On May 15th, YouTube blocked 32 videos of the song Glory to Hong Kong after Hong Kong’s (HK) High Court overturned a previous verdict. The High Court rejected the government’s initial bid in a July 2023 ruling that cited “free speech concerns,” specifically its chilling effect. However, the ruling allowed the government to appeal the verdict in the future.

Glory to Hong Kong and 2019 Protests

Glory to Hong Kong was written by a Hong Kong-based songwriter named “Thomas” and a team using lyrics co-written by people from the forum LIHKG. The writer incorporated the illegal phrase “liberate Hong Kong; revolution of our times” after he received feedback from the forum posters. Thomas and the group released the song on YouTube and other streaming services, such as Spotify, in August 2019 during the pro-democracy protests. The song became very popular among the protesters and pro-democracy politicians during the protests, with protesters singing the song at several demonstrations.

The 2019 protests were in response to the HK government’s plan to amend the Fugitive Offenders Ordinance to allow HK citizens to be extradited to mainland China for trial. The protesters’ concern was that the Chinese government would use the law to slowly break down the ‘one country, two systems’ enacted after the United Kingdom handed the city back to China in 1997.

Efforts to Ban the Song

In the aftermath of the 2019 protests, the government moved to restrict the song through various means because of its association with the protests. The government also wanted to prevent people from mistaking the song for the city’s national anthem. In July 2020, the government banned the song, claiming it promoted independence and separation from mainland China due to its inclusion of the phrase in the song. The government stated that individuals who used the slogan in any capacity would face persecution under the city’s National Security Law (NSL). In July 2021, the city’s High Court sentenced an activist to a nine-year sentence for carrying a flag with the saying on it during the protests.

The city renewed efforts to ban the song after it was accidentally played instead of Hong Kong’s national anthem, March of the Volunteers, during the 2022 Asia Rugby Sevens game. The accident occurred before the Hong Kong team played a match during the South Korea leg of the series in November 2022. The government called for Asia Rugby to launch an investigation to determine why Glory to Hong Kong was played instead of March of the Volunteers. The investigation determined that an intern “reportedly downloaded” the song from the Internet, believing it was the real anthem for Hong Kong. Furthermore, the intern also downloaded the song because it showed up as the top song instead of March of the Volunteers. In late November 2022, the government demanded that Google remove Glory to Hong Kong from its internet search results and other platforms, such as YouTube. The government also issued similar demands to other Internet providers to remove the song from their platforms. However, Google and other providers either ignored the request or said that the government needed a court order.

The city renewed efforts to ban the song after several incidents occurred when Glory to Hong Kong was played instead of China’s anthem. The first incident happened in November 2022, when the song was accidentally played instead of Hong Kong’s national anthem, March of the Volunteers, during the 2022 Asia Rugby Sevens game. The government called for Asia Rugby to launch an investigation to determine why Glory to Hong Kong was played instead of March of the Volunteers. The investigation determined that an intern “reportedly downloaded” the song from the Internet, believing it was the real anthem for Hong Kong. Furthermore, the intern also downloaded the song because it showed up as the top song instead of March of the Volunteers.

In late November 2022, the government demanded that Google remove Glory to Hong Kong from its internet search results and other platforms, such as YouTube. The government also issued similar demands to other Internet providers to remove the song from their platforms. However, Google and other providers either ignored the request or said that the government needed a court order. Another incident occurred in March 2023 when the song was played at an ice hockey game between Iran and Hong Kong for the World Championship Division III Group B match in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The government issued a statement in which it expressed strong dissatisfaction and requested that the local Olympic committee investigate.

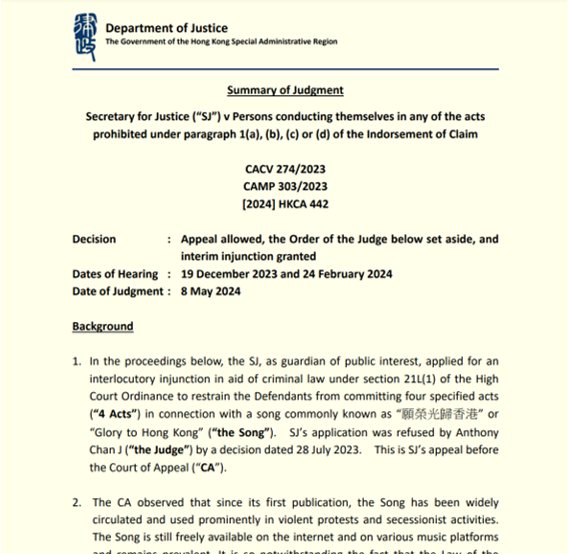

In July 2023, the city’s High Court rejected the government’s initial bid to ban the song over concerns the order would have a ‘chilling’ effect on freedom of speech. The judge that presided over the hearing, Judge Anthony Chan, said that he was not satisfied that “it was ‘just and convenient’ to grant the government’s request for an injunction.” He also pointed out that the injunction “was aimed at criminal acts but not lawful activities.” Chan believes “that the intrusion into freedom of expression here, especially to innocent third parties, is what is referred to in public law as chilling effects.” Chan then said that he is unable to “agree that the chilling effects may be dismissed simply because the Injunction is not aimed at lawful pursuits.”

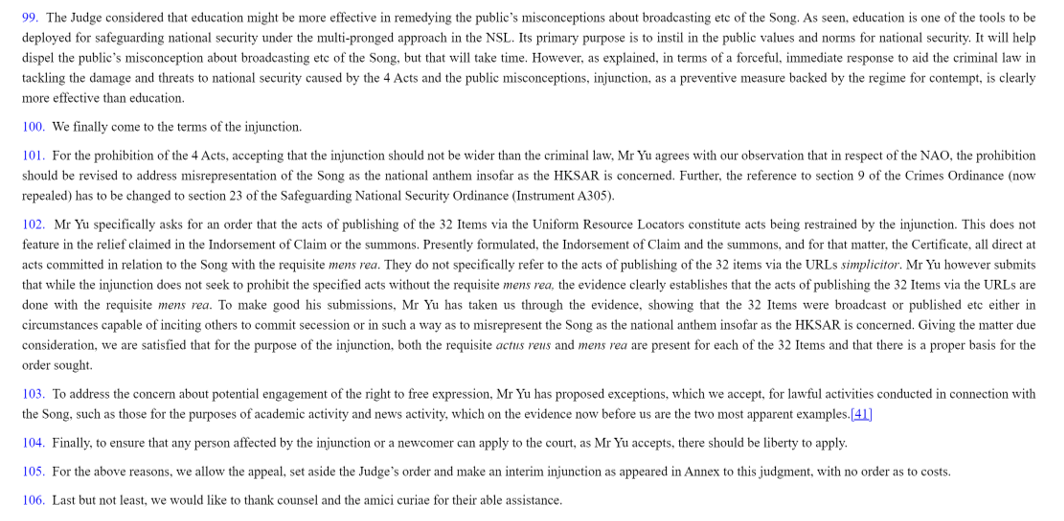

However, the Hong Kong Court of Appeals reversed the High Court’s decision on May 8th, saying that the injunction the government sought was required to persuade Internet providers and platforms to block or remove 32 videos it deemed “problematic.” The three judges said their decision was based on the Internet providers saying that they would comply with the city’s request if there was a court order. They also based their decision on the impracticability of bringing proceedings against each of the providers. Furthermore, the judges said a “more effective way to safeguard national security in such circumstances” is to ask the providers to stop assisting the acts.

On May 13th, Secretary of Justice Paul Lam said the government informed Google of the injunction order and was “anxious” to see Google’s response since they previously wanted a court order. Lam commented after the appeals court overturned the previous ruling that the government would ask Internet service providers to comply with the injunction order. He referenced how providers such as Google had previously asked under what circumstances or red lines the song would be considered seditious. Lam said that the court order now clearly defines using the song, Glory to Hong Kong, with the intention of sedition as illegal.

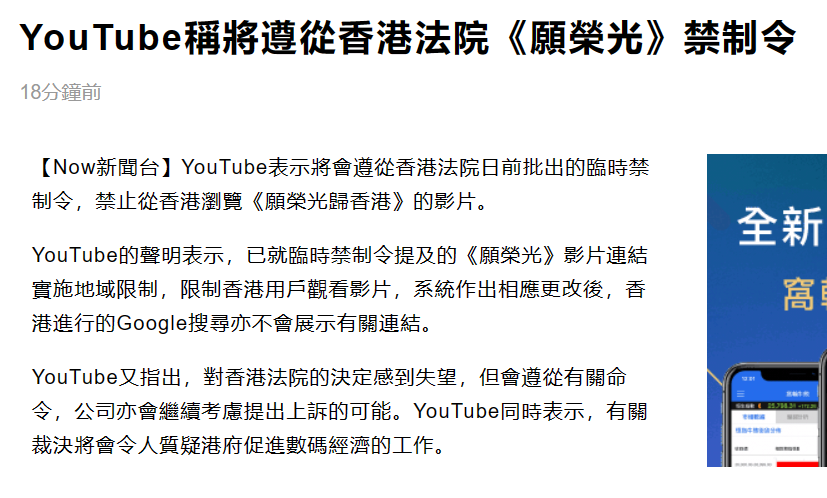

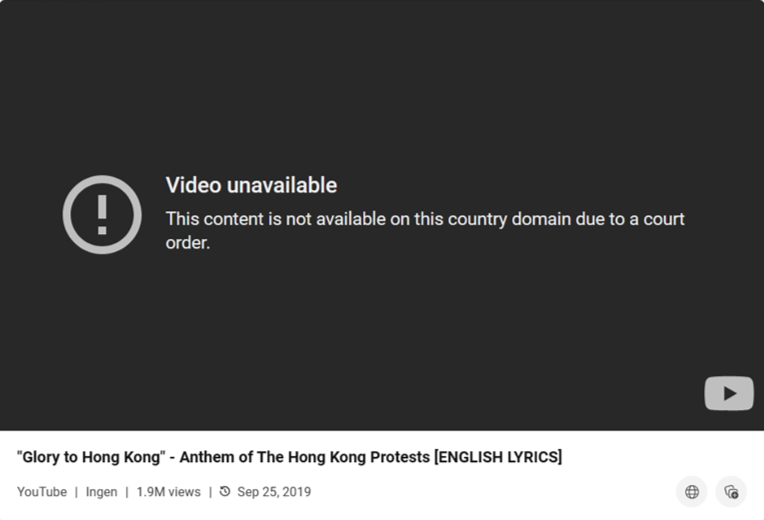

Furthermore, he said that the court has now outlined the red line, and all Hong Kongers and all Chinese eagerly expect Google to respond to the request. YouTube complied and blocked the 32 videos outlined in the ruling from being viewed by Hong Kong users on May 15th Hong Kongers who attempt to access the listed videos will now see “This content is not available on this country domain due to a court order.” However, users can still access other versions of the song on YouTube and other platforms, such as Spotify.

Analysis

The court’s ruling to issue the order to ban the 32 videos on YouTube represents a continuation of Hong Kong’s efforts to eliminate any independence movements. Furthermore, the ruling also represents the government’s willingness to use the judiciary to prevent the circulation of any subversive information. The order is the government’s latest measure to prevent the circulation of the song and other subversive material in the city. For example, the government tried people under the National Anthem Ordinance enacted in June 2020, with the first trial occurring in July 2023. The trial resulted in the individual receiving a three-month sentence for replacing Hong Kong’s national anthem with Glory to Hong Kong in a video that showed a Hong Kong fencer receiving a gold medal in the 2021 Olympics. However, the city faced limitations in applying the ordinance, the NSL, and other similar laws designed to stifle and prevent the development of democracy and independence movements.

This limitation was most notable when authorities were unable to force companies such as Google to remove or prevent the song from being disseminated or viewed in the city. The providers argued that they could not remove the videos because it would violate their guidelines on removing harmful content. Furthermore, the companies also argued that they would need a court order to comply with any request or demand regarding the removal of the videos. The companies’ rationale for using this argument is that they do not comply with Hong Kong’s requests. Furthermore, they understood that removing the videos would create a precedent that Hong Kong could use in the future to force them to ban other material the city considered subversive.

The government decided to use the judiciary to force Google and other companies to remove the content since it was their only avenue to do so. However, Hong Kong faces some obstacles in getting its injunction approved by the city’s courts. The first ruling that rejected the government’s petition indicates that some in the judiciary understood the chilling effect that any order to remove the videos would have on free speech. However, the judge allowed the government to appeal its decision in the future. The approval shows that the judiciary will approve petitions and other legal actions the government brings forward if they are based on national security concerns, as outlined in the NSL. The courts will limit the scope of what material would be considered subversive under the law to balance between free speech and national security concerns.