Rifts have gradually started to appear in the Greek-Turkish rapprochement process since an informal moratorium on “provocative” actions in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean was formalised with the signing of a Declaration on Friendly Relations and Good-Neighbourliness by Greek PM, Mitsotakis, and President Erdogan in Athens in December 2023.

A Teetering Detente?

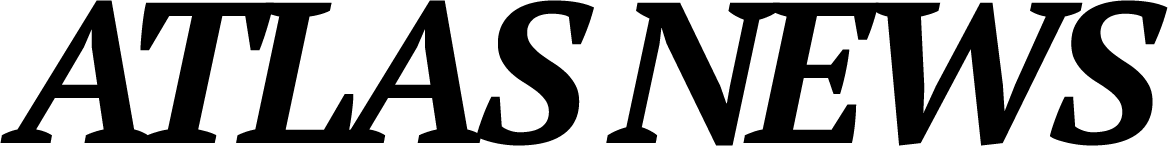

Greece’s introduction of two marine protected areas in the Ionian and Aegean seas, making it the first European state to announce a ban on the fishing practice of bottom trawling, has been met with stern warnings and announcements from Ankara. On April 9, Turkey’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a statement calling upon Greece “not to involve the outstanding Aegean issues, and the issues regarding the status of some islands, islets and rocks whose sovereignty has not been ceded to Greece by the international treaties, within the frame of its own agenda”.

Regarding the Marine Park to be Announced by Greece in the Aegean Sea https://t.co/Ldj7E4witR pic.twitter.com/cLBq4GDlxG

— Turkish MFA (@MFATurkiye) April 9, 2024

In the same tone, the Turkish Defense Ministry warned on April 18 that it “remains vigilant” over Greece’s plans to designate waters in the Aegean as protected marine parks.

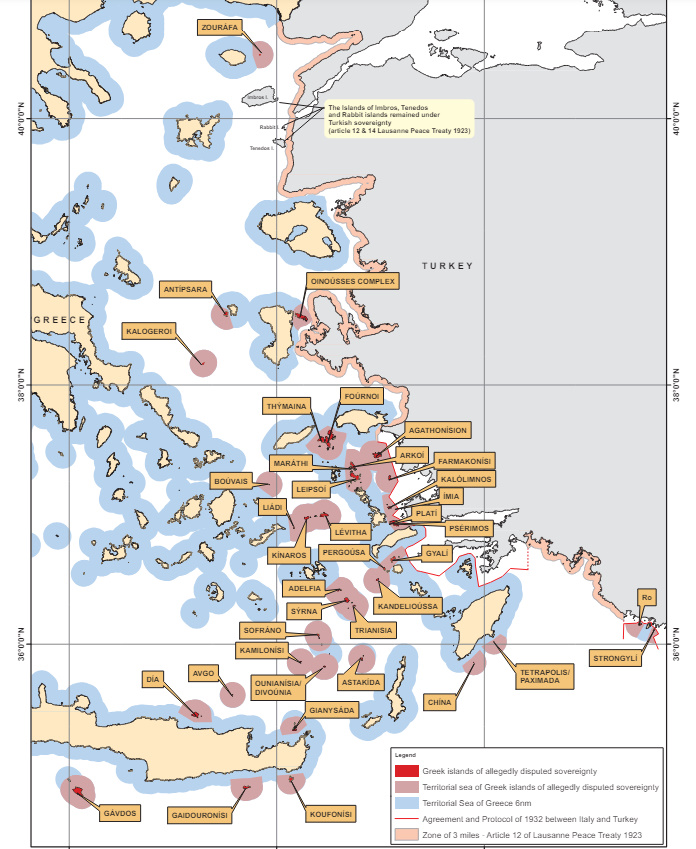

Ankara’s claims over the sovereignty of internationally recognised Greek islands are not new. In 1996 the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs introduced a novel claim, in an already growing body of unilateral contentions, that cast doubt over the Greek ownership of a large number of small islets and rocks in the Aegean. The Turkish rationale applied a novel unilateral interpretation of international law that disputed Greek sovereignty over the islets in a manner that no previous Turkish government had since 1973. It stipulated that islands not explicitly named in international treaties that determined Greek sovereignty over the Dodecanese and nearly all islands of the Eastern Aegean at 3 nautical miles off the Turkish coasts are of undetermined sovereign status.

This new addition to existing Turkish claims has since 1996 informed and shaped Turkish foreign policymaking and grand strategy vis-à-vis Greece in the Aegean. Dubbed by Greek academics, decision-makers and the media the “grey zones” theory, the Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs views this Turkish policy as a blatant attempt at revising the regional status quo in the Aegean Sea as set by the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne and the 1947 Paris Peace Treaty.

The dispute was constructed and forced into the Greek-Turkish conflict during the 1996 Imia crisis that saw the two NATO allies veer to the brink of all-out war as Greece sought to militarily deter Turkey from acting upon its then-newfound claims over the uninhabited Imia islets in the Eastern Aegean.

The crisis that was ultimately diffused with American mediation highlighted the consistently progressive nature of Turkey’s strategy that seeks to slowly but steadily erode Greek primacy in the Aegean through coercion and brinkmanship.

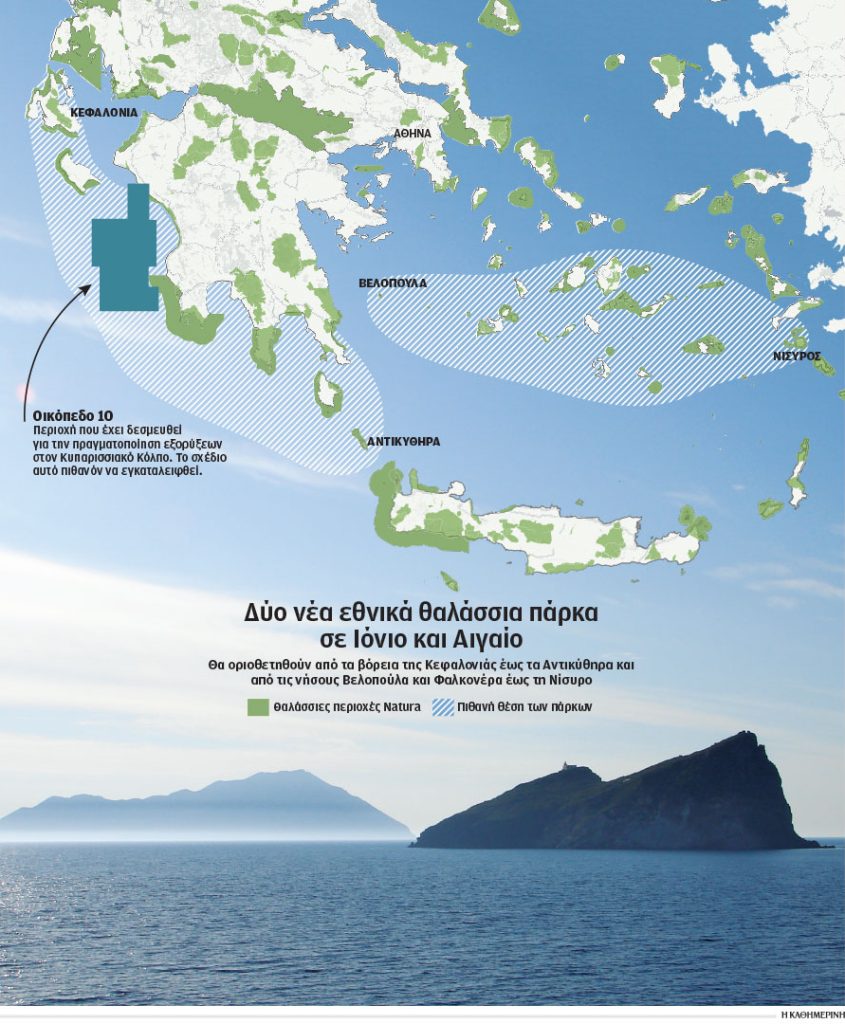

Turkey’s gradualist and dominant approach to setting and expanding the breadth and scope of the Aegean conflict and dispute becomes yet clearer when one juxtaposes an official Turkish map from 1969 suggesting that the Turkish state at the time did not regard the two Imia islets to be of ambiguous sovereignty to the contemporary scope of Turkish claims over Greek islets and rocks:

The Broader Context

Since Ankara first raised the issue of the delimitation of the Aegean continental in 1973, Athens has only recognised this matter as the sole bilateral dispute while the former has unilaterally introduced additional claims appertaining to the demilitarisation of Greek islands, the breadth of Greek territorial sea and airspace, the Athens Flight Information Region and Greece’s Search and Rescue Area (SAR) in the Aegean, among others.

This inherent complicacy in the overarching disagreement over the number and nature of bilateral disputes has been further compounded by Turkey’s rejection of the applicability of the United Nations Convention Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in negotiating the delimitation of the Aegean continental shelf.

In a period when Greek-Turkish tensions have been largely diffused ever since Greece embraced the path of “earthquake diplomacy”, reaching out with humanitarian aid and assistance in the aftermath of Turkey’s catastrophic earthquakes in February 2023, bilateral relations have appeared remarkably improved.

Turkish overflights and violations of the Greek national airspace and Flight Region Information (FIR) have been largely minimal to non-existent. Against this backdrop and following parliamentary and presidential elections in both countries in which incumbent Greek PM Mitsotakis and Turkish President Erdogan renewed their terms in power, a propitious moment was perceived to have arisen to reapproach the 50-year Aegean dispute anew. Both administrations have hence appeared encouraged to re-engage with one another and attempt to lay mutually agreed political parameters for redressing the dispute over delimiting the Aegean continental shelf in the International Court in the Hague. As admittedly the road to the Hague is long and tedious, diplomats across both coasts of the Aegean have simultaneously sought to tackle and foster more concrete cooperation on secondary issues of low politics, such as bilateral trade, immigration and confidence-building measures (CBMs).

The Dispute

The dispute over the delimitation of the Aegean continental shelf and the drawing out of respective Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) stands out as the longest-standing legal and political point of contention between the two neighbours. Dating back to 1973, the historical roots of the conflict lie in unilateral actions for the exploration and exploitation of undersea oil deposits in the Aegean that both sides have viewed as illegitimate and encroaching upon their claims for prospective EEZs.

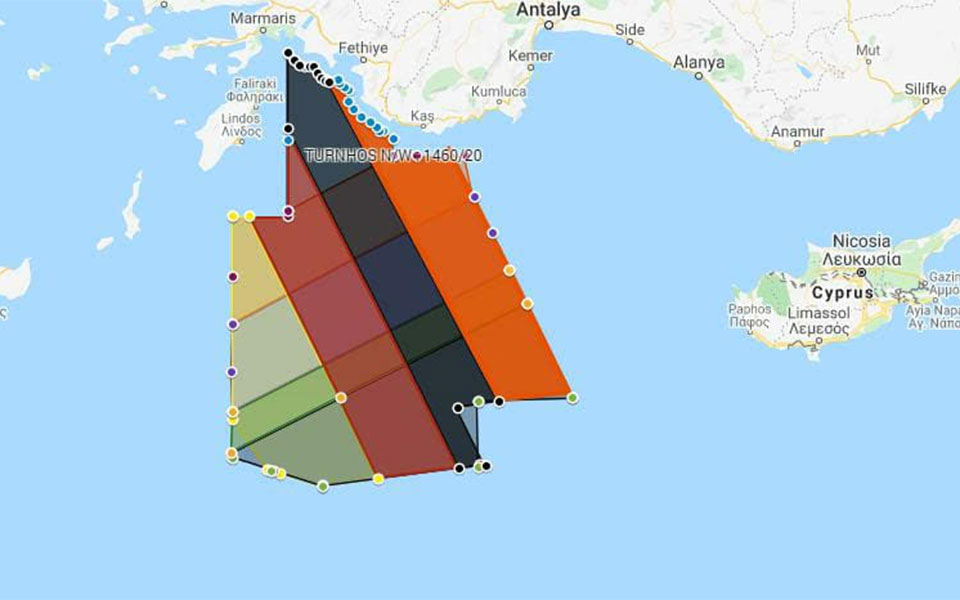

Military standoffs over Turkish exploration missions in the Aegean and East Mediterranean have drawn the two NATO allies to the brink of war on at least two notable occasions in 1987 and more recently in 2020, when the Oruc Reis seismic exploration and research vessel treaded into disputed waters southeast of Rhodes, accompanied by Turkish warships, provoking a counterbalancing military response from the Greek armed forces in defense of Greece’s claims in its prospective EEZ.

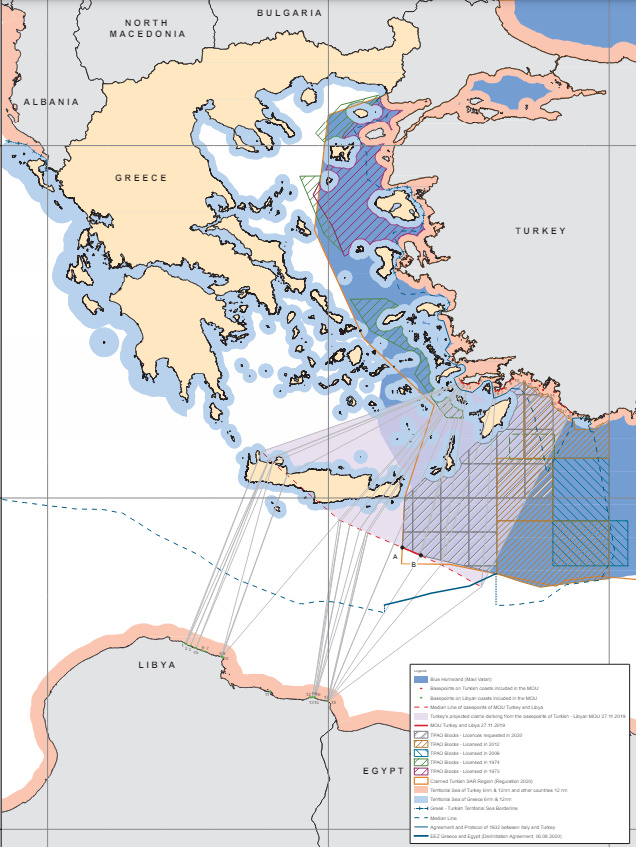

As of 2019 when Turkish claims were for the first time officially reiterated more holistically and coherently under the state-approved grand strategic doctrine of the so-called Blue Homeland (“Mavi Vatan”), the following map captures their full contemporary scope and breadth vis-a-vis Greek territory and EEZ claims.

As shown on the map, the total sum of Turkish claims that make up the so-called “Blue Homeland” seeks to extend the state’s maritime jurisdiction up to the 25th meridian that traverses and effectively cuts the Aegean Sea in half. Greece’s lack of continental strategic depth and its 227 inhabited lands that span across the Aegean have made a bargain with Turkey over maritime delimitation hard to come by.

The growing plethora of additional claims ranging from the grey zones theory to the 1995 casus belli declaration by Turkey’s Grand National Assembly on a potential expansion of the Greek territorial sea from 6 to 12 nautical miles (n.m), as afforded by UNCLOS, have made the Aegean conflict an existential issue to the sovereign territorial integrity of the Greek state. Turkey’s linkage of a long-standing on the partial demilitarisation of Greece’s Eastern Aegean islands to a novel contention in 2022 that Greek sovereignty is conditional upon their demilitarisation certainly did little to mitigate existential security concerns.

On the other hand, Turkish fears over the Aegean becoming a “Greek lake” if Greece is to expand its territorial waters to 12 n.m. reflect its concerns over greater Greek relative gains. About 70% of the Aegean’s waters would fall within Greek territorial sea, while Turkey’s would only increase at about 10%.

The country’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has officially articulated its position in the following manner:

“The impact of such a Greek extension of its territorial waters would be to deprive Türkiye, one of the two coastal states of the Aegean, from her basic right of access to high seas from her territorial waters, the economic benefits derived from the Aegean, scientific research, etc.”

To Be Continued in Part II…