In looking at the modern history of Rwanda, the small, landlocked nation nestled in-between Uganda to the north, Burundi to the south, Tanzania to the east, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) to the west, Paul Kagame is everywhere. By emancipating the country from the grips of Genocidaires in 1994, Kagame and his Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) have become entwined with the notion of the Rwandan nation-state. However, due to the fallible nature of the human spirit, the man who once pulled Rwanda up from the depths of genocide has become consumed by the senseless need for revenge as well as the corrupting nature of absolute power.

On July 15th, Rwanda is set to hold its Presidential and Parliamentary elections, and it is no secret that Kagame is set to secure for himself a fourth Presidential term. Since 2003, Kagame has never received less than 93 percent of the vote, receiving an unprecedented 98 percent of the vote in the nation’s 2017 election.

Kagame dominated the 2017 election after the country’s constitution, which outlines term limits for Presidents, was amended in 2015 to ‘reset the clock on terms already served,’ which in essence will allow Kagame to stay in power until 2034.

While being wildly popular with one’s voter base is not unusual, Kagame’s methods to remain wildly popular are unusual. According to Human Rights Watch, “Fourteen members of the unregistered Dalfa-Umurinzi opposition party and four journalists and critics are behind bars. Several are awaiting trial- some have been in pretrial detention for more than two years- and others have been convicted of offenses incompatible with human rights norms. Since the country’s last Presidential election in 2017, at least five opposition members and four critics and journalists have died or disappeared in suspicious circumstances.”

In 2010, Victoire Ingabire, the party President of Dalfa-Umurinzi, was arrested over her attempt to run in the country’s election. She was imprisoned for eight years, and spent five of those years in solitary confinement.

In July of the same year, Kayumba Nyamwasa, a former Rwandan Lieutenant-General who had fallen out with President Kagame, was shot in the stomach in South Africa. By 2014, there had been two more attempts on Nyamwasa’s life. That same year, Nyamwasa’s associate, Patrick Karegeya, who had once been involved in an opposition party with Nyamwasa, was found strangled to death in a Johannesburg hotel room. Although Rwanda denies involvement in the killing, the United States’ 2022 report on Rwanda outlines instances of “transnational repression against individuals located outside the country, including killings, kidnappings, and violence.”

Alexander Joe

Earlier this month, Diane Rwigara, the leader of the opposition People’s Salvation Movement (PSM) was informed by the Electoral Commission that she was unable to run in the country’s upcoming election due to her submitting the incorrect documents regarding previous criminal convictions.

Rwigara had also attempted to run in the 2017 election but was barred, with her and her mother arrested by the Rwandan police over allegations that they had forged signatures on Rwigara’s electoral documents and had attempted to incite an insurrection. Rwigara was acquitted of all charges in 2018, although political observers have noted that her latest barring is the likely result of her past criticism of President Kagame.

As a result, Kagame is running against just two other candidates, Frank Habineza of the Democratic Green Party, and Phillipe Mpayimana, an independent.

While the re-election of Kagame will ensure policy continuation, which is particularly important because Rwanda is the United Nation’s third largest police and troop contributor, but also because under Kagame, Rwanda is seen by the West as a ‘donor darling.’

A ‘donor darling’ refers to nations for which the West provides aid with minimal conditions attached, due to their history of responsible fiscal spending. A donor darling as defined by British political scientist Nic Cheeseman, “is a country that is in favor with international donors, either because it has closely followed their prescriptions or because the challenges that it faces are a particularly good fit with donor priorities.”

Currently, Rwanda receives aid from the United States, Germany, Japan and France, totalling $1.3 billion in 2021.

In 2023, Rwanda’s debt reached an estimated $8 billion, with an estimated GDP of $13 billion, the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio reached 68.6 per cent; with a debt-to-GDP ratio of 60 per cent seen as a healthy target. Nonetheless, Rwanda’s GDP grew by a remarkable 7.6 per cent in the first three quarters of 2023.

And while aid to Rwanda has enabled the county’s capital of Kigali to rapidly develop, with Kagame seeking to lift Rwanda to middle-income country status by 2035 and high-income country status by 2050, the nation’s civil society has been stunted, which is likely to impede Rwanda’s ability to develop in the future, in a time when Kagame no longer holds office. Despite these issues within the Rwandan domestic political sphere, the country remains one of Africa’s fastest growing economies, and it is the first country in the world with a female majority in Parliament.

Nevertheless, a question arises over why, despite Kagame’s long and well-documented history of human rights abuses, does the international community continue to support the reign of the RPF?

The answer is fourfold. First, the old saying ‘better the devil you know than the devil you don’t” remains painfully relevant to much of the West’s contemporary interactions with Rwanda, with world leaders more than aware of the impact regime change can have on regional stability. Second, the deployment of Rwandan troops to fight Islamic militants in Mozambique, anti-government rebels in the Central African Republic, and its bolstering of the UN mission in Sudan, have earned it international prestige as a peace enforcer, a characteristic that the West would like to see more of in Africa. Third, international guilt over the complete lack of a response to the 1994 genocide, to such a degree that Western militaries evacuated their own civilians out of the country while slaughters were taking place in the nation’s streets, has weighed heavy on the Western conscience and informed its relations with Rwanda since. And fourth, as recent political developments in nations such as Mali, Guinea, Burkina Faso, and Niger have shown, international condemnation and aid cuts have proven weak in bringing about change in a country’s domestic politics. The introduction of new players into the continent, such as Russia, that are willing to fill the shoes of the Western powers should an opportunity arise and without aid conditions based on human rights principles, makes it a more attractive partner to many African leaders who hold the term ‘African solutions to African problems’ dear.

A Long, Tangled History

Before colonization, no distinction was made between Rwanda’s Hutu’s, Tutsi’s, and the indigenous Twa. Only in the 1930s, when Belgium had assumed the administration of the country, did the colonial government begin issuing identity cards that distinguished Hutu from Tutsi and Twa. At the time, the Belgians had garnered a keen interest in eugenics and had attached themselves to the belief that Tutsis were closer to being Caucasian than Hutus, and thus placed Tutsis in economically superior positions. By the 1940s, Tutsis were favored in education, being taught in French, while the Hutus were taught in the country’s native Kinyarwanda.

By 1959, ethnic tensions boiled over, resulting in the Hutu Revolution, which caused many Tutsis to flee to neighboring nations, with Paul Kagame’s family fleeing to Uganda when he was just two years old.

In 1962, upon gaining independence from Belgium, Gregoire Kayibanda, an ethnic Hutu and founder of the Parti Du Mouvement De l’Empancipation Hutu, or PARMEHUTU, assumed the Presidency.

In 1973, Juvenal Habyarimana, Kayibanda’s Defense Minister took over power from Kayibanda through a coup d’etat, outlawed PARMEHUTU and introduced his own party, the Mouvement Pour Le Revolutionaire National Pour Le Development (MRND).

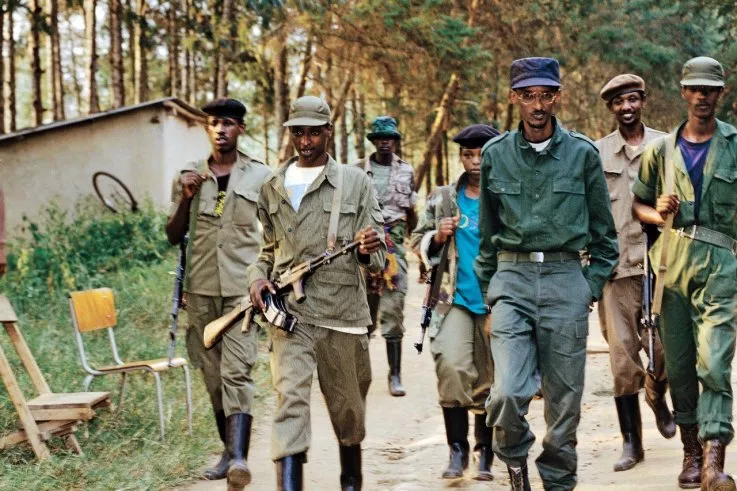

In Uganda, in 1987, exiled Rwandan Tutsi’s formed the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) under the leadership of Fred Rwigyena. At this time, Kagame was serving as Uganda’s Chief of Military Intelligence, fighting alongside Uganda’s current President, Yoweri Museveni, in the Ugandan Bush War.

Fred Rwigyena was killed during the RPF’s first attack against Habyarimana’s regime in October 1990, as a result, Kagame assumed command of the RPF.

Under Kagame, and between 1991-1992, the RPF conducted a guerilla war against Habyarimana’s forces, prompting Hutu youth militias, also known as the Interahamwe, to begin organizing. During this time, Rwandan radio stations such as Radio Rwanda and Radio-Televison Des Libre Milles Collines became propaganda tools, pushing the notion that Tutsis were inyenzi, or cockroaches.

In August 1993, after months of negotiations, the RPF and the Habyarimana’s Government signed the Arusha Accords in Arusha, Tanzania, in an effort to bring an end to the Rwandan civil war.

By October 1993, the UN deployed its mission to Rwanda, UNAMIR, to oversee the implementation of the Accords. The mission, under a ‘hands-off’ Chapter VI mandate, was under the command of Canadian Major-General Romeo Dallaire.

However, neither party appeared willing to disarm. In late October 1993, the Carnegie Commission on Preventing Deadly Conflict (CCPDC) issued a report claiming that lists of Tutsi targets had been drawn up by radical Hutu factions. In the Department of Peacekeeping Operations’s (DPKO) reply, Dallaire was told to avoid any action that would result in the use of force.

On December 27th, Belgian intelligence in the country reported that “The Interahamwe are armed to the teeth and on alert… each of them has ammunition, grenades, mines, and knives… they are all waiting for the right moment to act.”

By the next year, tensions in the country were palpable. On January 11th, Major Dallaire cabled the DPKO over the existence of a high-ranking Interahamwe member willing to act as an informant. The man claimed that he had been tasked with identifying all of Kigali’s Tutsis for extermination and was prepared to divulge the locations of the paramilitary group’s arms caches. The informant also claimed the Interahamwe were seeking to provoke the Belgian forces to create an opportunity in which they would retaliate and force the withdrawal of the remaining mission troops.

By February 22nd, reports of indiscriminate killings of Tutsis passed through Belgian intelligence, with Belgian peacekeepers claiming they “were helpless to stop the escalating violence.”

In early March, Belgian intelligence reported that an MRND member claimed that if the RPF resumed fighting, there would be a mass extermination of Tutsis, stating, “If things go badly, the Hutu will massacre them without pity.”

On April 6th, the trigger of the incoming genocide was found in the killing of Rwanda’s President Habyarimana and Burundian President Cyprien Ntaryamira, who was also an ethnic Hutu, when their plane was hit by a surface-to-air missile while coming in to land at Kigali airport. To date, the group to which the perpetrators of the missile attack belong remains unknown.

The next day, Rwandan Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana was killed alongside her husband and ten Belgian peacekeepers who were tasked with guarding her home.

The death of Agathe Uwilingiyimana opened the floodgates in the country, with an estimated 800,000-1,000,000 Tutsis and Hutu moderates slaughtered in 100 days by the nation’s various Hutu militas.

In the early stages of the genocide, France, Belgium, and the United States sent their militaries into the country to evacuate their nationals, leaving Rwandan civilians to fend for themselves.

On April 8th, the French government evacuated its civilians through ‘Operation Amaryllis’, under which its forces were ordered to “adopt a discreet attitude and a neutral behavior vis-a-vis the various Rwandan factions.”

From April 9th-10th, US Marines evacuated 240 US citizens by a series of overland convoys.

On April 13th, the Belgian government evacuated 425 of its citizens, returning later to evacuate the approximately 1,500 more still in the country.

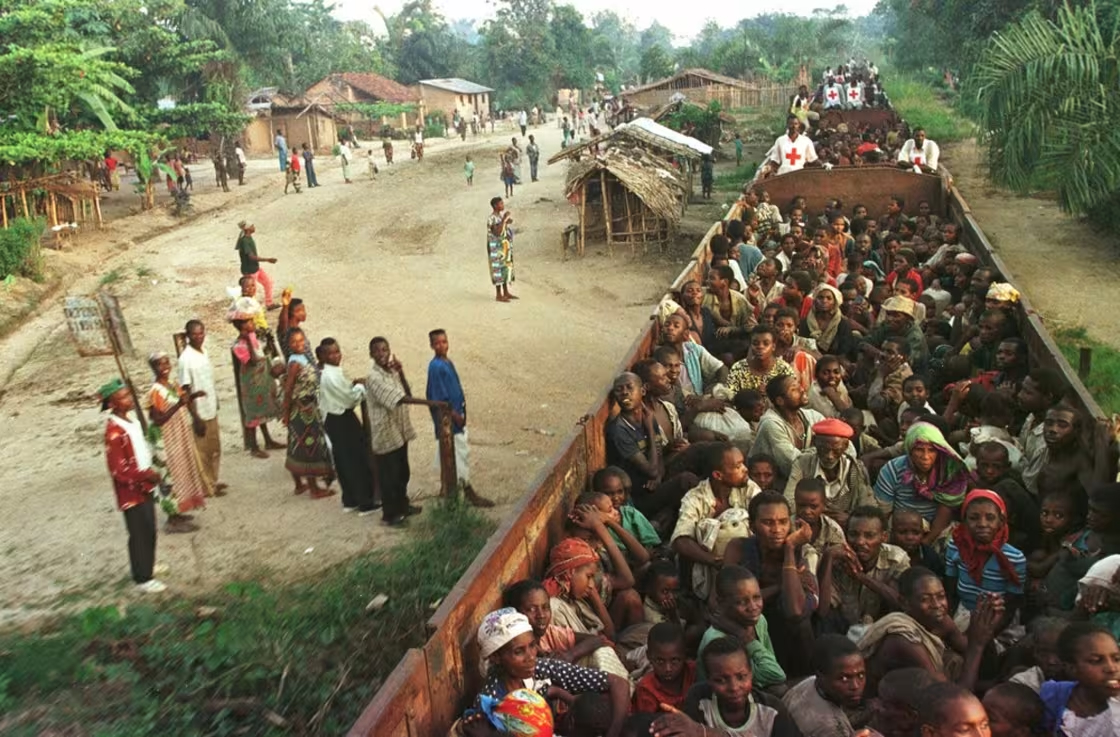

Almost exactly three months after the onset of the genocide, the RPF under Kagame captured the capital city of Kigali, making Kagame the country’s de facto leader. The RPF’s victory against the radical Hutu prompted an estimated two million Hutu to flee to neighboring countries, including some Interahamwe members.

By July 19th, the country had a new President in the form of Pasteur Bizimungu, who had appointed Kagame as his Vice President.

Revenge is a Dish Best Served Cold

Two years later, and convinced that many Interahamwe were living in Congolese refugee camps, Rwanda in 1996 invaded the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (then called Zaire), ushering in what became known as the First Congo War. Rwanda was joined by the forces of Uganda, Burundi, Angola, and Eritrea, who organized under the Allied Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo (AFDL) against the forces of Congolese dictator Mobutu Sese Seko. The conclusion of the war resulted in the ousting of Mobutu and brought in the Rwandan and Ugandan-backed Laurent Kabila in 1997.

By the late 1990s and most likely through the fear of becoming a puppet to Rwanda and Uganda, President Kabila ordered all remaining foreign troops out of the Congo, which impeded Rwanda’s plan to build up forces in the border areas it shares with the Congo to prevent the unlikely event of Hutu extremists returning to Rwanda.

Rwanda invaded the Congo again in 1998, in what would become the Second Congo War, during which, in 2000 President Bizimungu resigned, bringing Paul Kagame to power officially, although he had always maintained a strong influence over the country’s policy direction due to his position as VP and within the RPF. In the same year, Rwandan Hutus who had fled to the Congo founded the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) in September. In the contemporary period, Kagame uses the existence of this group as the reasoning behind his backing of the M23, a Tutsi-dominated rebel group operating in the Congo’s east.

In 2001, President Kabila was assassinated by a bodyguard, which pushed Kabila’s son Joseph, who assumed de-facto power to end the war, to officially assume power in 2006.

It is from here, at the end of the Second Congo War, with Rwanda’s intended border forces thrust back towards Kigali, that we begin to see a fear building in the consciousness of the Rwandan political elite. The experience of the genocide left a major mark on the minds of those who fought against it, particularly the mind of Paul Kagame, who has maintained a belief that the existence of Hutus in the Congo poses a threat to the existence of Rwanda. As a result, the academic Manuel Grajeda has referred to the first and second Rwandan incursions into the Congo as a “revenge genocide.”

Enter M23

The March 23 (M23) rebel movement is a paramilitary group of mostly ethnic Tutsis that is active in the Congo’s east, particularly in North and South Kivu. The group takes its name from a March 23rd, 2009, peace agreement signed between members of the National Congress for the Defence of the People (CNDP)—who had been waging an insurgency in the nation’s Kivu region—and the Congolese government.

In April of 2012, citing poor conditions within the armed forces (FARDC), approximately 300 soldiers, many of them former CNDP members, organized the M23 movement and began waging an insurgency against FARDC forces. By November 2012, the group had captured Goma, the capital of North Kivu, prompting Germany, the United States, the Netherlands, France, the United Kingdom, and the European Union to swiftly pull back their aid to Rwanda for their backing of the group.

As a result of the West’s economic punishment of Rwanda, the M23 pulled out of Goma and began demobilizing in November of the next year.

In May 2021, Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi signed an infrastructure and bilateral trade agreement with Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni. The agreement allowed for almost 140 miles of roads—the Mpondwe/Kasindi-Beni road, the Bunagana-Rutshuru-Goma Road, and the integration of the Beni-Butembo Axis—to connect the Congo and Uganda, facilitating both informal and formal cross-border trade between the two nations.

Rwanda’s Kagame, who once fought alongside President Museveni, most likely interpreted this development to be an attempt by Uganda and the DRC to undercut Rwanda’s role in the economy of the region, as trade flowing straight into Uganda from the Congo and vice-versa would negatively impact Rwanda.

In November of that same year, the M23 remerged in the Congo’s east, and began waging an insurgency that continues to this day, displacing hundreds of thousands of civilians, and killing thousands more.

In April of 2022, the DRC was integrated into the East African Community (EAC) further threatening Kagame’s imagined hold over the region. Unsurprisingly, in December of the same year, a UN report which contained aerial images of sophisticated surface-to-air missile launching systems utilized by the M23, found that the M23’s uniforms identically resembled those of the Rwandan Defence Forces (RDF). The report also noted the unusual organization of the M23, claiming the rebels march in 500-man columns, similar to that of a conventional fighting force.

By this time, the Hutu FDLR, who once had upwards of 6,000 members in 2007, had diminished to a small fighting force of an estimated 1,000-2,000 members, pulling into question the legitimacy of Kagame’s belief in the ‘Hutu threat’ in the Congo.

As posited by British journalist Michela Wrong, “Kagame both denies backing the M23 and routinely implies that the Hutu extremist group has forced his hand—rhetoric that silences unhappy allies and reminds Rwandans what they owe him for defeating the country’s genocidal government three decades ago.”

Furthermore, various analysts have made the claim that Kagame’s motives in the DRC have changed in recent years, triggered by the DRC-Uganda infrastructure deal. Allegations surfaced that Rwanda, under the cover of M23 operations, had begun siphoning various minerals from the DRC’s illustrious mines into Kigali to be sold to nations such as the United Arab Emirates and multinational companies like Apple.

And while, officially, Rwandan exports to Dubai and Apple are legal, there have been discrepancies between Rwanda’s on-paper gold exports and its actual gold exports that suggest illicit activity.

In June 2019, a United Nations group of experts on the DRC addressed the UN Security Council stating, “Rwanda declared gold exports of 2,163 kg (2.3 tons), while the United Arab Emirates officially imported 12,539 kg (13.8 tons) from Rwanda during the first nine months of 2018.” These discrepancies continue, with the DRC Minister of Mines, Antoinette N’samba stating on May 15th that all mining products from Rwanda should be considered ‘blood minerals’ because their sale ostensibly supports the conflict in the east.

The comments came after the M23 captured one of the country’s largest tantalum mines earlier in May, prompting the DRC’s international lawyers to announce on May 22nd that they had found additional evidence that allegedly points to the electronics company, Apple, sourcing its minerals from conflict areas, specifically, areas in the east of the Congo.

Behind the Kagame Mask

Kagame, in recent years, has only become more emboldened to pursue his desired position domestically and in wider Eastern Africa, even as his mask begins to slip in the international arena.

In September 2023, the United States recognized Rwanda as being complicit in the recruitment or use of child soldiers in relation to its support of the M23. While in mid-February 2024, the United States Department of State officially announced its recognition of Rwanda as a backer of M23.

“The United States strongly condemns the worsening violence in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) caused by the actions of the Rwanda-backed, US- and UN-sanctioned M23 armed group, including its recent incursions into the town of Sake. This escalation has increased the risk to millions of people already exposed to human rights abuses including displacement, deprivation, and attacks. We call on M23 to immediately cease hostilities and withdraw from its current positions around Sake and Goma and in accordance with the Luanda and Nairobi processes. The United States condemns Rwanda’s support for the M23 armed group and calls on Rwanda to immediately withdraw all Rwanda Defense Force personnel from the DRC and remove its surface-to-air missile systems, which threaten the lives of civilians, UN and other regional peacekeepers, humanitarian actors, and commercial flights in eastern DRC,” said State Department Spokesperson Matthew Miller.

Not only does Rwanda’s actions in the DRC violate the principles of the East African Treaty, which emphasizes respect for the rule of law, democracy, and human rights, but also the measures he has taken inside his own country to secure his rule signal that the once-benevolent emancipator has, as many before him have, fallen victim to the corrupting nature of power.

So, What Now?

With the Rwandan elections set to take place in less than a month, Kagame has done as many authoritarian leaders before him and reshuffled his cabinet, appointing Olivier Nduhungirehe as his new Foreign Minister and General Aimable Havugiyaremye as his Secretary-General of National Intelligence and Security. Regular shuffles of cabinet members allow Kagame to maintain a hold over his politicians, who stay in line due to the ever-looming threat of unemployment. This tactic also serves to quell dissent and reminds his politicians that Kagame alone is the government.

A question arises over how a man who was once a nation’s savior can so quickly be drawn in by the allure of authoritarian power consolidation. But the answer lies in our current international order’s inherent geopolitical and ethical complexities. Western donors are unwilling to economically punish Rwanda for its misgivings, even though it had been a proven method in the past, due to the fragile state of Africa in the current day. An ever-patient Russia, willing to capitalize on Western miscalculations as seen in Niger, Mali, Guinea, and Burkina Faso, has forced the West to approach the issue of human rights abuses in Africa in a far different manner. However, the effect of international guilt as a result of Western inaction during the genocide has also played a part in creating the Kagame we know today.

Nonetheless, Kagame’s achievements over the past 30 years cannot be understated. Rwanda is a growing economic powerhouse, with a level of female representation in government that is not seen in many other African nations. These facts raise another question: Does a country need to be democratic to develop sustainably?

While many scholars have put forth their views, the commonly accepted notion is that a vibrant civil society, political pluralism, and journalistic freedom encourages citizens to engage with their compatriots on issues that directly affect them, which increases innovation and problem-solving at the community level. While there are highly developed societies under authoritarian rule, a stunted civil society creates political apathy to such a degree that when an authoritarian leader dies, as all are destined to, the country is often plunged into years of political and societal disorganization.

In the case of Kagame, it seems that the renowned leader has failed to accept that there will one day be a Rwanda without Kagame. Upon gaining power in 2000, he abolished the office of the Vice President, thereby eliminating a succession plan. And despite his speaking on his ‘inevitable’ retirement in early 2023, Kagame’s continued efforts to repress opposition parties signals that his efforts to develop the nation under his and the RPF’s leadership in the short-term will only serve to handicap the country in the long-term.