Four hostages, two of whom belong to Colombia’s Prosecutor’s Office, were released by a splinter group of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, known as the Estado Mayor Central (FARC-EMC), on Sunday, following a previous stall in talks regarding the hostage’s release.

Released After Months of Holding:

Three of the four had been held by the FARC-EMC since late April, and were captured while the trio were en route to the municipality of Popayan in Cacua when they were ambushed and taken captive in a rural area known as Dominguillo just outside of Santander de Quilichao, another municipality. Two of these three were prosecutors, Gerson and Bethy Amanda, who were captured alongside a “companion” and possible family member, María Yeni Ruiz. The fourth hostage was identified by the FARC alongside the Colombian Army as a professional soldier by the name of Yiner Kevin Noscue Largo.

Damos la bienvenida a la libertad a nuestro soldado profesional Yiner Kevin Noscue Largo y agradecemos a la misión de verificación de la @MisionONUCol y @DefensoriaCol, quienes intercedieron por su vida e integridad y la de los miembros de la @FiscaliaCol.

Así mismo,…

— Ejército Nacional de Colombia (@COL_EJERCITO) May 12, 2024

The FARC previously stated that operations conducted by the Colombian military in order to free the hostages and damage the FARC-EMC in the region had endangered the lives of the hostages, reiterating this claim in their newest statement, which claimed “they (the hostages) had to endure the difficulties that come with breaking the ceasefire and declaring “total war” against our organization.”

The armed group further stated that the operations conducted by the Colombian military exacerbated the wait for the release of the hostages, stressing that “militarist sectors in Colombia prevented these minimum conditions (for their release) from being developed.”

These demands included the halting of military operations against the FARC-EMC in Cauca, a region known for its large FARC presence, for 48 hours. This demand would ultimately be denied by the Colombian military, with the Colombian Ministry of Defense stating that “the area they request is too large.”

The hostage release further follows escalating tensions within Cauca; just last week, four soldiers were killed in a military operation against the FARC, while two other soldiers were killed in an ambush launched by the armed group.

The FARC thanked both the United Nations mission in Colombia and the Colombian Red Cross for both facilitating the release of the hostages and the UN’s action in acting as a channel of dialogue between the government and the armed group. The group assured the family of the hostages that those held were safe and “had all the conditions for food, health, clothing, and safety.”

The hostages were released to the Colombian Red Cross and later transported to the proper authorities, while their release was confirmed by President Gustavo Petro on X.

Han sido dejados en libertad los miembros de la fiscalía y un soldado secuestrados por el EMC en el Cauca. pic.twitter.com/zyBXdagULj

— Gustavo Petro (@petrogustavo) May 12, 2024

The FARC concluded their statement by stressing that the Colombian government’s refusal to reenter peace talks “leads nowhere.”

“The hasty decisions it (the Colombian government) made against the FARC-EP that led to the breakdown of the ceasefire, the constant accusations against our commanders, and its vain attempt to hold a dialogue table with a minority that is not part of the FARC-EP and does not represent even 5% of our guerrilla force is a bad path that it took, and that is not going to ensure the objectives that we had jointly proposed since we began that process of dialogue, which was nothing more than setting us on the path of a political and dialogue solution to overcome the structural elements that generated the conflict in Colombia.”

Analysis:

The release of the hostages will act as a major victory for both Petro’s administration and the Colombian military, as concerns regarding the criminal operations of various armed groups within Colombia have risen amid the president’s controversial “total peace” plan. This plan for “total peace” is an effort by Petro to end the nearly 60-year-long civil struggle between the Colombian government and the various politically motivated armed groups across Colombia in a conflict that has led to the deaths of an estimated 450,000 people.

The release of the hostages may boost the president’s popularity in the polls; however, it is equally possible that critics and dissenters may attack Petro for, in some people’s eyes, allowing the FARC to further their power amid the previously negotiated ceasefire.

FARC:

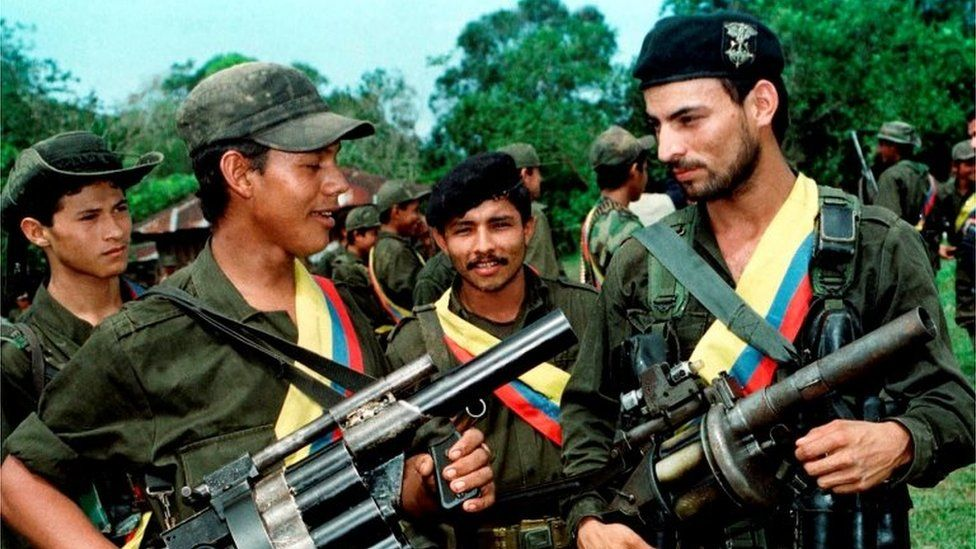

The FARC, otherwise known as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, were originally leftist guerillas dedicated to bringing class revolution to Colombia during a period in the nation’s history known as “La Violencia,” otherwise known as the Violence. This period followed the assassination of the Liberal Party’s leader and presidential frontrunner, Jorge Eliecer Gaitan, in 1948, an assassination that would throw Colombia into chaos.

After his death, leftists in Bogota began what is known as the Bogotazo, a massive riot that quickly expanded across Colombia, leading to La Violencia. A number of right-wing paramilitary organizations and leftist guerilla groups would be formed during this period of Colombian history.

One of the most well-known was the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC. The group would find its formation after a failed attack in 1964 by the Colombian military on what was known as a self-defense community, one of a number of communist-held areas in rural Colombia. Despite the communists only having 48 active fighters opposed to the 16,000 Colombian soldiers, the group would survive the attack and escape to the nearby mountains where the FARC would be formed.

Since then, the FARC has operated as rebels, launching guerilla attacks on military convoys and strategic targets. Despite originally being made up of only 48 fighters, the group’s ranks would swell to the hundreds in later years. For much of its early history, the FARC would be limited to small-scale guerrilla encounters with government forces, but after what has been coined the “Coca Boom,” a period in which the production of cocaine skyrocketed, the group found itself with more funds to allocate to their operations.

The FARC would expand their operations into urban Colombia following the Seventh Guerilla Conference in 1982, largely due to their increase in funds. The group would also begin to send promising troops to the USSR and Vietnam for advanced training.

The FARC would eventually agree to a momentous ceasefire with the government in 2016, which would see the bulk of the FARC disarmed and disbanded. Despite the ceasefire, however, a number of members of the FARC continued their operations against the government and the people of Colombia. These groups would label themselves as “fronts,” a leftover from the group’s original structure, with two factions emerging.

The first, the FARC-EMC, would be founded by Gentil Duarte, who was sent back to Colombia amid the peace conference in Cuba due to Ivan Mordisco separating himself and his soldiers from the peace process. The two would send out messengers to a number of commanders of the FARC’s other fronts, seeking to unite them into one body and continue the organization’s armed struggle against the government. This would succeed, and in 2017, Duarte and Mordisco would announce the birth of the FARC-EMC.

Their main rival would prove to be the Second Marquetalia, which was formed by a number of former FARC commanders, many of whom previously accepted the ceasefire but would rearm in 2019. The group’s main territory encompasses the Venezuelan-Colombian border, where the FARC has historically enjoyed a great deal of protection from authorities in Venezuela. The Second Marquetalia would even come into conflict with another dissident faction of the FARC. This faction, known as the 10th Front, had refused to support the leaders of the Second Marquetalia, who had attempted to pull rank on the dissidents in Venezuela following their rearmament. Following the refusal, the 10th Front would face direct action by Venezuela’s military, in what Insight Crime reports was an attempt to grant further power to the Second Marquetalia.