Introduction

There are many regions of the world that have fallen out of the mainstream spotlight. Areas in which there is no shortage of human suffering, however, they remain hidden from the eyes of the world. Sadly, this problem has only increased with the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the Israel-Gaza war, both of which have captured the attention of the world.

As these wars rage and take innocent lives, similar atrocities are ongoing in virtually every corner of the globe. One such region which has failed to capture global attention is the northern Ethiopian region of Tigray.

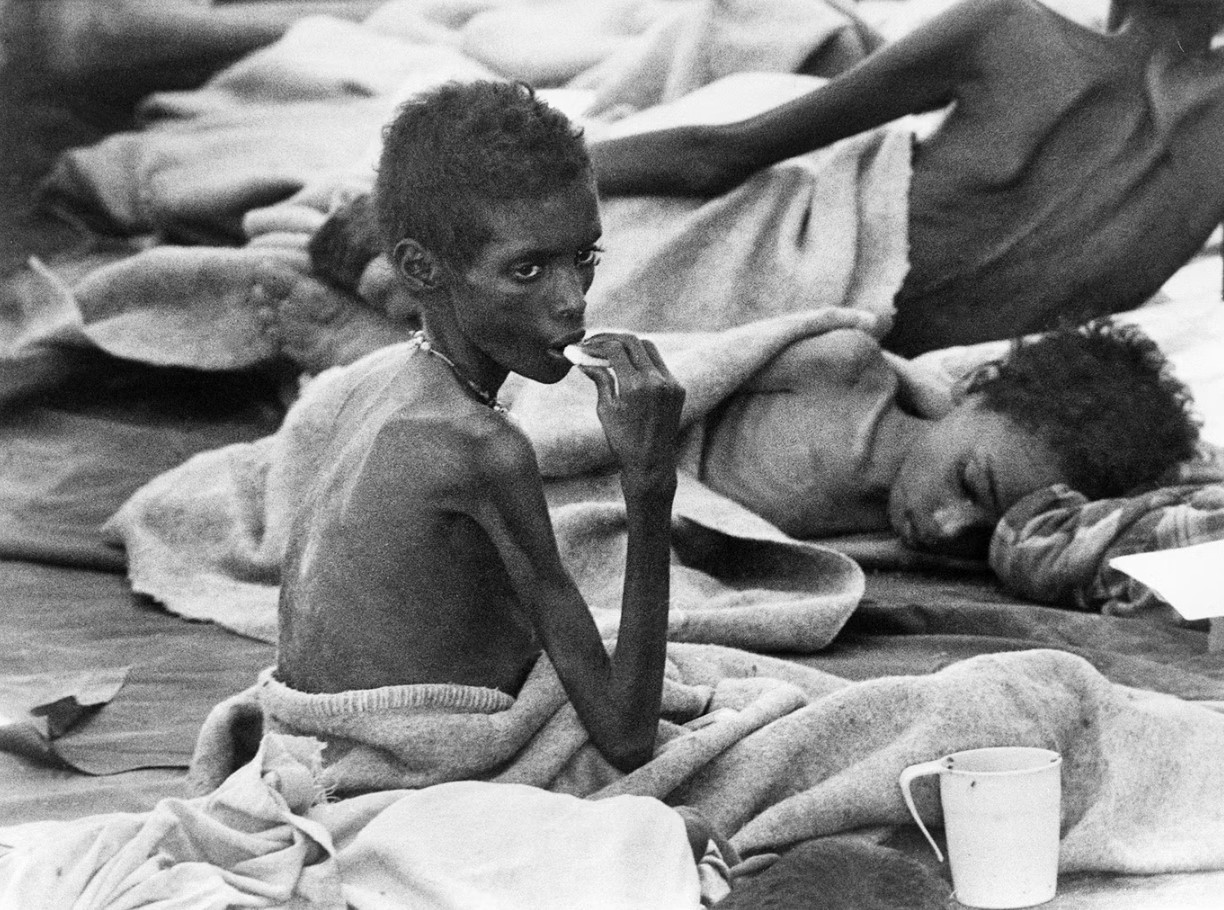

Unfolding within Tigray and several other regions of Ethiopia is a hunger crisis that many experts are likening to the beginning of the 1983–85 Ethiopian famine, which resulted in between 300,000 and 1,200,000 deaths.

Within the next 2 months, the majority of Tigray is expected to enter, if it has not already, IPC (Integrated Food Security Phase Classification) Phase 4 Emergency levels of hunger. IPC 5, one stage higher, is famine.

Consulting Batseba Seifu

Pertaining to the crisis, we spoke to Tigrayan activist Batseba Seifu, who was able to outline a number of key aspects of the ongoing crisis, what continues to happen, and what needs to be done in order to save lives.

Ms. Seifu holds a Masters of Public Administration in Public and International Non-Profit Management and Policy from New York University and a BA in Law and Justice. She has worked with a number of different Tigrayan activist groups and participated in several different campaigns to raise international awareness both on the famine, as well as sexual violence faced within Tigray and elsewhere in the world.

Currently, Ms. Seifu is heading a campaign through change.org to the UN, EU, UK, IGAD, the AU, and a number of different US Senators in an attempt to push for international demands that the government of Ethiopia recognize what many activists are claiming is an ongoing famine.

The link to this petition, where you can sign it as a means of rendering assistance, can be viewed here.

An Evolving Famine

The hunger crisis within Tigray is nothing new. Ongoing for years, the crisis is resultant of a number of different issues, which will be explored throughout this article, namely:

- War

- Foreign occupation

- Drought

- Insufficient aid

- Economic issues

- Government Ignorance

In addition, the details of the Pretoria Agreement, which ended the Tigray war, will be gone over.

War

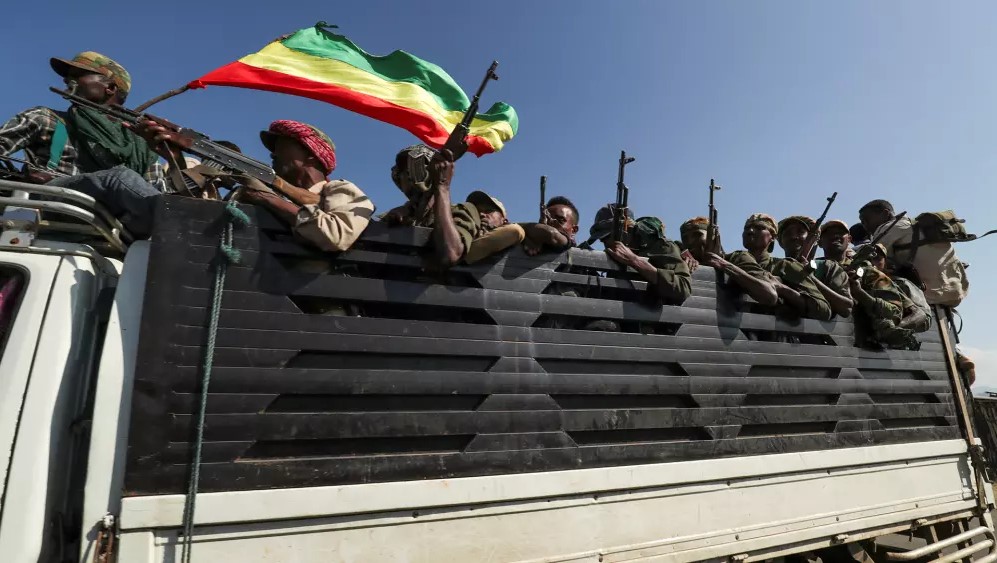

The present crisis in Tigray and other large portions of Ethiopia has arisen primarily from a series of conflicts over several decades. One such conflict is the ongoing war between Federal Ethiopian forces and Amhara regional forces.

The most notable war which decimated Tigray in particular, occurred from the 3rd of November 2020 to the 3rd of November 2022, ending after the signature of the Pretoria Agreement on November 2nd. The war began following years of political tension between the Tigray People’s Liberation Front, the Federal Ethiopian Government, and Eritrea.

Over the course of the war, which was largely concentrated in Tigray with small spillovers into neighboring regions, Tigray suffered extensive damage. The damage was not only to critical infrastructure (the capital city of Mekelle went a year and a half without power), but also notably to the region’s farmland and crop storage.

Approximately 75% of Tigray’s population are farmers. However, widespread looting and targeted destruction of Tigrayan farmland resulted in approximately 81% of small households losing their crop, 75% losing their livestock, and 48% losing their farming tools. Due to these losses and the fact that such a large portion of Tigray’s population is reliant on agriculture, unemployment skyrocketed.

At the same time, harvest yields plummeted as farmers across Tigray were prevented from farming by the opposing forces, while many others were displaced by the fighting.

During fighting, the Ethiopian and Eritrean governments both received accusations of using hunger as a weapon due to their specific targeting of farmlands and looting of food storage, and for a blockade both nations maintained in the region. While decimating its ability to sustain itself, the government allowed for a very minimal amount, if any, of humanitarian aid to come into Tigray. Sexual violence was also distinctly common over the course of the war, with both sides drawing accusations of using it as a war tactic against the opposing side.

Medical issues resulting both from widespread malnutrition and rapidly spreading disease were made worse by the fact that 90% of Tigray’s medical facilities were either damaged or destroyed during the conflict. Following the conflict, many of these sites still remain inoperable due to very slow reconstruction efforts as well as the limited delivery of medical aid.

USAID and the World Food Programme (WFP) have individually accused the Ethiopian government and allied regional forces, the Eritrean government, as well as the TPLF, of looting aid shipments.

Due to information blackouts instated by the Ethiopian government, it is difficult to determine an accurate number of casualties that came from the Tigray war. As such, civilian fatality estimates range from 160,000 to 600,000 people, of which several hundred thousand were from hunger.

All warring parties in the conflict have been accused of a number of different war crimes and crimes against humanity. However, despite the calls from both activists and the international community to hold the warring parties accountable, there have been no efforts to bring charges against those responsible.

The Pretoria Agreement

The Pretoria Agreement, signed on November 2nd, 2022, and in effect as of November 3rd, 2022, is responsible for the ending of the war in Tigray. While the agreement was successful at “silencing the guns,” Ms. Seifu highlighted for us a number of different ways the agreement has failed to be implemented, several of which contribute to the present crisis.

According to the agreement, the government is to have soldiers deployed along the “international boundaries” of Ethiopia, as well as to “safeguard the sovereignty, territorial integrity, and security of the country from foreign incursion.”

Despite this provision, however, Eritrean troops continue to occupy significant portions of Tigrayan territory. Eritrean forces regularly carried out attacks against civilians during the war. Their continued presence prevents the resettlement of displaced populations who had lived in the areas now occupied by a foreign entity.

The agreement also calls for Tigray to have representation in the federal government’s House of Federation, and the House of People’s Representatives. To date, this representation has yet to be implemented.

Additionally, the agreement calls for the government to facilitate the entrance of humanitarian aid into Tigray and participate in Tigray’s reconstruction. Humanitarian aid entering Tigray has oftentimes been bogged down by logistical issues and is also usually insufficient to tackle the true needs of the population.

In March of 2023, both the UN and the US temporarily halted aid deliveries to Tigray, citing the discovery of a “large-scale” plot in order to steal a mass amount of aid shipments nation-wide. Due to the security risks, USAID and the WFP halted their aid shipments as well. This halt was eventually extended to the entirety of Ethiopia, in which several regions face food insecurity, in June 2023.

A number of different humanitarian aid donors to Ethiopia have accused the Ethiopian government and military of being behind the plot, which Ethiopia has dismissed as propaganda.

Reconstruction efforts have also been notedly slow within Tigray. The damage that the region suffered during the war was extensive and was estimated to cost a total of 20 billion USD to repair.

Notably, at the same time, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has announced plans for Ethiopia to construct a new palace, which will cost 10 billion USD to build.

The Pretoria Agreement may be read in full here.

Foreign Occupation

While the war began between the forces of Tigray and the Ethiopian government, Eritrea and several other regional Ethiopian forces also joined the conflict. Namely, Amharas regional forces. Amhara, a neighboring region of Tigray, had long had a border dispute with Tigray, laying claim to a significant portion of Western Tigray. Notably, Western Tigray is some of Tigray’s most fertile land.

As the war went on, Amharas regional forces occupied the disputed territories and reportedly carried out a series of ethnic cleansing campaigns, forcing much of the Tigrayan populace out of the region. Amhara has claimed the region as their “ancestral homeland”.

Several regions of Western Tigray remain occupied by Amhara forces to this day. As previously mentioned, Amhara is currently embroiled in a conflict of its own with the central government.

Eritrea has a rather complicated history with Ethiopia, only gaining de facto independence from Ethiopia in 1991 after being annexed by Ethiopia under Emperor Haile Selassie. Following Eritrea’s official independence in 1993, tensions between Eritrea and Ethiopia were rather high, in particular during and after the 1998–2000 Ethiopian–Eritrean war. In the years following, border disputes were common.

With Abiy Ahmed’s premiership, relations between the two nations were largely restored; however, the border dispute remained. Following the war, Eritrea’s forces have remained occupying significant portions of Northern Tigray.

Notably, neither Amhara nor Eritrea were parties to the Pretoria agreement.

Approximately 40% of Tigray is presently occupied by both Amhara and Eritrea. Additionally, an estimated 1.4 million Tigrayans remain internally displaced, a year and a half after the wars ended. Many of those still displaced lived in the occupied areas and have been unable to return due to their continued occupation. The significant reduction in Tigray’s size, paired with the added stresses of hosting massive internally displaced persons (IDP) camps, has worsened the hunger crisis.

The East African Drought

For several years now, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia have been in a drought. The drought has worsened already bad conditions in war-stricken Somalia and Ethiopia and provided economic strain in Kenya, alongside food insecurity.

Within Tigray itself, the drought made the survivability of both crops and livestock even worse. For those that survived the attacks and looting, many fell to the drought.

Similarly, drought conditions within Tigray have stressed efforts to replant and rebuild livestock populations, further complicating efforts to combat the crisis internally.

Ethiopia’s government has announced it is delivering aid to those affected by the drought; however, minimal aid from the government has entered the region.

Over the last few months, amidst the drought, there have been simultaneous floods. Kenya, Somalia, Ethiopia, and Tanzania have all been witness to intense floods that have killed several hundred people and displaced hundreds of thousands.

The rainfall between the 2023 October and December “short rains” season was the most intense recorded in the last 40 years. The typical rainy seasons have been recorded as some of the areas driest in the last 40 years, with 2022’s rainy season marking the driest.

Worsening the drought has been the high presence of desert locusts for the past several seasons, contributing to decimating the remaining crop.

Insufficient Aid

As hunger continues to grow not just in Tigray but also in large portions of Ethiopia, one thing is apparent: there is simply not enough aid being delivered to Ethiopia.

There are a number of reasons for this. Namely, the resumption of aid has been slow, and the Ethiopian government has largely denied the existence of the crisis in the first place.

As previously stated, USAID and the WFP halted aid deliveries to Tigray last year in March, citing the discovery of a “large-scale” plot to steal aid nationwide. The halt was extended to the remainder of Ethiopia in June.

Humanitarian groups and activists were highly critical of the move, with many saying that USAID and the WFP could have taken other avenues in order to deliver aid rather than halting aid altogether, but simply chose not to.

Many of the humanitarian donors to Ethiopia accused the government and military of being behind the plot, an accusation the government has dismissed as “propaganda”.

In December, both USAID and the WFP lifted their halt on aid after having implemented a series of new security measures in order to prevent future potential theft. The rollout, however, has been rather slow. While they are slowly increasing the amount of aid each month that they deliver, it is, as stated, slowly.

Additionally, the Ethiopian government has made notable efforts to hide the ongoing crisis. Various government departments have made contradictory reports on the crisis, with some acknowledging in small part that there have been a limited number of “hunger-related deaths”.

Prime Minister Abiy has gone a step further, instead blaming deaths upon “malnutrition-related illnesses” rather than from hunger itself. PM Abiy and portions of the government have continually accused Tigrayan activists and regional authorities, who have been sounding alarm bells for several months on mounting hunger, of attempting to “politicize the crisis”.

Donor groups have mostly received their information on the crisis and the needs of the populace from the government. Many activists have accused the government of providing false data, which severely underscores the true severity of the crisis and the needs of the people.

As such, recent data suggests that only 15% of people who need aid are receiving it, leaving 85% without. As Ms. Seifu said, some aid is better than none, but the simple fact of the matter is that not enough aid is being delivered.

Within foreign-occupied areas, no aid is able to reach those affected by food shortages. The Tigrayan administration and aid groups simply cannot enter these areas to render any assistance, even if they had the aid supplies to do so.

In addition, both USAID and the WFP have both been accused by civilians of delivering soon-to-expire food aid. The practice was apparently stopped after it was found.

Economic Issues

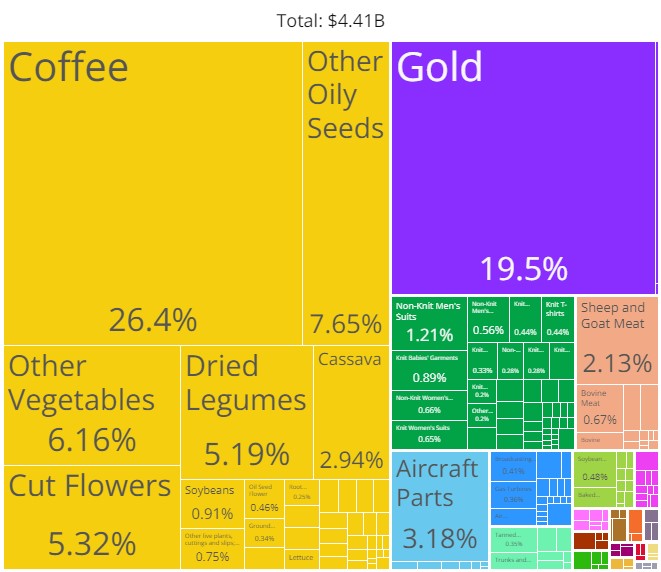

Though Ethiopia has in recent times been one of Africa’s fastest-growing economies, they still continue to face a number of economic issues that have harmed reconstruction efforts in conflict-affected areas as well as the standing of the people within these areas.

In Tigray, there are additional unique factors which worsen the economic issues even further.

Ethiopia’s economy is largely based upon agricultural industries, with coffee alone representing 26.4% of Ethiopia’s exports. Additionally, Ethiopia’s agriculture industry employs approximately 75% of the labor force.

These factors make Ethiopia’s economy very dependent upon global prices for agricultural products. Meaning, when products such as coffee experience a price drop, Ethiopia’s economy suffers.

The drought has weighed heavily on Ethiopia’s agricultural sector. Despite most of the populace being dependent on agriculture, only 5% of Ethiopia’s land is irrigated. In addition to this, improved seed, fertilizer, and pesticide use is not particularly common in Ethiopia’s agriculture industry.

Ethiopia has also faced particularly high levels of inflation over the past several years. In July of 2023, Ethiopia’s inflation rate was 28.8%, which was actually the lowest rate since July of 2021. Consumer good prices increased, while the purchasing power of both peoples currencies as well as products they could trade decreased.

Ethiopia has experienced high levels of inflation due to a number of factors, namely the internal conflicts, effects of COVID-19 (of which most, if not all, of the world suffered economically), the drought, as well as the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Prior to the Russo-Ukrainian war, Ukraine was Ethiopia’s top grain exporter. With the breakout of the war and the eventual breakdown of the grain deal between Russia and Ukraine (which had allowed Ukraine to still export large amounts of grain to various nations, Ethiopia included), Ethiopia has been forced to find other avenues to import grain. Because of this, Ethiopia’s economy and food supply have suffered.

Following the collapse of the grain deal, Russia promised to deliver free grain to six different African countries, which were concerned the failure of the deal could severely harm their food supplies. Ethiopia was not among these countries.

Within Tigray itself, as stated, there are a number of unique factors that contribute to the economic strain.

Over the course of the war, a significant portion of Tigray’s farms were damaged or destroyed. Given the amount of Tigrayans employed in the agriculture sector, unemployment skyrocketed during the war, with issues remaining pending reconstruction efforts. There are a number of documented cases of hostile forces purposefully sabotaging Tigrayan farms and ruining soil, further complicating efforts to restart Tigray’s agriculture.

With the hunger crisis unfolding following the start of the war, many Tigrayans were forced to either sell off their remaining seeds and livestock (those which were not looted, destroyed, or killed) or consume them themselves in order to survive. The availability of seed and livestock plummeted within Tigray.

The financial strain provided by the extreme harm suffered by Tigray’s agriculture industry, paired with the fact that civil servants within Tigray were, of course, not being paid by the government, meant there was little funds available for the average person. Rising market prices for seed and agriculture left most people simply unable to afford any meaningful amounts of food and agricultural products in order to supply their farms.

While the war is over, foreign occupation and stalled reconstruction efforts in Tigray have left 1.4 million people internally displaced. There is little economic opportunity for those displaced. Many Tigrayans, displaced or not, have been impoverished by the numerous crises facing Tigray over the last few years.

Government Ignorance

A reoccurring issue since the beginning of the crisis until now is that the government is largely ignoring the crisis.

For several months, regional authorities within Tigray have been sounding the alarm about both the level of hunger and the deaths it has been causing. The government has continually denied that there is any sort of problem and accused Tigrayan regional authorities and activists of attempting to “politicize the crisis”.

After continual denial of deaths by the government, Ethiopia’s national Ombudsman admitted to approximately 400 deaths by starvation over the last several months in Tigray and Amhara, the vast majority of which were in Tigray.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, however, denied the report by the Ombudsman.

“There are no people dying due to hunger in Ethiopia” -PM Ahmed, February 6th, 2024

PM Ahmed denied any deaths due to hunger, instead redirecting any apparent fatalities, saying that some people “may have died” due to malnutrition-related illnesses.

Again, in contrast to PM Ahmed’s words, are those of a group of Ethiopia’s Members of Parliament’s Foreign Relations and Peace Affairs committee. A small group of MP’s paid a visit to Tigray last week, and some of the MP’s have spoken rare words of concern for Tigray.

“We saw people in dire situations that can hardly be described as living” -Moga Ababulgu, Member of the Foreign Relation and Peace Affairs Standing Committee

The MP’s visit centered around Mekelle and surrounding areas. Mekelle is, according to the IPC ratings established by the United States’ Famine Early Warning System, one of the more secure regions of Tigray. Despite this, the situation within Mekelle is still dire. Mekelle is host to approximately 185,000 internally displaced people (IDP). According to Mekelle’s deputy mayor, Elias Kassaye, the camp of IDPs has not received food assistance in over 10 months, coinciding with around the time the halt in aid was implemented by USAID and the WFP.

According to Dima Negewo, “the devastation in Tigray is the result of a chain of catastrophic man-made and natural phenomena.” Additionally, remarks made by the visiting MP’s included the admission that foreign occupation of Tigrayan land was further complicating relief efforts.

“We have visited drought-affected areas. The people are suffering not only from a shortage of food, but also water. The convergence of these problems is heavily impacting society, resulting in the deaths of domestic animals and the withering of plants” -Dima Negewo

Activists and certain Tigrayan political figures have additionally accused the Ombudsman of still underreporting numbers. While there are no certain figures on fatalities resultant of the famine, the president of the Tigray Interim Regional Administration, Getachew Reda, has stated that “thousands” of Tigrayans have died from starvation in the last few months.

Statement on the unfolding famine in Tigray pic.twitter.com/vZrlfz8CqL

— Getachew K Reda (@reda_getachew) December 29, 2023

Additionally, Reda claims that 91% of Tigray’s population has been “exposed to the risk of starvation and death”. He further adds that the resources available to the regional administration are nowhere near what is required to properly address the crisis. While the regional authority has requested assistance from the government, any assistance rendered has not been enough to make any feasible difference.

Reda further likened, as have a number of other activists and experts, the situation to the beginning of the 1983–85 famine. When being interviewed on the visit by Ethiopian media company The Reporter, they were questioned about this claim and whether they too, would liken what they had seen to the famine. The parliamentarians responded that the length of their visit, just three days, was not enough to properly get a grasp on the entirety of what is happening within Tigray. While the MP’s words do not serve as an outright denial of these claims of similarity to 1983, claims the government has repeatedly opposed, they also do not serve as a confirmation of these claims.

The MP’s visit to Tigray serves as the first time that federal MP’s have voiced major concerns over the situation within Tigray since the end of the war. While the MP’s statements on the matter leave much to be desired, the visit is certainly a step in the right direction.

What Needs to be Done: Calls to the International Community

Since the beginning of the war and after, several different international entities have had a stake in both the conflict and the crisis as a whole. The UN, the EU, the AU, the US, IGAD (the Intergovernmental Authority on Development, an east-African economic bloc of which Ethiopia is a member), and several more nations and organizations each had a stake in the conflict, some of which had a stake in its aftermath as well.

While the UN of course has their part on the world stage and attempts to bring about justice, the group with perhaps the most important role in the near future and the greatest capacity to bring about change is the African Union (AU).

As Ms. Seifu said, the AU not only has the advantage of being a regional body but also of being the ones who negotiated and instituted the Pretoria Agreement. As such, the AU has the responsibility to see that the Pretoria Agreement is upheld and implemented properly. However, as previously discussed, it is not being implemented properly, and thus the AU faces several obstacles ahead.

Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, is a primary center for the AU. Because of this and Ethiopia’s historical political influence, the government of Ethiopia maintains a significant amount of influence within the AU. Seeing as the Ethiopian government has largely been resisting any meaningful attempts at mitigating the crisis, this poses a significant problem for whether or not the AU will actually attempt to exert any pressure upon Ethiopia to bring about change.

A secondary issue remains Eritrea. While Eritrea is an AU member, they were not a party to the Pretoria Agreement. As such, Eritrea remains an occupier in a significant amount of Tigray’s territory.

Eritrea is a particularly unique state. They are extremely isolationist, largely resistant to outside pressure, and internally already have an abysmal human rights record. While they are resistant to outside pressure, they are not immune to it. The AU remains the organization with the greatest capacity to exert pressure upon Eritrea to end its occupation of Tigrayan lands, an occupation that is preventing any aid from reaching those still within occupied zones.

Eritrea has a rather troubled relationship with the West. They’ve refused any western aid, with Eritrean leader Isaias Afwerki insisting that western aid to Africa is intended to cripple it. Because of this, the West is largely unable to put any meaningful pressure on Eritrea beyond the sanctions already in place.

Notably, the West seems to be growing increasingly unwilling to put the necessary pressure on the Ethiopian government to bring about required change. While during and shortly following the war there was capacity for bringing about change and even the potential pursuance of justice for crimes committed during the war, in the last several months a number of western governments, the EU included, have shown signs of again normalizing relations with Ethiopia. These western nations and groups have begun reinstating monetary aid programs, such as a $680 million USD aid package that was promised by the EU in October of 2023 to Ethiopia, a package which was originally delayed because of the Tigray war.

When it comes to criticism from Tigrayan activists to the greater international community, there are, of course, many. Among the forefront of which, is the complete implementation of the Pretoria agreement.

While it cannot solve all of the problems facing Tigray, it can assist in mitigating the most severe. Ending foreign occupation, allowing increased aid, and affording Tigray the political representation guaranteed to them by both the Ethiopian Constitution and the Pretoria Agreement are key to addressing several problems directly. These include saving lives, increasing Tigray’s ability to combat the other issues it faces, such as combating the effects of the drought, and increasing reconstruction efforts.

As mentioned before, the claimed faulty data put forward by the Ethiopian government and the prevalent denial of the issue at hand are also substantial. Activists seek to receive data pertaining to the crisis from regional authorities who have been sounding alarms for months, not from the federal government, which has continually denied the problem.

In regards to the Ethiopian government, they can be subject to foreign political pressure in order to not only acknowledge the famine but also to assist in lessening its effects. In contrast to Eritrea, Ethiopia maintains a significant relationship with the West and could be subject to pressure if those nations choose to exert it.

The West and the United Nations also maintain the capacity to push for a level of justice for crimes not only that were committed during the war but also that continue to be committed, particularly in occupied areas (where attacks, sexual abuse, and kidnappings remain fairly commonplace).

Different international actors have different capacities to address different portions of the conflict and famine. As such, a collective and unified approach between these different bodies, one which prioritizes justice, is necessary to ensure a full end to the crisis.

When it comes to aid, activists have called for a “targeted intervention”. There are a number of areas that are most in need and thus should be addressed first. Namely, aid should first and foremost be provided to those who are on the verge of death in all of Ethiopia.

A Conclusion and Hopes for the Future

As stated at the beginning of this article, the world holds within it no shortage of human suffering. The overwhelming majority of which is not reported on or spoken about nearly as much as it should be. In recent times, the world has witnessed countless atrocities, something that, despite the world’s stated goal of “never again”, happens again and again.

In the age of information, it is all of our responsibility to utilize the tools at our disposal, stay informed of the world’s happenings, and ensure that no community is forgotten about. While Tigray was discussed in this article, there are countless examples of regions that are not covered with the urgency they should be.

Regardless, the future of Tigray is uncertain. If things continue on their current path, with insufficient aid and government denial, the future for Tigray looks to be one of heartbreak, starvation, and death. But it does not have to be this way if the international community is able to come together and take concrete action to prevent tragedy from striking yet again.

The story of Tigray, and Ethiopia, is a long and complicated one. Much of it was not explored within this article, but it is one worth telling, and most certainly one worth continuing.