Overview:

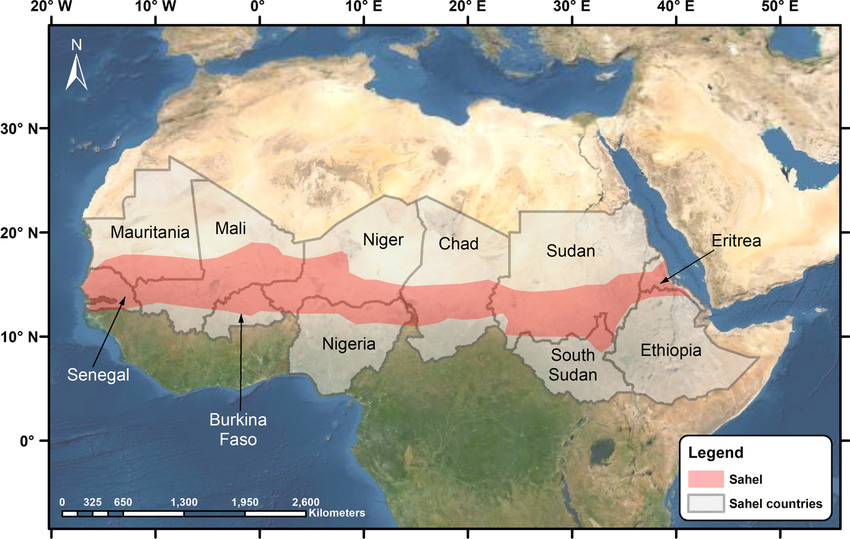

In November 2020, Secretary-General of the United Nations Antonio Guterres described the Sahel—the semi-arid area draping across Senegal in the west all the way to Eritrea in the east—as a “microcosm of cascading global risks converging in one region.”

The Sahel separates sub-Saharan Africa from the deserts of northern Africa and, in recent years, it has become a hotbed of separatist and Islamic militancy, as well as bearing the brunt of desertification as a result of low rainfall.

Source: Al-Saidi, Mohammad & Saad, S.A. & Elagib, Nadir. (2022). From scenario to mounting risks: COVID-19’s perils for development and supply security in the Sahel. Environment, Development and Sustainability.

Mali, Africa’s 8th largest nation and the continent’s 4th largest gold producer, has found itself embroiled in civil conflict just three years after independence. Despite being well endowed with vast caches of natural resources such as iron ore, uranium, manganese, lithium and limestone, 68.3 percent of the country remains multidimensionally poor, according to recent data from the United Nations Development Program.

With these facts in mind, Mali appears as another African nation blighted by the ‘resource curse’, the phenomenon by which nations with an abundance of natural resources find themselves less developed, less democratic, and with less economic growth than nations that do not hold such resources.

However, the position Mali finds itself in today can be understood to be the result of two major factors. First, its geographical location, as it constitutes part of the Liptako-Gourma subregion alongside Burkina Faso and Niger, two nations which have also found themselves victims of a series of coup d’etats in recent years, and second, its continuous battle against the Tuareg people of Mali, with each ceasefire agreement brokered in the past disregarding the key facets needed for enduring peace, namely, development, trust in government, and participation in the political process.

In seeking to understand Mali’s current crisis, one must take a macro approach, viewing the contemporary history of the country as a prime example of the domino effect. Exogenous factors, particularly NATO’s 2011 intervention in Libya, set in motion a series events which has seen the Tuareg separatists joining forces with Islamic militants “who split and coalesce as new opportunities arise” as posited by Walther, Leuprecht, and Skilicorn.

Currently, the nation is awash with non-state and state actors, each with competing objectives. Russia’s Wagner group, which was recruited by the Malian junta in 2021, bolsters the military regime of Colonel Assimi Goita in exchange for resource concessions. The group has also aided the Malian army (FAMA) in its fight against insurgents in the country’s north. Currently, the biggest players in the north are Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM)—an umbrella group of Islamic militant organizations such as Ansar al-Din, al-Mourabitoun (MUJAO), Katiba Macina, and al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)—the Islamic State in the Greater Sahel (ISGS), and the Coordination of Azawad Movements (CMA), an umbrella group of Tuareg separatist movements.

Since the onset of the ‘Malian War’ in 2012, various elements of each group have fought together and fought against each other.

Currently, JNIM and ISGS are embroiled in conflict over ideological and operational differences which began in 2019, while in 2012, the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), a key Tuareg rebel group which forms part of the CMA, joined forces with Ansar al-Din (who forms part of JNIM) to capture the cities of Kidal, Asongo, and Bourem, before turning their arms back against each other. Thus, one begins to see the complexity of the Malian conflict as the result of the inherent complexity of contemporary international politics.

Furthermore, the human cost of Mali’s conflict is high, with the International Rescue Committee recording the internal displacement of more than 390,000 civilians. In neighboring Mauritania, Malian refugees constitute more than one-fifth of the population of its Hodh Ech Chargui border region. This is largely owed to the brutal counter-insurgency tactics utilized by FAMA and the Wagner Group. For example, in March 2022, Wagner and FAMA elements undertook a five-day assault on the south-central village of Moura in an attempt to eradicate Islamic militants. By the end of the assault, 300 civilians had been killed.

The Malian junta’s announcement in January that it would no longer honor the 2015 Algiers Accord signed with Tuareg separatists to end the Malian war has resurrected the historical dimension of the crisis. As a result, in April, Mauritania conducted a series of live fire military drills near its south-eastern border with Mali in response to the entry of FAMA and Wagner forces into the Mauritanian villages of Fassala and Madallah while pursuing Tuareg rebels.

Consequently, in late May, Tuareg rebels formed a new alliance, the Permanent Strategic Framework for the Defense of the People of Azawad (CSP-DPA), under the leadership of Bilal Ag Acherif. Acherif served as the Secretary-General of the MNLA when the group made major gains against the Malian government in 2012. This development signals that conflict in the country is likely to escalate to levels similar to that of Liberia during its civil conflicts between 1989-2003.

Geography:

Mali is a large, landlocked nation with its population of almost 24 million highly dispersed. Much of the country’s economic activity is confined to the areas near the Niger river, as 65 percent of its land is classified as desert or semi desert. As aforementioned, development remains low, and poverty is high, particularly in the northern desert areas.

Mali also forms part of the Liptako-Gourma subregion alongside Burkina Faso and Niger. The Liptako-Gourma subregion has, in recent years, become a hotbed of militancy due to the three nations’ poor border enforcement, enabling arms to proliferate and militants to roam, for the most part, unaccosted between borders.

The Tuaregs:

The Tuareg people are a group of semi-nomadic herders found in northern Mali, the border regions of Niger, Burkina Faso, Algeria, Mauritania and Libya. They speak a Berber-based language, either Tamashek, Tamajaq, or Tamahaq depending on where they live. During the colonization period, the Tuareg people became fragmented by the borders drawn by the French, which impeded the Tuareg desire for an independent state.

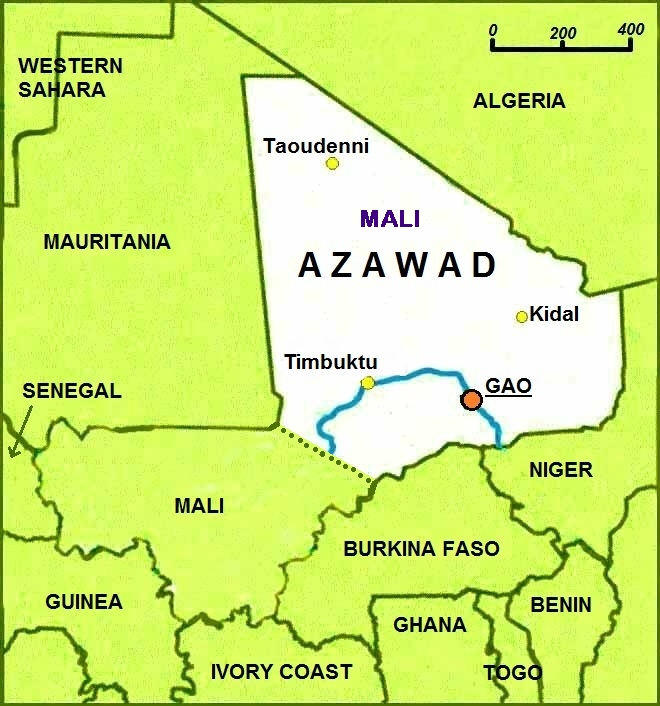

The idea of an independent Tuareg state, named Azawad, was conceptualized to encompass the areas where the Tuaregs reside, which is much of northern Mali. Azawad is thought to translate to mean the ‘land of transhumance’ with transhumance being a term which describes the seasonal movement of livestock, or nomadism.

Conflict 1:

Upon gaining independence from France in 1960, an independence movement emerged among Mali’s Tuaregs, who, on May 14, 1963, and under the leadership of Zeyd Ag Attaher, took up arms against the government.

By August 15, 1964, the rebellion was declared as over by the Malian government, but not before 5,000 civilians had fled to Algeria.

Conflict 2:

Tensions between the Tuaregs and the Malian government flared again in June 1990 when rebels organized under the Popular Movement of Azawad led by Iyad Ag Ghali, a Tuareg Islamist militant from Mali’s Kidal region who later went on to found Ansar al-Din. In the same month, Tuareg rebels attacked three towns in northern mali, triggering the second Tuareg conflict.

A month after the attack, the Malian government declared a state of emergency, with Algeria in 1991 stepping in to mediate a ceasefire agreement between the government and another Tuareg group, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Azawad (FPLA). However, fighting continued.

Between January and March 1992, Algeria had mediated three rounds of negotiations between the government and another Tuareg group- the Unified Fronts and Movements of Azawad (MFUA).

In April 1992, MFUA and the Malian government signed the National Pact in Bamako, which brought an end to the conflict and promised increased investment and development in the north. However, Malian troops did not withdraw from the north after the signing of the pact and Tuareg rebels did not demobilize.

In February 1993, the government agreed to integrate former MFUA militants into the Malian army after negotiations mediated by Algeria.

Conflict flared again in June 1994, when militants organized under the Arab Islamic Front of Azawad (FIAA) attacked a military base in Niafunke in central Mali.

A year later, the FIAA agreed to cease military operations against the government. By this time, however, an estimated 2,500 civilians had been killed and approximately 150,000 Tuaregs fled to neighboring countries.

By May 1997, the United Nations claimed 102,429 Malian refugees who had fled during the conflict had been repatriated.

Conflict 3:

In May 2006, Tuareg rebels who had reorganized under the Democratic Alliance for Change (ADC), led by Ibrahim Ag Bahanga, attacked military barracks in Kidal and Menaka, triggering the third phase of the conflict.

Algeria attempted to mediate negotiations between the ADC and the government in July, but the provisions were rejected by Bahanga.

In February 2007, Algeria secured a disarmament agreement between the two parties, but fighting continued.

By July 2008, the ADC and the Malian government signed a ceasefire agreement, bringing an end to ADC operations.

Another rebel group in which Ibrahim Bahanga held a leadership position, the Tuareg Alliance for Change (ATNMC), attacked a military base in Nampala, re-igniting the conflict.

The last ATNMC base was overrun by the government in February 2009, leading the President of Libya, Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, to broker a peace agreement between the warring parties late in the year.

The peace deal prompted some 4,000 Tuareg militants to head to Libya, where they were incorporated into Gaddafi’s security services as ‘mercenaries’.

Post Conflict Phase 3:

In March 2011, a coalition of NATO states militarily intervened in Libya as sanctioned by Security Council Resolution 1973 in response to the Libyan authorities ‘failure to comply with Security Council Resolution 1970’ which imposed an arms embargo on the country as well as a travel ban and asset freeze on designated individuals in response to the escalating Libyan civil war.

In October of the same year, another Tuareg rebel group, the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), was established by Ag Mohamed Najem.

Four days later, in Libya, Colonel Gaddafi was killed by rebel forces after the battle of Sirte, forcing many of his former security personnel to return to their countries. This included many Malian Tuaregs.

Conflict 4:

In January 2012, the MNLA attacked Menaka, Aguelhok and Tessalit, triggering the ‘Malian War.’ Two months later, the government had struggled to make gains against the rebels, prompting dissatisfied Malian military personnel to depose President Amadou Toumani Toure on March 21st.

Just nine days after the ousting of President Toure, the MNLA, in conjunction with al-Qaeda-linked militant group Ansar al-Din, captured the towns of Kidal, Asongo, and Bourem. In early April, having made significant gains, the MNLA announced its intent to end hostilities against the government.

By April 6, the MNLA declared the independence of northern Mali, or Azawad, with the declaration quickly rejected by the European Union, the African Union, and France.

In mid-2012, the Tuareg desire for an independent state quickly started to come undone as the result of increasing incursions by the Islamic militant groups that had just months before helped them capture strategic cities.

The Undoing of the Tuareg Independence Movement:

In June 2012, the MNLA clashed with Ansar dine in Kidal, and by the end of the month, militants part of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) had pushed the MNLA out of Gao city.

Two months later, after immense pressure from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Mali’s interim military government reliquinshed power and a new civilian government was implemented under President Ibrahim Kieta.

The MNLA’s last stronghold, Menaka, was captured by Islamic militants in November, prompting the MNLA’s leadership to abandon its independence declaration and enter negotiations with the new Malian government.

As a result of the country’s deteriorating security environment, in January 2013, the African-Led International Support Mission to Mali (AFISMA) was deployed at the same time Tuareg militants under the Islamic Movement of Azawad (MIA) captured Kidal, Tessalit, and Khalil from Islamic militants.

On April 25, AFISMA transferred its authority to the incoming United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), which was tasked with supporting Mali’s political processes and performing a number of security-related tasks.

A month later, the European Union established its training mission in Mali (EUTM) to strengthen the capacity of Mali’s armed forces in its fight against Islamic and separatist insurgency.

By June 2013, an approximate 447,000 civilians had been displaced, and the MNLA and the Malian government began negotiating an ECOWAS mediated ceasefire.

With clashes continuing in February, a summit between Niger, Burkina Faso, Chad, Mauritania, and Mali produced the G5 Sahel, an intergovernmental organization focused on promoting development and security among Sahelian nations.

In August 2014, France launched its ‘Operation Barkhane’ counterinsurgency mission in the country, followed by the founding of the Coordination of Azawad Movements (CMA) in October, an umbrella organization of Tuareg rebel groups.

Early the next year, Katiba Machina, an al-Qaeda affiliated Islamic militant group was founded in the country.

Despite these developments, the CMA and the Malian government signed the Algiers Accords, which brought an end to the conflict in May 2015. That same month, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahel (ISGS) was founded.

By the end of the conflict, thousands of civilians had been displaced, with many fleeing to neighboring nations. While the wave of newly-formed Islamic militant groups prompted the United States in 2016, to begin a military presence in neighboring Niger at Airbase 201, from where it could conduct drone strikes.

Almost a year after the US began its military presence in Niger, in March 2017, Ansar al-Din, AQIM, and al-Mourabitoun, also known as the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Afric (MUJAO), formed the militant umbrella group Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam Wal-Muslimin (JNIM) to ‘expel and resist non-muslim occupiers.’

In a testament to the importance of the Sahel to regional and international stability, the Sahel Alliance was formed in July 2017 with priority areas in agriculture, energy, governance, education, and decentralization. After its creation, the African Development Bank, Canada, Denmark, the European Investment Bank, the European Union, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom, United Nations, the United States, and the West African Development Bank had all joined as full members.

The Domino Effect:

Receiving 67.16 percent of the vote in Mali’s 2018 election, President Ibrahim Keita, who had been in power since 2013, remained in power, and despite claims of election irregularities the UN Security Council announced it ‘welcomed the results.’

The next year, reports began to surface of clashes between formerly aligned JNIM and ISGS militants, adding another dimension to the already complex conflict.

In quick succession, the European Union deployed its French-led ‘Taskforce Takuba’ in conjunction with G5-Sahel partners to tackle the insecurity plaguing the Liptako-Gourma region.

Reminiscent of the nation’s 2012 coup, in August 2020, President Keita was deposed by the Malian military for his failure to contain the country’s insurgencies. Bah N’Daw was appointed as interim President while Colonel Assimi Goita was appointed to the position of Vice President.

The next year, in May, Goita led a mutiny against President N’Daw and assumed power.

In response to the country’s spiraling security crisis, and in line with previous deployments, Russia’s Wagner Group entered the country in December 2021 to aid in ‘coup-proofing’ Goita’s junta and enage in counter-insurgency operations.

France and Taskforce Takuba, in February 2022, announced their intention to withdraw from the country, creating a security vaccum Wagner was all too willing to fill.

Three months later, in May, Mali terminated its defense cooperation treaty with France, the mandate providing for EU operations in the nation, and pulled out of the G5-Sahel.

As a result of the spread of Islamic insurgency in the region, Burkina Faso fell victim to a coup in September, bringing an end to the interim Presidency of President Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba and placing Captain Ibrahim Traore in power.

Intentional international isolation has emerged as a common phenomena seen in other nations where Wagner has a large presence such as the Central African Republic. This is likely to prevent international actors from reporting on the activities and human rights abuses committed by Wagner forces as well as the Malian armed forces.

In June 2023, the Malian junta called for the withdrawal of MINUSMA—which had been labeled the UN’s second most dangerous peacekeeping mission—from the country.

A month later, on July 26th, Nigerien President Mohamed Bazoum was removed from power, with General Abdourahamane Tchiani assuming his position.

With the three nations who form the Liptako-Gourma subregion all under military rule and all grappling intense Islamic insurgencies, the three Juntas announced the creation of the ‘Alliance of Sahel States’, a mutual defense pact, in September 2023.

Most recently, and in somewhat of an impulsive move, the Malian junta announced the end of the 2015 Algiers Peace Accord with Tuareg rebels and in the same breath denounced the ‘proliferation of unfriendly acts and instances of hostility by Algeria,’ its key mediator in the Tuareg conflicts.

Conclusion:

A variety of factors have contributed to the position Mali finds itself in today. In terms of its now resurrected conflict with the Tuaregs, and as posited by Teresa Noguerira Pinto, distrust between parties, excessive international intervention, and unrealistic goals have prevented the Algiers Accord from being successfully implemented.

In addition, the lack of meaningful dialogue with the Tuaregs, low faith in government, and underdevelopment has not only transformed Mali and the Liptako-Gourma into a ‘militants paradise’ but has also provided the Malian junta and Wagner forces with Casus Belli for its brutal attacks on civilians, as seen through the Moura massacre.

Mali’s vast natural resources have also provided Wagner a reason to solidify its presence in the country, as gains made against rebels provides access to previously rebel-held mines. In November 2023, Wagner and Malian army forces captured the Tuareg stronghold of Kidal, and in February 2024, Wagner secured access to its first artisanal gold mine in north-eastern Mali. Two months later, Mali announced it would begin cooperating with Russia to begin increasing its gold, oil, gas, lithium, and uranium production.

Thus, one begins to understand that major international dialogue is required to address the Sahel’s insecurity. However, in line with the theme of ‘self-sufficiency’, the Sahel’s juntas have turned to Russia, who is seen as the least likely to meddle in the nations’ domestic politics insofar as it is able to continue receiving resource concessions.

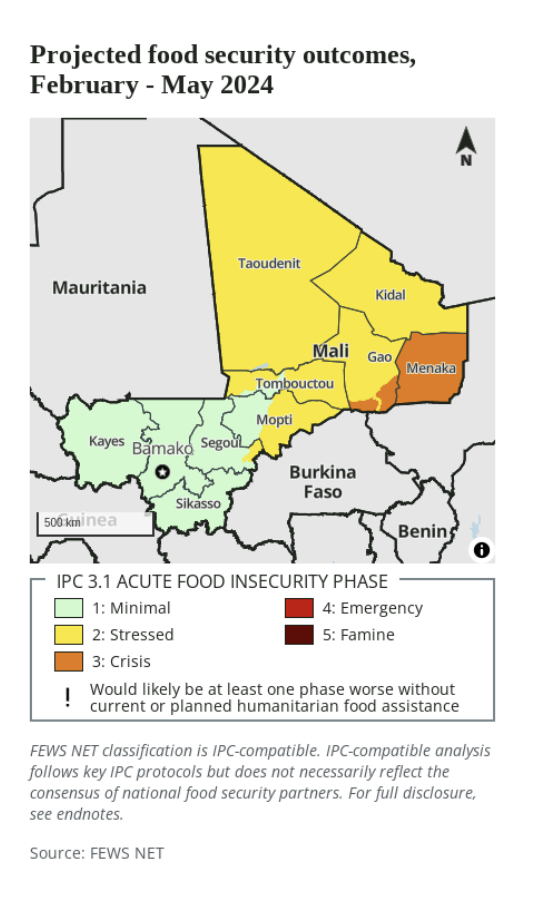

This shift away from the West has come at the detriment of the country’s civilian population, which is at risk of attack from Islamic militants, Wagner forces, the Malian armed forces, as well as separatists. In addition to the threat of violence, Malian civilians are grappling with drought-induced food insecurity. In 2019, before the ousting of President Keita, the country was ranked 184th out of 189 nations in the United Nations Human Development Index. The Famine Early Warning Systems Network has stated that despite it being harvest season in central and northern Mali, much of the two regions are suffering from acute food insecurity, with Menaka in ‘crisis’ phase.

Furthermore, the creation of the Alliance of Sahel States’ mutual defense pact has done little to address the key drivers of insurgency in the region such as climate change, low development, low political participation, and low trust in government.

Ethnic fragmentation, in the case of the Tuaregs, is a key example of a state in crisis.

It is likely that before the situation in the Sahel will improve, it will deteriorate far beyond what is being seen now.

As military juntas are known for being answerable to no one, what the international community should focus on now is the welfare of the Sahel’s civilians, who have, for many years, been disregarded as mere statistics.