Bosnia and Herzegovina, often referred to simply as Bosnia, is nestled in the heart of the Balkans, marked by centuries of coexistence and conflict among various ethnic and religious groups, including Bosniaks, Serbs, and Croats.

This article aims to provide an insight into Bosnia’s multifaceted identity, political system, and contemporary political challenges. From its Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian legacies to the devastating conflicts of the 20th century, Bosnia’s story is one of resilience, diversity, and ongoing struggle for stability and unity.

Historical background

Bosnia was established as a medieval kingdom in the 12th century, and later fell under Ottoman rule in the 15th century. This introduced Islam and significantly altered its cultural landscape. Ottoman influence lasted until the late 19th century, when Bosnia became part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, incorporating Western European cultural and administrative influences.

Following World War I, Bosnia was incorporated into the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, which was later renamed Yugoslavia. This multi-ethnic federation aimed to unify various Slavic groups, including Serbs, Croats, and Bosniaks, under one state.

Yugoslavia became a communist state under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito following World War II. Tito’s Partisans, a communist resistance group, fought against Axis occupation and emerged as the dominant force in Yugoslavia by the end of the war. In 1945, they abolished the monarchy and established the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia, with Tito as its leader. Differing from the Soviet model, Yugoslavia under Tito pursued a form of socialism that allowed for economic decentralization and autonomy within its constituent republics. This stance led to the Tito-Stalin Split in 1948, marking Yugoslavia’s independence from Soviet influence and aligning it with the Non-Aligned Movement during the Cold War. Tito’s governance helped maintain unity and stability in the ethnically diverse federation until his death in 1980.

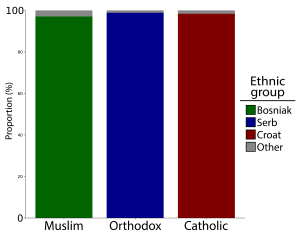

The death of Tito marked the start of rising nationalism, closely tied to familial religious backgrounds in the region. Typically:

- Serbs are Orthodox

- Croats are Catholics

- Bosniaks are Muslims

- Bosnians refer to all inhabitants of Bosnia

The causes for the fall of Yugoslavia are complex and remain widely debated. What is certain are the conflicts they led to, with the Bosnian War (1992-1995) being particularly devastating for the country and its populations.

The Bosnian War

Marked by severe ethnic conflict among Bosniaks, Serbs, and Croats, it led to widespread atrocities and to the concept of ethnic cleansing becoming globally recognized.

The war began after Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence from Yugoslavia, leading to the mobilization of ethnic Serb forces aiming to maintain the integrity of the state. This was met with resistance from Bosniak and Croat forces, resulting in a multi-sided war.

As mentioned, the conflict witnessed numerous ethnic massacres, the most notorious being the 1995 Srebrenica massacre, where Bosnian Serb forces executed over 8,000 Bosniak men and boys. However, all ethnic groups endured significant hardships and displacement: Serb civilians were killed in the Kazani pit by Bosniak forces, and Croatian civilians suffered the same fate during the massacre in Uzdol as part of the Republic of Bosnia’s Operation Neretva ’93.

The profound severity of the conflict is evident through two illustrative instances. The war witnessed the longest siege in modern warfare, the Siege of Sarajevo, where the city was encircled by Serbian forces for nearly four years and led to thousands of civilian deaths and widespread destruction. It also saw the last bayonet charge in history, conducted by French Foreign Legionnaires to dislodge Serbian forces from the opposite side of a bridge near Sarajevo.

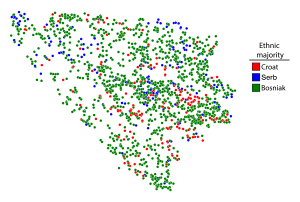

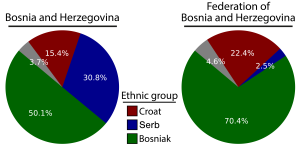

As we can see, the war’s nature is marked by shifting front lines and mixed populations, meaning that no group was solely a perpetrator or victim; all sides committed acts that contributed to the war’s devastating toll on civilians, and all sides led to massive displacement of populations. The graphic representation of Bosnia below underscores the intricate cohabitation of the three major ethnic groups, even 30 years after the war.

International involvement varied, with UN peacekeeping forces deployed but often criticized for their inability to prevent atrocities. NATO eventually launched airstrikes against Bosnian Serb positions, which, along with Croatian military successes, pushed the warring parties towards negotiation.

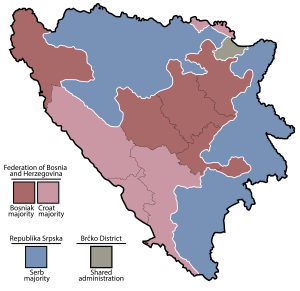

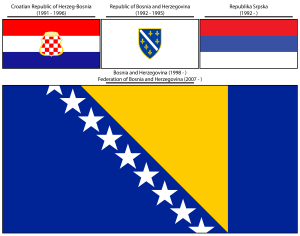

The General Framework Agreement for Peace, commonly referred to as the Dayton Agreement, signed in December 1995, officially ended the war. It marked the division of Bosnia and Herzegovina into two entities: the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (“Federacija” for short), and the Republika Srpska (“Republic of Bosnian Serbs”), linked by a central government. This setup, enforced by NATO-led peacekeepers and overseen by the international Office of the High Representative, aimed to maintain sovereignty while accommodating ethnic geographic divisions, while acting as a Constitution.

The war resulted in an estimated 100,000 deaths and displaced more than two million people, leaving an impact extending beyond its immediate aftermath. Children born in the diaspora learn at an early age about their parents’ experiences, maintaining a connection to a homeland they may have never visited. In Sarajevo, the legacy of the war is woven into the very fabric of the city, where “Sniper Alley” remains a used nickname for a street that was once a deadly gauntlet under the sights of snipers. The countryside is still marked by abandoned houses, pockmarked by bullet impacts. Even more, the Dayton Agreement is still enforced nowadays, and still acts as the country’s Constitution.

These elements collectively ensure the conflict’s memory persists.

Post-war Bosnia: political organization

Post-war Bosnia and Herzegovina operates under a complex political structure, designed with the goal to accommodate its diverse ethnic composition.

This structure is characterized by a form of confessionalism and federalism. Confessionalism is a form of government aiming for equitable representation and power-sharing among a country’s constituent groups. Embedded in the Dayton Agreement, it manifests in Bosnia as a rotating tripartite presidency, a number of parliamentary delegates proportional to each population group, a Constitutional Court divided between locals and foreign judges, and employment quotas within public institutions for the three main ethno-religious groups.

As mentioned, Bosnia is divided into two main entities: the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, predominantly Bosniak with an important minority of Croats, and the Republika Srpska, predominantly Serb. These entities are themselves subdivided into administrative regions, effectively making the Federacija a federal state within a federal state. Additionally, the Brcko District in the northeast acts as a neutral, self-governing administrative unit, which belongs to neither entity but is shared by both. This divisional system extends to cities like Mostar, which is administratively divided into Croat-controlled West Mostar and Bosniak-dominated East Mostar.

International oversight remains a critical aspect of Bosnia’s post-war governance, with the Office of the High Representative (OHR) overseeing the civilian implementation of the Dayton Agreement.

The High Representative has the authority to ensure compliance with the Agreement, which includes amending laws and removing officials who obstruct peace and democratic processes, effectively dominating Bosnia’s hierarchy of norms.

Current political landscape

The political orientation of Bosnia’s presidency and parliament is characterized by a spectrum of nationalism, from left to right leaning orientations, from pro-EU sentiments to independence aspirations.

The Presidency of Bosnia is collegial. The Serbian member of the presidency is elected solely by the voters of the Republika Srpska, while the Croatian and Bosniak voters in the Federacija vote either for a Croat candidate or for a Bosniak. The residents of the Brcko District, which belongs to neither entity, must register on the electoral lists of one or the other.

During the 2022 general elections in Bosnia, the Presidency elections resulted in Denis Becirovic (Social Democratic Party) being elected for the Bosniak seat, Željko Komšic (Democratic Front) being re-elected for the Croat seat, and Željka Cvijanovic (Alliance of Independent Social Democrats) taking the Serb seat, marking her as the first woman to serve in this role.

The Party of Democratic Action (SDA) remained the largest party in the House of Representatives with 9 seats, but was unable to form a government, leading to a coalition headed by Borjana Krišto (HDZ BiH) as Chairwoman of the Council of Ministers.

Recent elections have underscored the ethnic divisions of the country and the continued influence of nationalist parties, contributing to political stagnation. Efforts to reform the Constitution and electoral laws, aimed at more effective governance and EU accession requirements, have been met with limited success.

External powers, notably the European Union and Russia, play significant roles in Bosnia’s political dynamics. The EU has a tendency to maintain the current status quo, while promoting democratic reforms for integration. On the other hand, Russia has deep relations with Serbia and its neighbor the Republika Srpska, making an influential ally of Milorad Dodik, the current president of the entity who openly calls for independence.

Relations with neighbors like Serbia and Croatia are pivotal. While there are efforts towards reconciliation and cooperation, historical grievances and nationalist sentiments sometimes strain these relationships, influencing Bosnia’s internal politics and its path towards integration into European structures.

Municipal elections will be held in Bosnia on October 6th to elect mayors and assemblies in 143 municipalities. This election occurs amidst tensions, with increased risks of violence expected by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. Moreover, the wider Balkans region is gearing up for multiple elections, including presidential, parliamentary, and/or local elections in Croatia, Bosnia, Kosovo, North Macedonia, and Serbia, all of which will have an impact on Bosnia.

Ongoing challenges

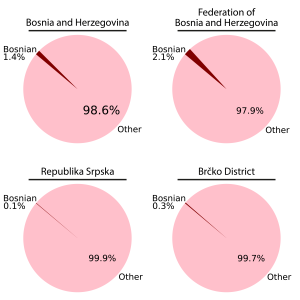

We have seen through this article the pervasive nature of nationalistic divisions within Bosnia. This context is further weakened by the near absence of a Bosnian national feeling, as we can see below from the Bosnian 2013 census:

In theory, this lack of a national sentiment would not be a problem if all the parties accepted the same terms and felt included equally within the political system.

However, within the Federacija, Croats have expressed concerns regarding their representation in both federal and local structures. Croats, a minority both within Bosnia and the Federacija, argue that electoral law amendments have skewed representation, resulting in Bosniak predominance in the upper house. This imbalance has sparked calls for a Croat-majority federal unit (or total independence for the most extreme positions), a proposal met with resistance from Bosniak parties. As mentioned above, the election of Croat members to the presidency can be influenced by Bosniak votes as they are part of the same federal entity, further raising tensions.

In the same note, the Republika Srpska has shown interest in increasing its autonomy or achieving independence from Bosnia and Herzegovina, with its political leadership, including Dodik. He is actively promoting these ideas and opposing the OHR’s decisions, viewing them as infringements on Republika Srpska’s autonomy. While a referendum for independence was proposed, it faced opposition both domestically and internationally, with warnings that such actions could destabilize the region. Serbia, sharing close ties with Republika Srpska, supports the entity’s interests. This support is balanced with Serbia’s broader international commitments, including its path toward European integration, with Serbia emphasizing the importance of respecting Bosnia and Herzegovina’s territorial integrity.

Reconciliation and cohabitation efforts in Bosnia are making strides but face ongoing challenges due to the country’s complex ethnic and political landscape. UNDP’s “Shared Futures” study, shows that young people show potential in fostering understanding and envisioning a shared future. However, for these efforts to effect lasting change, broader societal support and sustained engagement are essential.

Conclusion

Three major ethno-religious groups have populated Bosnia since its conquest by the Ottoman Empire. While those identities were controlled and restrained during the communist era in Yugoslavia, complex factors, including Tito’s death, led to a resurgence of divisions driven by nationalistic sentiments, which resulted in almost 4 years of war.

The Dayton Agreement, necessary to stop the bloodshed, has also introduced an immensely complex political infrastructure, incapable of reforming itself even after 30 years, resulting in widespread dissatisfaction among a large part of the population.

Exacerbated by tension and political actors, nationalistic sentiments, coupled with the lack of a strong Bosnian identity and with a feeling of misrepresentation from both Croats and Serbs, raise questions about the very existence of Bosnia and Herzegovina in the future.

In fact, since the end of the War, Bosnia faces the risk of disintegration. As we have seen, demands for increased autonomy have already been made and could escalate into secession. This scenario threatens not just Bosnia’s stability but also the entire region’s, potentially leading to a conflict if regional actors cannot reach any kind of agreement.

On the other hand, as Bosnia moves towards European integration, it would necessitate reforms enhancing democracy, rule of law, and economic standards. This process could usher in stability and prosperity, but also trigger counter-movements concerned with preserving national sovereignty and cultural identity, fearing loss of traditional values fueled by anti-Western propaganda.

No matter what path Bosnia will take, local and regional actors, as well as the international community, must ensure that dialogue is not broken between the different Bosnian stakeholders, in order to avoid regional destabilization and a potential new war. While figures like Dodik require close monitoring, the success of reconciliation, cohabitation, or even peaceful separation efforts all depends on the willingness of individuals and communities to engage in dialogue.

VISUALS CREDIT: Antoine Guignard Chevallier.

DATA SOURCE: Bosnia and Herzegovina 2013 census.

Note: Our analysis and visuals are based on the 2013 Bosnia and Herzegovina census. To clarify the data for our readers, we need to acknowledge three points: First, the census relies on individual and subjective statements, influencing the data represented in our graphics. Second, we focused on the three major ethnic groups in Bosnia and Herzegovina — Bosniaks, Serbs, and Croats — excluding individuals who identified their ethnicity directly through their religion (Muslims, Orthodox, Catholics). The census allowed this, and they represented a minority of respondents. Third, while we maintained clarity by limiting our focus, it’s important to recognize Bosnia’s greater diversity, which includes other minorities such as Romanis, Albanians, Turks, Ukrainians, Jews, or people still identifying as Yugoslavs.