The Colombian conflict is an ongoing 60-year internal conflict between various politically-motivated armed groups and government forces. The conflict has killed nearly half a million people while 120,000 more reportedly disappeared during the fighting.

The Spark of the Conflict

The conflict can trace its history back to a bloody period of Colombia’s history known as “La Violencia.” This period commenced with the assassination of Jorge Eliécer Gaitan in 1948, an attorney, prominent figure, and presidential hopeful who’s main supporters consisted of the working class of Colombia. Gaitan’s death served as a catalyst, plunging the nation into a maelstrom of violence characterized by a multifaceted conflict between conservatives, liberals, and communist factions.

While Gaitan was working at his office, the lawyer was approached by one of his supporters for lunch. Gaitan accepted and was soon joined by a number of other supporters. Once the lunch concluded and the party was leaving, a gunman by the name of Juan Roa Sierra appeared in front of Gaitan, shooting him several times before fleeing the scene.

Following his death, a mob of enraged bystanders chased Roa across the city with the intent to kill the assassin. Roa eventually encountered a police officer and pleaded for his life. The officer reacted quickly, dragging Roa into a nearby drug store before locking the door behind him. This attempt to save Roa’s life failed, as the angry mob broke into the building and dragged the assassin from the grip of the police.

What followed was a brutal case of mob justice and Roa’s death by beating, the mob parading his body to Bolivar Square which houses a number of congressional buildings, most notably, the Presidential Palace. Gaitan’s supporters quickly blamed the conservative elements of Colombian society, claiming that the government of then-president, Ospina Perez, had orchestrated the killing.

Further rioters were influenced to join the melee by a radio station which broadcasted the news of Gaitan’s death before calling the general populace to action. This led a number of civilians living in Bogota to converge on the city’s downtown, looting stores, arming themselves with pistols and machetes, and even looting the police station in the process. The Conservative and Liberal political parties of the country would plead to the rioters to end the period of violence in the city but to no avail. Soon after the riots in Bogota, similar acts of public disobedience would break out across the country.

Seeing that pleas would be no help in quelling the riot, authorities began an offensive against those participating in the civil strife.

When the riots were quelled, an estimated 3,000 people were left dead while 570 million dollars worth of damage was recorded across the country. The damage to property was indiscriminate, with both public buildings such as the Ministry of Education being ransacked alongside private buildings in downtown Bogota. An estimated 157 buildings in downtown Bogota had suffered serious damage, while 103 of those were declared a total loss according to Herbert Braun, a professor at the University of Virginia who documented the losses in his book: “The Assassination of Gaitan: Public Life and Urban Violence in Colombia.”

To this day Gaitan’s killing remains under debate, some believing that the conservative government had the budding politician killed as he threatened the conservatives’ political power. Others have suggested the assassination was conducted by the CIA due to Gaitan threatening American interests in the nation due to his desire to redistribute wealth across the country alongside his nationalistic tendencies.

Disputes regarding the death of Gaitan are not limited to the killer, however, as some even debate when and how the lawyer was murdered. While many believe that he was killed at lunch with colleagues, others claim Gaitan was shot while leaving his office by none other than a police officer. There also remains claims that the lynched man was not actually Gaitan’s assassin, with some eyewitnesses to the confrontation with the police officer stating that the officer grabbed the wrong man from the crowd.

Ultimately, the damage was done. Bogota was left in ruins following the infamous riot, now known as “the Bogotazo,” and the times were only beginning to get rough.

La Violencia

After the Bogotazo, a brutal civil war erupted within Colombia’s countryside between left- and right-wing factions. During the conflict, leftist guerillas would ambush government forces while right wing paramilitary groups with the complicity of public officials seized the land of those who they deemed communist supporters.

These attacks would lead to the deaths of hundreds of thousands, and displace millions of peasants from the countryside who would flee to the urban cities of Colombia. Their relocation would lead to the formation of communist popular brigades in the cities, and would help form future guerilla groups such as the National Liberation Army (ELN).

In the early days of La Violencia, both liberals and conservatives worked together in order to quell the simmering violence within Colombia. This relationship would eventually die out in 1949 politicians belonging to the liberal party and partaking in President Perez’s administration resigned from their position, citing the crackdown on liberal ideals by authorities.

But hope was not lost for the liberals. After their resignation, the liberals who held a majority in Congress began impeachment proceedings in order to bring an end to both President Perez’s reign and the growing violence. This attempt ultimately fell flat, as Perez dissolved Congress and instituted a number of bans against public gatherings, enacted what has been considered “censorship” policies, and declared a state of emergency amid La Violencia to ensure the conservatives’ grip on power. These policies succeeded, as Perez’s conservative successor easily won the presidential election in 1950 after a mass boycott by the liberals.

This successor was Laureano Gomez, a conservative party figure considered to be radical even for the period of La Violencia. However, midway through his presidency Gomez was forced to cede the presidential office after suffering a heart attack in 1951 which left him partially paralyzed. In his stead, he appointed Roberto Urdaneta Arbeláez as interim president.

During his time as president, Gomez pushed hard to reform the Constitution of Colombia in order to grant further power to the executive branch and the upper class. This push would culminate in the formation of a National Constitutional Assembly in 1952 to do just that. The reform would pass largely due to both the liberals and a dissident faction within the conservative party boycotting the vote, the reforms were set to take effect in 1953 but a sudden shift in power prevented the document from ever being implemented.

This faction of the conservative party would be known as the Ospinists who were supporters of the former president and more moderate in their beliefs than those supporting Gomez. Gomez had angered a number of liberals, and by doing so had sowed distrust with his fellow conservatives. The moderates sought to bring an end to the years of civil infighting that came with La Violencia, and a plan was hatched to depose Gomez.

Gomez would attempt to return to office in 1953 prior to the reforms coming into effect. Upon his return, the president learned of the promotion of Gustavo Rojas Pinilla to the Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces of Colombia by Arbeláez. Gomez would demand that Rojas be removed from his position due to the soldier’s threat to Gomez’s power, a demand that would not be taken lightly by the Chief and his supporters.

Prior to his promotion, Rojas was a colonel stationed in Cali, the capital of Colombia’s Cauca department. It was during this time that Rojas would first make a name for himself after he successfully negotiated with rioters in Cali as a byproduct of the Bogotazo. It was likely due to these actions that Rojas would then be promoted to Lieutenant General and became a key player in the conservative party’s factionalism.

After this demand, former president Ospina knew it was time to depose Gomez. Ospina told Rojas to rally a military battalion to march on the Presidential Palace in Bogota. The march faced no resistance, and Gomez would flee with his family to New York and later Spain ahead of the coup. The absence of Gomez led Ospina to request Arbeláez take the presidential office. Arbeláez refused, stating that he would only take power if Gomez officially resigned. This statement took the coup plotters by surprise, and discussions were launched in order to decide who would be the next president.

These discussions were cut short by Colombia’s Minister of War, Lucio Pabon Núñez, who had previously refused to remove Rojas from his position. Pabon told Rojas that he must become president in order to prevent the total destruction of order within Colombia. Following an endorsement by Ospina and Arbelaez, Rojas was reluctantly promoted to the position.

Rojas began a number of reforms within Colombia following his ascension to power, first promising to cut down on the censorship of the media and granting amnesty to a number of liberals and armed insurgents fighting against government forces. These moves successfully earned him trust from those who had historically been opposed to the conservatives and led to a number of armed fighters surrendering to government forces. Next, he allowed women to vote, founded television channels, built hospitals and universities, and formed a new labor union which gave workers an alternative to the conservative and liberal held unions.

He also funded a number of infrastructure projects, building roads, railways, and a hydroelectric dam. However, in order to fund these projects Rojas increased taxes on the wealthy and businesses in Colombia, angering a portion of the conservative party. This growing opposition would lead the president to shut down his newly formed union.

However Rojas fell short of key promises to appease the liberal elements within Colombia. He maintained censorship of the press, and the television and radio stations he had founded were largely used to spread pro-government propaganda which led to further friction with the liberals. Rojas further made it more difficult to purchase and own a firearm, leading some to worry that the president had authoritarian motivations.

Two more situations would eventually culminate in Rojas’ resignation. First, the Colombian economy began to falter after the price of coffee, a key export for Colombia even today, began to drop. This led to an economic crisis within the country and forced the government to take on a large sum of debt to the International Monetary Fund. Finally, Rojas’ grip on power would fully slip after the president announced he would serve for another term in office. This would lead the Liberal Party’s leader, Alberto Lleras Camargo, to meet with the exiled Gomez who was residing in Spain at the time.

The two would sign the Pact of Benidorm, a plan for both the conservatives and the liberals to stand against Rojas’s planned candidacy. When the time finally came and Rojas announced his candidacy, the Liberal Party called for a mass strike against the incumbent, and days later, in 1957, Rojas ceded power to a military junta.

The junta held power until the following year when Alberto Lleras Camargo, a journalist and liberal party politician, won the presidential election and the National Front was established, effectively ending the era of La Violencia. The National Front was a coalition government between liberals and conservatives which saw the presidential office transferred from one party to the other for four presidential terms, while also ensuring equal representation for both parties on all executive and legislative bodies and limiting the power of third party political movements. Yet, despite these efforts, tensions between leftist and conservative factions continued to simmer beneath the surface.

A Conflict After a Conflict

What came after La Violencia was what is known as the Colombian Conflict, a war between leftist guerilla groups, right-wing paramilitaries, criminal organizations, and government authorities. This conflict, which continues today, has stolen the lives of hundreds of thousands of people and has been the source of a great deal of controversy both for Colombia and foreign nations such as the United States.

The FARC

The Communist Party of Colombia emerged as a formidable player in post-La Violencia Colombia, leading the formation of “self-defense communities” comprising rural peasants and urban workers. These communities acted as strongholds of leftist resistance, organizing strikes, asserting land rights, and defending against incursions by government forces and right-wing paramilitaries.

It was during this era of upheaval that the seeds for the formation of the leftist guerilla group known as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC)–a group still active in Colombia today–were sown. The group’s origins trace back to an attack in 1964, where 48 armed FARC defenders stood against 16,000 Colombian troops. Despite being outnumbered and outgunned, the survivors regrouped and retreated to safety in nearby mountains where the early form of the FARC took shape.

Originally envisioned as a group dedicated to bringing class revolution to Colombia, the FARC would begin its operations by targeting military convoys and other targets of strategic importance to the Colombian government. The group’s numbers would quickly swell as they carried on their attacks, but the FARC remained limited to small-scale guerrilla encounters with government forces.

This would change following what is commonly known as the “Coca Boom,” a period in which the production of coca, the key ingredient to the production of cocaine, would increase exponentially, expanding the groups’ coffers with more funds for operations. This allowed the FARC to bring in more guerillas, offer proper training, and obtain better weapons for their war against the government.

With the increased funding, the FARC would transform into a true rebel power, and at a FARC leadership meeting now known as the “Seventh Guerrilla Conference” in 1982, the group would expand their operations to urban areas of Colombia, while sending promising soldiers to the Soviet Union and Vietnam for professional training.

The FARC’s stronghold was located in Colombia’s “green belt,” a region famous for its abundance of emerald deposits. These precious green jewels would give the FARC even more financial power alongside their control of the coca fields.

However, this wouldn’t be enough for the guerilla group, and soon the FARC began to enact “taxes” on civilians living in their territory, before further expanding their operations into the cocaine trade to the United States.

As time passed, dialogue would open up between the FARC and the Colombian government with a multitude of peace talks being organized by both sides. Talks ranged from negotiations in 1990 to the group’s eventual official ceasefire in 2016 under the presidency of Juan Manuel Santos. The momentous ceasefire saw the bulk of the FARC disarmed and disbanded. Despite the ceasefire, however, a number of remaining, hardline members of the FARC and those who did not wish to forfeit their exclusive and profitable careers continued their operations against the government and the people of Colombia. These groups would label themselves as “fronts,” a leftover from the group’s original structure, and break into two factions.

The first, the FARC-EMC, would be founded by one of Colombia’s most wanted criminals, Miguel Botache Santillana, going by an alias Gentil Duarte, who was a main negotiator during the peace conference between the FARC and the Colombian government held in Cuba. After negotiations failed, Duarte returned to Colombia and attempted to unite FARC’s other fronts into one body and continue the organization’s armed struggle against the government. This would succeed, and in 2017, Duarte and another commander, Ivan Mordisco, would announce the birth of the united FARC-EMC.

Their main rival would prove to be the Second Marquetalia, which was formed by a number of former FARC commanders, many of whom previously accepted the ceasefire but would rearm in 2019. The group’s main territory encompasses the Venezuelan-Colombian border, where the FARC has historically enjoyed a great deal of protection from authorities in Venezuela. The Second Marquetalia would even come into conflict with another dissident faction of the FARC. This faction, known as the 10th Front, had refused to support the leaders of the Second Marquetalia, who had attempted to pull rank on the dissidents in Venezuela following their rearmament. Following the refusal, the 10th Front would face direct action by Venezuela’s military, in what Insight Crime reports was an attempt to grant further power to the Second Marquetalia.

The ELN

The National Liberation Army (ELN) was founded in 1964 by a group of Colombian communist rebels who were formally trained in Cuba. The group would later be led by Catholic priests who practiced Liberation Theology, a belief system focused on addressing wealth inequality within Catholic teaching and through the clergy. A number of similar theological methods would also be adopted by Catholic priests in nations spanning from the United States to South Africa and even South Korea.

The key difference between the ELN and the FARC is the background of the members. While the FARC was composed largely of rural peasants and farmers, the ELN comprised a number of leftist students and academics who sought to change life within the urban centers of Colombia.

The ELN would finance their operations through the taxation of the drug trade, extortion of Colombian civilians, kidnap-for-ransom schemes, and eliciting protection payments from corporations in exchange for not attacking their operations.

The first real peace talks with the ELN would begin in 2002, when the Colombian government would approach the group and eventually agree to meet in Mexico to conduct peace negotiations. The discussions would be moved to Cuba following a falling out between the ELN and the Mexican government before negotiations could begin. This negotiation attempt would eventually fail in 2007 due to disagreements regarding the conditions of the agreement.

The ELN also historically operated in Venezuela for decades; these operations only increased following the disarmament and disbanding of the FARC in 2016. Following the FARC’s disbandment, the ELN and another criminal group, Clan del Golfo, quickly began to occupy the newly vacant territory, leading to a number of clashes between these groups and government forces.

Talks would eventually be restored, but with no permanent ceasefire; however, a number of temporary ceasefires would be negotiated throughout the years. One such ceasefire was negotiated in 2021 but fell apart by the next year with the election of Colombia’s first leftist president, Gustavo Petro.

Petro worked to establish peace talks with the ELN throughout the early years of his presidency; the ELN was initially receptive until April 2024, when the armed group formally announced they would take a step back from negotiations.

This bombshell declaration followed a slow deterioration of relations between the ELN and the Colombian government that began in February 2024. The ELN accused the Colombian government of pursuing the disarmament and disbandment of the organization’s Nariño front, stating that dual negotiations were not viable for peace talks.

The ELN claims this front is in reality a part of the government’s plan to target the group’s command structure in one of the group’s publications, Insurreccion 947. The group claims that the peace talks with the Narino front have only matured due to the supposed government agent’s failure to target core leadership of the ELN.

Furthermore, the publication states that this issue was brought up by the organization’s official negotiators at meetings with the Colombian government but were ultimately ignored resulting in the ELN leaving the talks.

“Now, activating the supposed ‘dissidence,’ the government has given priority to said setup, relegating the official Roundtable with the ELN and therefore confirming that its priority is to hold peace dialogue with its own intelligence agents,” the publication stated.

The AUC and Clan del Golfo

During La Violencia and the following years of conflict, various right wing paramilitary groups formed to combat the rise in communist ideology, many of them being funded by both the government and drug lords seeking to protect their profits from rivals.

These groups were originally founded in 1962 after the US government sent counterinsurgency experts to Colombia to aid the government in restoring order and rooting out rebels within the country. Authorities trained civilians on how to combat the rebel threat, its original purpose to protect private landowners and government officials.

But these new paramilitaries would undergo a change following the explosion of the cocaine industry and the subsequent rise of wealthy drug lords. These drug lords abused the law which allowed landowners to form paramilitaries in order to protect the production of cocaine as well as prevent the communist guerillas from redistributing the land which was used for the cultivation of coca leaves.

These communist guerrillas’ largest foe would be the United Self Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC). The AUC would prove to be the largest paramilitary group in Colombia and was the result of a merger of the majority of right wing paramilitary groups.

The AUC draws their origins back to some of the first paramilitary groups in Colombia, most notably the Peasant Self-Defense Forces of Córdoba and Uraba (ACCU). The ACCU was founded in Córdoba by three brothers, Fidel Castano, Carlos Castano, and Vicente Castano after their father, a wealthy landowner and right wing supporter, was kidnapped and killed by the FARC.

The brothers would make a fortune through smuggling illegally-mined emeralds, weapons, and narcotics under the organizational structure of Pablo Escobar’s Medellín Cartel. The group would also profit from the sale of information about alleged communist guerillas to government death squads. The brothers expanded their influence across the region with Fidel hiring a group known as Los Tangueros sometime in the 1980s to fight against a local communist guerilla group known as the Popular Liberation Army.

The group wouldn’t last long, and Fidel would officially disband the group after the Popular Army agreed to lay down their arms and return to normal life. However, with the group’s absence the FARC occupied their former territory, effectively undoing the work Fidel had done in the region.

While Fidel was fighting in Colombia, Carlos underwent anti-guerilla training in Israel in preparation for the fight against the communists. He became enraged when he returned and saw his brother had disbanded the organization. Carlos would go on to revive the group and strike back at the FARC, while working alongside government forces, brutally executing anyone thought to be associating with the communists. The group quickly expanded, taking control of vast swathes of territory in northern Colombia, a key route for drug trafficking. The group would eventually become more involved in the smuggling of cocaine and other narcotics to the United States through the Caribbean, a business venture Carlos would come to despise due to his hatred of drugs.

In 1994, however, a leadership change would shake up the ACCU. Fidel was killed in a communist ambush. Officially, the ACCU claimed that Fidel and his bodyguards were killed by dissident Popular Army members who rejected the group’s disarmament.

Others claimed that Carlos orchestrated the assassination after his brother allegedly murdered a woman the two both shared a romantic relationship with. Another theory suggests it was due to Fidel’s alleged involvement in the killing of his own sister, Rumalda Castaño.

Regardless, Fidel would go missing and was presumed to be dead by much of the ACCU, with authorities recovering what is believed to be his body in 2013.

Three years after his brother’s death, Carlos saw the ACCU evolve into the AUC, a merger of the majority of right-wing paramilitary groups in Colombia. While some groups would refuse the merger, the AUC would still become Colombia’s largest right-wing paramilitary group with its hands in everything from narco-trafficking to illegal mining. Aside from the government, this new paramilitary group would prove to be the FARC’s greatest opponent, effectively keeping the communist militia out of northern Colombia.

The AUC officially continued operations until 2003, when the government offered a peace deal to the group. The deal originally allowed disarmed members to keep their illegally-procured assets and avoid prison, serving what little time they were sentenced on lucrative private farms. Those terms continued through 2006, when the Colombian government refined the terms of the peace deal to appease widespread demands that punitive action be taken against those wishing to disarm for their previous crimes and activity.

However, a large number of members refused to lay down their arms and accept the terms, leading to the AUC’s collapse into dozens of splinter groups. The most noteworthy offshoot was Clan del Golfo, a narco-terrorist organization active in the AUC’s old territory in northern Colombia. This newly born group would be led by Vincente Castano and under his leadership the group would continue many of the AUC’s methods to raise funds, including extortion, kidnapping for ransom, and, most importantly, producing and trafficking cocaine.

Clan del Golfo would go on to dominate the cocaine trade after conquering rival criminal and splinter groups from the dissolution of the AUC, quickly becoming one of Colombia’s most notorious criminal groups with the government dedicating large-scale military operations in an effort to bring them down.

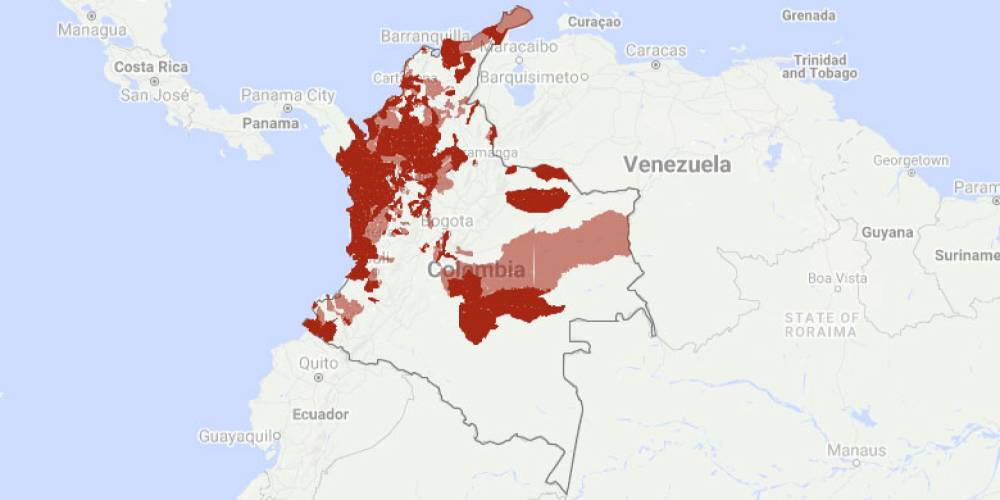

Clan del Golfo currently controls a vital smuggling route into the United States. With their control of northern and western Colombia and its coast line, the group can easily smuggle cocaine and other contraband through the Caribbean directly into the US or into eastern Mexico for the various cartels to smuggle across the southern border.

In recent years, Clan del Golfo has been somewhat reduced following the arrest of their leader, Dairo Antonio Usuga David, also known as “Otoniel,” in October 2021 by Colombian military and law enforcement forces. Following his arrest, Chiquito Malo, a key lieutenant in the organization, took charge of Clan del Golfo.