessor, Andrés Pastrana, and US President Bill Clinton in 1999, Plan Colombia consisted of extensive foreign aid to Colombia in order to combat the country’s narcotics producers and increase security within Colombia. The plan consisted of extensive funding to Colombian authorities, with the United States investing approximately $10 billion to the Colombian government within the first ten years of the plan. Most of these funds found their way to the Colombian military and police force and are believed to have helped contribute to a massive reduction in the production of cocaine within Colombia, with a 72 percent drop in production from 2001 to 2012.

Critics of this plan raised similar concerns to that of Uribe’s Democratic Security Policy, alleging human rights abuses and extrajudicial killings while some in the United States argued that the country should not be funding a foreign nation, much less a nation which had been accused of mistreating its own civilian population.

Furthermore, the Colombian military launched a series of high-profile raids on FARC camps across Colombia amid Uribe’s US-funded Democratic Security Policy. One such operation was Operation Phoenix, a raid on a FARC camp in Ecuador in 2008. The raid was made possible through the wiretapping of satellite phones used by the FARC in their own operations by the DEA and FBI. On February 27, authorities intercepted a call between Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez and FARC commander Raúl Reyes, the second in command of the FARC, according to an unnamed source within the Colombian military. The call reportedly was about the release of a number of hostages held by the FARC on the same day, and following its interception, authorities traced the call to a camp near the Colombian-Ecuadorian border.

Colombia launched an attack, bombarding the location of the camp with ordinance before closing in with special forces units. Members of the FARC were quick to respond, returning fire to the approaching Colombian troops as they neared the encampment, killing one Colombian soldier in the process. After their loss, authorities opted to bombard the encampment a second time, killing at least 20 FARC members alongside Reyes. But the attack would not be received well by the Ecuadorian government.

According to Ecuadorian officials, the bombardment and subsequent storming of the encampment occurred within Ecuadorian territory without permission from the country and many of those killed were recovered in underwear and other sleeping clothes. Ecuador labeled the attack a massacre, with Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa claiming that bodies recovered by authorities showed signs of being shot in the back of the head. Despite the controversies, the operation was deemed a success. The death of Reyes marked the first time Colombian authorities killed a member of the group’s leadership council in combat and dealt a mighty blow to the organization’s structure.

But controversies remained, and Uribe’s aforementioned “false positives” scandal shook the country in 2008 after human rights organizations reported that young men from poor neighborhoods across Colombia were lured to their deaths by authorities.

During this scandal, the Colombian military offered a number of rewards for soldiers with a large kill count against the FARC. These incentives led to the deaths of an estimated 6,402 civilians who were lured to rural areas of the country, killed, and dressed in FARC uniforms before being passed off as guerillas.

After the scandal was discovered, the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP), a transitional court system that played a massive role in facilitating the peace deal between the FARC and the government in 2016, began an intensive investigation into multiple figures in the military, with more than 3,500 members of the military being placed under investigation.

During these investigations, officials have stated that many of the false positives were conducted in order to please ranking officers, with former commander of the Colombian army and retired general, Mario Montoya, being accused of at least 130 killings. Officials testified that Montoya ordered soldiers to prioritize kills over captures of rebels.

In the trial, prosecutors alleged that three generals, including Montoya, did not take sufficient action to prevent the false positives from occurring, while further claiming that some of the defendants had given orders directly to their subordinates to misidentify and murder civilians.

“From the command they occupied, they were permissive, lax in controls, and did not exercise their powers of prevention, investigation, and sanction. This facilitated the dissemination, permanence, and concealment of the crimes. Their omissions contributed to the consolidation of the three macro-criminal patterns documented in the Huila Subcase, one of the six areas prioritized in the investigation,” a document alleging the crimes stated.

Military units under the command of the generals are believed to have been responsible for a significant number of civilian executions, with 192 of the 264 deaths between 2005 and 2008 reported by the units being thought to have been civilians who were purposefully misidentified as guerillas.

In October, the Colombian government issued a formal apology for the killings. Minister of Defense Iván Velásquez issued the apology in Bogota’s main square alongside Colombia’s army head, Luis Ospina Gutierrez, and President Gustavo Petro.

Conflict Embedded in Colombia’s Future

Despite the relative success of Uribe’s policies in restoring order across Colombia, the conflict continued throughout both his and his successor’s presidency. This, alongside numerous controversies related to human rights abuses, has led some to oppose a militaristic strategy with those opposed fearing that their own lives may be at risk by authorities rather than armed insurgents. Others claim that a militant policy does not address the core causes of the conflict, again arguing that such a strategy would treat symptoms of the conflict rather than ending the conflict at its core.

Others in support of a return to military action argue that peace has only strengthened armed groups within Colombia and will not result in an end to Colombia’s bloody conflict in the future. Those supportive of direct action argue that only through a brutal show of force will Colombia’s armed groups be pacified and eventually forced into disarmament and disbandment.